There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

David Foster Wallace, in 2005 Commencement Address to Kenyon College

There is a funny thing I’ve noticed about telling that David Foster Wallace story: I am convinced at this point that everyone who hears it imagines themselves as the older fish.

Especially investment professionals who hear the story.

Don’t get me wrong. If there is one thing more ironic than believing you are the older fish in the David Foster Wallace story, it is telling the story in the first place (since the moral of the story is that humans are all wired to be the two younger fish). And if there is one thing more ironic than telling the story in the first place, it is doing so and then immediately teasing others for not understanding the moral of the story. As chief among us sinners, therefore, I will tell you what I think and what I think I know.

Like Ben, I think the water is changing. I think several ‘immutable’, ‘inherent’ features of financial markets are being recognized as stories subject to revision. I think missionaries with a vested interest in those stories are actively working to promote their preferred Narrative as something the crowd believes the crowd believes. I think such a change in any one of five such stories is important enough alone to change the way we allocate capital, develop investment strategies, structure markets and conduct business as investment professionals.

I think these are those five stories. I know that there are certainly more that don’t occur to me because, well, that’s the nature of the water in which we swim.

- We live in a deflationary world.

- We live in a flat world.

- We live in a world in which the Fed has your back.

- We live in a world in which doing anything other than maximizing top-line growth is value–destructive.

- We live in a world of easy credit, abundant leverage, inexhaustible liquidity and limited regulatory scrutiny.

Now let me tell you what I don’t know.

I don’t know how to predict how and when the old narrative will die. I don’t know how to predict when the new narrative that replaces it will be born.

Oh, I have some ideas.

But first you deserve to know why someone willing to tell you he thinks the water is changing went all soggy when it came to giving you any details about how we will know that it has changed.

I’m not expecting it. I’m observing it.

George Soros

Yeah, yeah, we use this Soros quote a lot. Why are you booing? He’s right.

Still, there are limits to how far observation can get us. It is true that if we were content with perfunctory, nearly tautological answers to how zeitgeist-defining narratives like the five I mentioned above are born and how they die, well, that would be no problem at all. They are born when enough people believe that everyone else believes in them. They die when the opposite happens. Not when enough “facts” about “reality” accumulate, except to the extent the crowd believes those are the things that will change everyone’s mind. And certainly not when an older fish comes along to let everyone know the “truth” about them, which never changes anyone’s mind.

On its face, however, that explanation isn’t very useful. We can just sit here agreeing with each other until we are blue in the face that it feels like COVID killed collective belief in “The World is Flat!” stone dead, but it doesn’t get us any closer to being able to measure something as abstract as ‘what the crowd believes the crowd believes’. What we call The Narrative Machine, our research effort here at Epsilon Theory, is an attempt to represent that abstract concept – something game theory calls Common Knowledge – through a model. Since we can’t measure what the crowd believes directly, we instead observe the behavior by influential individuals and institutions (e.g. politicians, executives, celebrities, core cultural institutions, Wall Street, Madison Avenue and the media). More specifically, we observe their Missionary behavior, by which we mean linguistic evidence of attempts to shape, create and sustain those narratives.

Oceania had always been at war with Eastasia, that kind of thing.

And then we measure it.

Now, the Narrative Machine is not a model for what the crowd actually believes about some topic. For reasons we have written about at length previously, we don’t think that would be very useful anyway. Instead, ours is a model which seeks to represent what the crowd believes the crowd believes, which as we see it is a lot closer to the transmission mechanism for a market populated by real, thinking people – and the machines they code to exploit the same. It is based on the idea that sufficiently widespread and shared use of distinctive phrases closely related to a topic (e.g. Auto stocks), framing (e.g. “Auto stocks are really a bet for or against EVs”) or premise (e.g. “investors are bullish about Tesla’s capacity growth”) is strongly indicative of the presence of common knowledge. In other words, we believe there are important publications and people that the crowd will assume others will have heard. You don’t trade above-the-fold of the Journal, but before you sit down at your terminal, you’re pretty sure everyone you will talk to that morning has at least glanced at the headlines. You don’t build political strategy around the, uh, thoughtful arguments put forth on the opinion page of the Washington Post, but you damn sure operate knowing that the staffers across the hall have read it.

When we observe those publications and people telling the crowd what the crowd thinks, and when we observe other publications and people begin to use that same language to describe what the crowd thinks about a topic, framing or premise, we think those observations are generally really good models for what we would observe and measure if we could observe and measure common knowledge itself.

As it happens, we think there are good and reasonable behavioral grounds for this approach, too. Humans tend to be optimistic about their own ability to resist being told how to think and very pessimistic about the capacity for other humans to do the same. If a publication or celebrity begins telling us how to think, we certainly wouldn’t let that affect us, but we are more than happy to believe that it shapes the beliefs of others. More importantly, we think civilizations are built on foundations of memes – images, stories and connotations that have repeatedly demonstrated the ability to survive and reproduce when attached to contemporary events. Manipulation of the masses through media is Lindy, I suppose. All of which increases our confidence that measurable missionary behaviors are a reasonable model for what the crowd believes the crowd believes.

But a reasonable model isn’t a perfect one.

The biggest problem with this model presents itself when we aren’t talking about bull case narratives for Tesla or a “time to rotate to cyclicals!” narrative being pushed by some sell side house with an axe. That kind of thing we can observe in all of its useless, cringeworthy glory, for all the good it does us. The problem is the zeitgeist-defining narrative that is so fundamental to our understanding of what stocks and markets and companies and capitalism ARE that it isn’t even discussed.

After all, fish don’t swim around talking about the water.

What I mean is that it isn’t as if moral missionaries host urgent press conferences to shout from the lectern, “Most Americans think that murder is wrong!” Neither does the Wall Street Journal daily voice things like, “institutional investors don’t seriously consider inflation” nor Barron’s that “everyone still believes in a Fed put” nor the CIOs of the ten largest institutional asset owners in America that “free and fair trade is still the path to collective global prosperity.”

The Narrative Machine, whether we mean Epsilon Theory’s models or the brains that you and I have tried to train to consume information more judiciously, is good at measuring missionary activity and narrative adherence. That is, we can see when efforts are being devoted toward telling us what to think. Once we spot those, we can see when people or outlets are staying very on-message or going off-script. Think of missionary activity and narrative adherence as the currents and temperature, if you’re not sick of nautical analogies yet.

The five stories I mentioned above, and a hundred others to which we rarely give a second thought – THOSE are the water in which we swim as investors. They reflect our implicit belief in collective stories that no longer require observable missionary behavior because they are already fully integrated into our institutions, laws and conventions. We don’t have to talk about them very much any more. We don’t need missionary nudges to believe that the crowd believes in them. And changing them is like trying to free a 220,000 gross tonnage container ship that has wedged itself in the silty sides of a canal.

Last tortured nautical analogy, I swear.

Because it is so hard and because it is assumed to be impossible, the implications of a true change in the water, of a shift in a zeitgeist-defining narrative, are monumental. If the common knowledge about something like inflation or globalization changes, it changes everything. And yet, missionaries on Wall Street telling us that it is time to consider acting on ‘active tactical and opportunistic fixed income products with a flexible mandate’ isn’t evidence of a change in common knowledge about inflation. Neither is table-pounding from a key politician about a ‘balanced budget’, if such a thing is even conceivable in 2021. Nor is a data point or two dozen data points indicative of reflation, deflation or anything else. Not even an Epsilon Theory note or two about the topic.

Which leads us to a simple, if unsatisfying truth:

A model which uses missionary behaviors as a proxy for common knowledge isn’t enough to observe what is happening to the water in which we swim, much less to reliably predict when it is changing.

There is hope.

We have a lot of data we can work with. But data isn’t information. Information is what causes someone to change their mind. And if we want to know what will cause the crowd to change its mind about the water in which it swims, I think that we also must get in the habit of asking a different question – a question that is at once a fundamental query of both information theory and game theory.

What do we need to be true?

Imagine that you are a famous and wealthy financier. Let’s say that your name is, oh I don’t know, Schlex Schreensill. Now let us say that you are being investigated for fraud. You’re in an interrogation room, and you know that a politician involved in facilitating your maybe-not-entirely-above-board financial scheme is in the next interrogation room over. He knows enough to be dangerous, and his hands are dirty, too. He might even be a bigger target.

The investigators have enough to issue you a nominal fine for “failure to supervise” or something already, and to smear the politician in the court of public opinion. You’re both almost certainly going to get a slap on the wrist, but then again, maybe you can convince them it was the other guy all along and skate on all charges. To throw either one of you in jail, however, they need one or both of you to talk. So begins a process of Good Cop / Bad Cop, of carrots offered to get you to rat out the politician and of sticks threatened if you don’t. And remember, he’s a politician, so of course he’s going to take any opportunity to rat you out, which the agents are very happy to remind you.

A good, old fashioned Prisoner’s Dilemma.

Now, in the classic case of this game theory problem, the equilibrium outcome – the outcome that it’s impossible to reason your way out of once you’ve really thought through what the other guy must be thinking – is that both you and the politician rat each other out. In the end, the cost of being made the sucker is just too high to believe the politician will be willing to risk it. Besides, a reduced sentence for cooperation is still prison, but it’s better than the alternative.

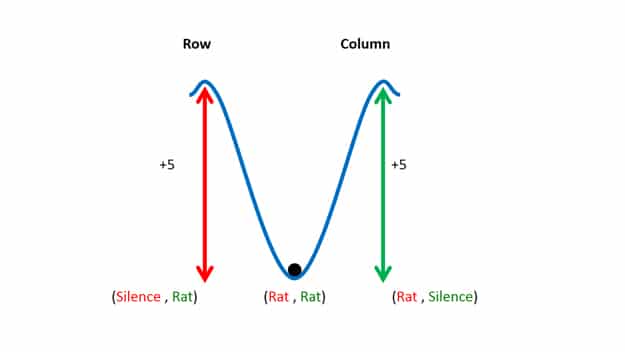

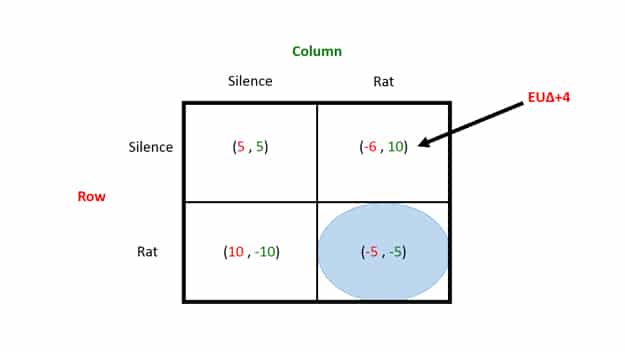

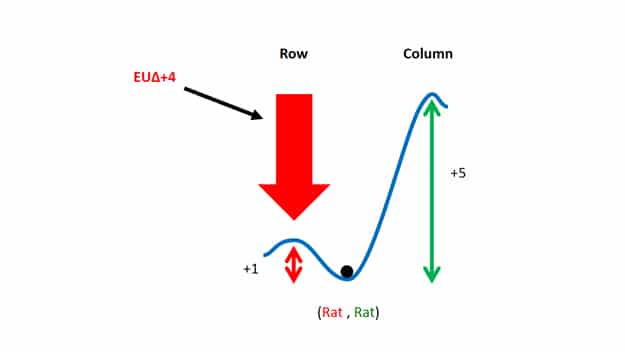

As Ben wrote about some years ago in a now-classic Epsilon Theory piece, it is both possible and useful to think about this in information theory terms as well. The idea of the illustration below is to represent the depth and symmetry of the equilibrium state of the game. It represents the amount of informational content that would be necessary to change the conditional payoffs of the game and for the “ball” to roll to a new equilibrium.

Ben’s example asks the reader to consider how this “information surface” would change if one of the payoffs changed. In this case, that change is a material reduction in the cost to Schlex of keeping mum.

To be sure, mutual defection is still this game’s equilibrium. The politician grinds his teeth, but just can’t bring himself to believe that you’d be willing to risk even one extra year in prison if he plays ball with the cops and you don’t. But he is grinding his teeth. This equilibrium is NOT as strong as the equilibrium of the classic game. Only a small amount of information about payoffs, about predispositions of the other player, the conditions which might cause a change in those payoffs, the expectation of repeated play and/or the uncertainty attached to all of the above would be necessary to move the ball out of that equilibrium.

What does that have to do with narrative structure?

In the case of most narratives and missionary activity we track, we generally observe an information surface with pretty short walls. In other words, when the WSJ writes about how analysts perceived an earnings update, or when ESPN writes about how baseball fans are responding to a decision to move the All-Star Game in response to a new voting rights law in Georgia, it immediately changes common knowledge. The amount of information that it takes to change what the crowd believes the crowd believes is pretty small. If you can observe that language repeating itself and attaching itself to a widening set of topics and sources, you are observing a change in the equilibrium.

In the case of zeitgeist-defining narratives, the water in which we swim, the walls of the information surface are often insurmountably steep. What I mean is that it doesn’t matter how many missionaries tell you that everyone thinks that globalization should reverse or will reverse, or which person or publication said so. It doesn’t matter how many missionaries inform you that the 40-year bond rally is finally over and inflation is finally arriving as a risk, or which person or publication said so. Or at least, it doesn’t matter very much.

The walls which protect the equilibrium of the water in which we swim from new information are high.

And those walls are built out of the things we need to be true.

So what do we mean by the things we need to be true?

Let us start from the anecdotal and specific, and then pull back to something more general. Consider, first, the zeitgeist-defining narrative that “We live in a deflationary world.” Now consider a range of social structures or social structure-defining conventions that have been assembled around that narrative:

- Practically every institutional asset pool of any size in the United States has a formal investment policy statement which requires a 20-40% allocation to nominal bonds;

- Perhaps half of the fees charged to individual investors by the financial services industry are functionally paid only for professional advice about how much of an allocation to nominal bonds should be added to a portfolio of equities;

- Retail investment products with access to inflation-sensitive assets are sparse, hypothetical, poorly constructed, and largely focused on asset classes with equity-like and growth characteristics that could still be sold to clients during a deflationary period;

- Benchmarks, indices and conventions for reporting and measurement are built around a balanced allocation to stocks and nominal bonds;

- Securities exams, university curricula, textbooks, personal finance books, internet guides and encyclopedias explicitly frame nominal bonds as a (1) risk-free or low risk asset and (2) an equity-diversifying asset; and

- US companies and their executives have been rewarded for four decades for creating (1) asset portfolios, (2) business models, (3) capital structures, (4) human capital, (5) product lineups, (6) brand and marketing profiles and (7) cost structures which emphasized the generation of top-line earnings growth in an environment in which cost inflation and pricing power were tertiary considerations, at best.

These conventions can change, of course. If the world truly enters a sustained reflationary / inflationary period, they will change. But until that happens, these will continue to act as high walls against a change in common knowledge, as container ships stuck in sludge.

Why?

Because, for example, if you are a major asset owner, law, policy and sticky investment policy statements will make it nearly impossible for your behavior to reflect a belief in a change in the inflationary / deflationary regime. And because you know that about yourself (and likely think your institution the more sophisticated), these embedded conventions will create a strong belief that the crowd doesn’t really believe in a change in the zeitgeist enough to change their behaviors. Add in the effect of legal conventions that create a positive obligation not to veer too far from common knowledge about ‘what is prudent’, and the threshold restricting expressions of a true belief in inflation that goes beyond the lip service of some floppy 2% allocation to a new ‘opportunistic real assets’ bucket is practically insurmountable.

Those who cannot change need the status quo narrative to be true.

The same goes for companies and executives, who have succeeded in a decades-long crusade to have options and restricted stock grants considered ‘aligned incentives’, a veritable coup that permits them to seek out short-term price appreciation over long-term value creation and have it, too, called ‘prudence’. Having been trained for more than a decade that cost of capital doesn’t matter, that cost structure doesn’t matter and that top-line growth is the only thing that does, an executive who pivots too quickly to restructuring to prepare for costs and pricing that matter will believe they are leaving money on the table. More importantly, they believe others will come to the same conclusion.

Those who have built their compensation models around a narrative need it to be true.

That old Upton Sinclair quotation about a man and his salary is true at a scale a lot greater than a single man. To be fair, the things we need to be true are not always so tangible. For example, ‘the world is flat‘ as a narrative is deeply entangled with the norm-enforcing memes that underpin all sorts of policy. A shift away from globalization would reflect implicit racism. A shift away from globalization would be a rejection of capitalism and free markets. A shift away from globalization is an expression of opposition to the democracy, freedom and peace that inevitably comes with open commercial relations. You may believe all or none of those memes – they’re not all meant for you or me, after all – but that doesn’t matter.

Those who have engineered permanent political polarization from a narrative need it to be true.

So how do we make this less specific and more general? How do we use it to help us consume information more effectively? I think that asking ‘what do we need to be true’ means asking at least these questions about any zeitgeist-defining narrative that we think may be in flux:

- High-friction Conventions: Has swimming in the water of this zeitgeist-defining narrative caused the emergence or creation of conventions, laws or ‘best practices’ which have significant frictional / switching costs – more importantly, is the crowd mutually aware of these high frictional costs?

- Gatekeepers and Offloaded Risks: Are there industries, lobbies, parties or special interests which have emerged because of and which are ultimately dependent on this zeitgeist-defining narrative? Are they powerful enough to make us skeptical that the crowd will change its mind?

- Entangled Memes: Are there powerful cultural or moral entanglements that make it difficult for the crowd to believe that the crowd will change its mind?

We think a model that explores common knowledge through the analysis of missionary statements – people telling us what the crowd believes – remains extremely useful. But only when there are not structural barriers to the crowd changing its mind. If we want to have any hope of knowing with any measure of certainty when the water has changed, much less predicting its outcomes, we must also observe what the crowd believes the crowd needs to be true.

We are already beginning our efforts to model this for our Epsilon Theory Professional and consulting clients. A lot of what we discover will make its way (and has made its way) into our regular publishing as well.

But for all of us, subscriber or not, wondering whether the water that has defined our investing, business and political careers is changing, it is time to get in the habit of asking a new question any time we consume information:

Well done, Rusty, really well done!

So much of who we think we are - who we want, nay, need to be - is wrapped up in the stories we tell ourselves about what needs to be true.

I am reminded of a line in the Falcon and the Winter Soldier where Bucky and Sam are talking. Sam is questioning whether Cap was right in believing in him. Bucky tells Sam that he can’t think that way. Because if Cap was wrong about Sam, then he was wrong about Bucky and that is something that Bucky can not live with. So he needs Cap to be right about Sam. Incredibly powerful moment.

Water indeed. Well done.

I’ll pile on one last nautical analogy that I think helps me to frame what you’re talking about.

This isn’t looking at descrbing the water in which we swim. It’s looking at how the water can change such that we have to adapt a new form of swimming. Quickly. Before we drown in the changing waters. How long can you swim the same way before you have to alter course because what you’re doing just isn’t working.

Man, this is like one of the two big philosophical/existential questions along with “How do you fight the monster without becoming the monster?” How shaky are the fundmental truths that you’ve built the most basic building blocks of your day on? How little has to change before those fall apart? As Rusty mentions, ther’s a ton of friction because of how much is entangled and tied up in a system that needs to work one way. But eventually, you’ve gotta go with the water.

“What do we need to be true?”

I’m pretty sure this is the driving force behind every story humanity has ever told.

Brilliant article! I will be meditating on the implications of this framing for a while.

Others have called this the “truth-shaped hole.” Unspoken assumptions that the writer/messenger/Missionary doesn’t mention encircle a gap in the picture - that itself becomes a picture once you have enough of the data around it.

Ugh, is there an “edit” button? I meant to say “leaves a gap in the picture” or “leave an outline that encircles a gap.” Either one of those makes sense.

Very thought provoking Rusty , it got me thinking ? - you know who needs the deflation narrative to exist - the U S Government, with that 30 trillion dollar anvil hanging around its neck an increase in rates that would occur if the real inflation rate was known would put it out of business. At least as we know it today.

That is why no matter how high inflation really goes I believe the CPI and other measures will be manipulated to show 1-2%. With hedonic adjustments they can basically make it say whatever they want. The bond market might balk but they will print enough to make sure that never happens for long. That lie will be protected to the end.

Very well expressed.

Because we are fish and not birds. We can’t evolve fast enough to keep up with the changes in the water.

frog in boiling water. it will be too late.

The currency (US $) would be the logical pressure relief valve to the hedonically adjusted, mis-measured CPI and the QE to handle the epic deficits. But (and I hate when Economists throw in “on the other hand”), the dollar is the reserve currency and it historically catches quite a bid when anything in the connected global financial brew turns sour. Our current account and budget deficits should change that narrative, but the narrative hasn’t tainted that water…yet. The dollar failing to rally in the next legitimate risk-off environment would be enough to flip that switch. Voila, we would have inflation that the Fed won’t stop. I didn’t say, “can’t stop”, the politics of tightening financial conditions when well below full employment will be avoided for long enough to get them way behind the curve.