This is Water

To learn more about Epsilon Theory and be notified when we release new content sign up here. You’ll receive an email every week and your information will never be shared with anyone else.

Continue the discussion at the Epsilon Theory Forum

6 more replies

The Latest From Epsilon Theory

This commentary is being provided to you as general information only and should not be taken as investment advice. The opinions expressed in these materials represent the personal views of the author(s). It is not investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. Any action that you take as a result of information contained in this document is ultimately your responsibility. Epsilon Theory will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information. Consult your investment advisor before making any investment decisions. It must be noted, that no one can accurately predict the future of the market with certainty or guarantee future investment performance. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

Statements in this communication are forward-looking statements. The forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date of this publication. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Epsilon Theory disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein. This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. This commentary has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. Epsilon Theory recommends that investors independently evaluate particular investments and strategies, and encourages investors to seek the advice of a financial advisor. The appropriateness of a particular investment or strategy will depend on an investor’s individual circumstances and objectives.

This post reminded me of two oldies but goodies and how important it is to call things by their proper name (“The Name of the Rose”) and the problems that arise when words mean something different to different groups of people (“The Market of Babel”).

The insidious effect of financialization has been that it has changed the Common Knowledge/Convention of words like earnings and capitalism, which I think is one of Ben’s points.

Pre-GFC “earnings” does not mean the same thing as post-GFC “earnings” even though we use the same word to describe both.

A millennial who only knows a world of easy money, record stock buybacks, and exorbitant CEO compensation will have a completely different meaning of capitalism than a Baby Boomer or Gen Xer.

This difference in language creates a “problem of meaning” where the observed “facts” of the world actually mean something different particularly between generations.

It’s why we are seeing a shift away from “capitalism” towards something else.

It’s why we are experiencing a widening gyre.

To recognize this change in language is to see with Clear Eyes.

This is a really interesting. “Financialisation” (sorry, UK spelling this time guys) is really where the gains of financial engineering outweigh the gains of real engineering, or to put it differently, the incremental gains on the bottom line of manipulating your capital structure is higher than the gains of actual investment in your core operations.

The ever-declining interest rates are a key cause in this because higher cost of capital will necessarily force companies into productivity-enhancing investment. Zero cost of debt capital means that companies do not have such high costs of capital that they need to reinvest their profits. Even talking about “cost of capital” like it is a real thing other than what investors want as a return by applying some half-baked financial model is an example of where financialisation creeps into our subconscious so much that we can only express ideas using financial language.

Financialisation though is reaching a point of over-engineering. Banks employ teams of high quality bankers who provide “credit rating advise” to their clients. That is, bankers literally approach clients pitching them to create a capital structure that “targets” credit ratings to improve their EPS or whatever metric management compensation is based upon. Targeting credit ratings is getting things arse-backwards: credit ratings should be the outcome of a process and not the end-goal in itself.

This over-engineering of the corporate world only means one thing: central banks will increasingly get concerned that higher rates will tip everything over. I am not a natural pessimist but given one reason why the Fed did not increase interest rates is because of the amount of sub-investment grade debt out there, one can only wonder how long the tail can wag the dog…

Ben-Great points as always! One would have thought that the Panic of 2008 represented the terminus of financial gaming and gimmickry, a welcomed death knell for what had become the complete “financialization” of the US economy, but noooo. Instead the Fed created conditions to double down on it. So, we have a economy that is even more hollowed-out drifting ever further toward the “7-11 Economy” I observed in Louisiana 30 years ago…now a Dunkin’ Donuts (empty, produce nothing entity on every corner…like 7-11s) economy.

I’ll be curious which side/faction of the “Political Utility” crowd wins…the side that relies on an ever-rising/ebulent stock markets to paper over societal under-saving/over-spending and the side that is clamoring for ESG companies/investment. Notice how companies are tripping over themselves in their craven attempts to be “ESG Friendly” so that they can be included in ESG indices…and ESG ETFs by extension. Eventually, everyone will be “ESG”…putting everyone in the index. Both lines of Political Utility thinking (two side of same coin like chivalry and chauvinism, kinda sorta don’t get one without the other) are antithetical to growth/progress when other economies/countries are less constrained by “fairness” (a flavor of the same ESG ice cream). Phil Gramm nailed it in yesterday’s WSJ Opinion piece. Enjoy! https://www.wsj.com/articles/enemies-of-the-economic-enlightenment-11555366746?shareToken=stcc6780d473a4439aa0f12f324268023b&reflink=article_email_share

Haul-ass, bypass, and re-gas!

The ESG cartoon has rapidly become my favorite cartoon.

It is an incredible case study in how quickly Wall Street and the financial services industry more generally are able to take an abstract concept, identify the “value” to be harvested, and then quickly productize strategies for strip mining that value.

Great article. I have been talking about this idea of financialization with not nearly as much clarity, finesse or the right verbage for awhile, but most people look at me like I am high. Like I don’t “get it”, particularly Wall Street. So I really appreciate how well you explain and address the subject.

The real tragedy of ESG, in my opinion, is that retail investors have now been taught that buying stocks based on their own personal ESG passion will not only advance their cause but is also a “smart” investment. Seeing all these Robinhood accounts pile into TSLA on the basis of supporting a green business while institutions and the BoD sell like crazy makes me sick to my stomach.

Agree. This seems like a relatively obvious con. And yet.

Surely some of the post-GFC “earnings” growth is due to Labor’s declining share of income?

Only if you are my age (54), or older, do you remember a time when it was hard to raise money for an investment. I know, today you still have to work to convince investors to put money into your idea (fund, IPO, start-up, mom-and-pop biz, new building, etc.) - but you know the money is “out there” (it’s like water to the fish, you don’t even consider that it isn’t there / you don’t know a time when it wasn’t there).

But there was a time when you simply couldn’t find capital for your great investment idea as it wasn’t there (there was no water). That imposed a discipline on how capital was spent because it was scarce and expensive. You couldn’t afford to lever-up your balance sheet - you needed to find a real idea to make real money (per Ben, by way of productivity improvement via new plant, equipment or technology).

I would never have guessed, ahead of time, that cheap capital would defeat real investing (it always felt like there were more good ideas than money in those days). But as Ben illustrates, cheap capital (via the CBs) has led to the financialization of the economy making it easier and smarter to leverage your balance sheet and legally manipulate your earnings than risking capital on an unproven investment. That is not an intuitive idea to someone who grew up in an era of tight(er) money and investment ideas desperately fighting for scarce and expensive capital.

And the other thing I remember - things failed, all the time. Many banks, businesses, factories failed / shutdown / closed. In the late '80s, when there was a Savings and Loan crisis (classic banking sector failure), the government stepped in and rescued all the S&Ls…oops, no it didn’t, it let most of them fail or merge (and sell off the bad assets). And, yes, that was painful, but it worked. It cleared out the bad ones - the pain was deep but short-lived - as the economy powered forward with less dead wood - without being zombified.

It’s good to go back and read the classics - Hayek, Schumpeter, Smith, etc. - as it helps you cut through all of today’s “sophistication” so that you see things like this: creative-destruction is the heart and soul of actual capitalism. All of this CB manna and Wall Street prestidigitation (securitization, balance sheet “management,” etc.) has stomped on that heart. We don’t let things fail - so no destruction - and many of our companies don’t invest in real new things - so no creation (obviously, I’m exaggerating, but you get the point).

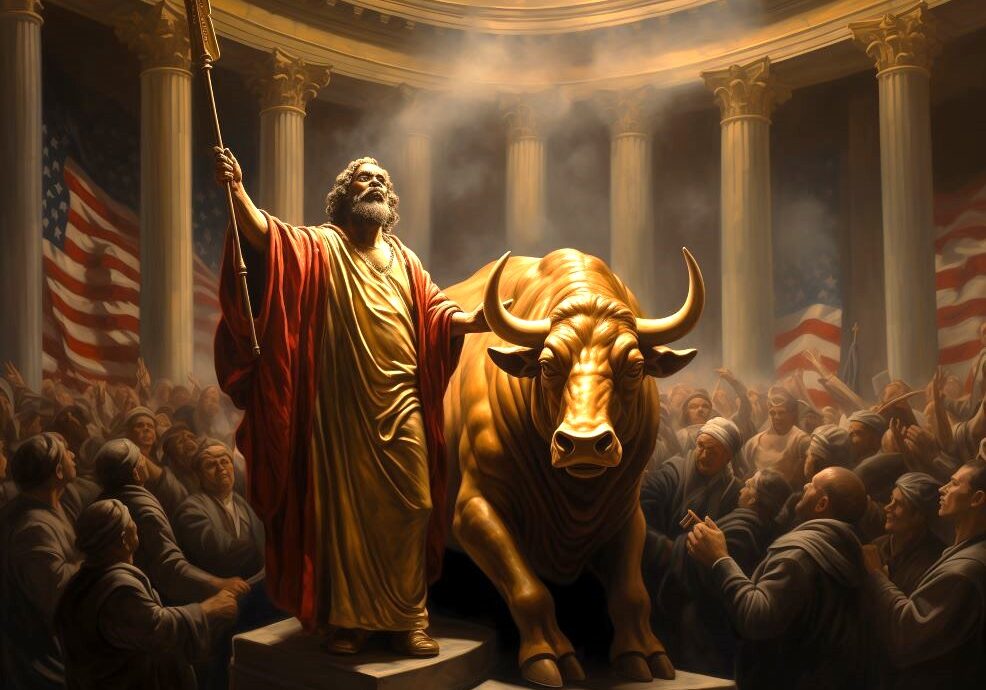

Ben’s right - we don’t have capitalism anymore. And this is the really, really, really bad part - the enemies of capitalism claim anything that isn’t the government is capitalism. So all this CB liquidity, QE, balance-sheet machinations, crony capitalism (where the government is as crooked as the businesses it “regulates”), securitization (squared), and on and on, is cited by the advocates of government “solutions” as evidence of capitalism’s failure.

Hence, privatization, deregulation, markets, business, money - all of it - is lumped in with the mischief of crony capitalism and CB manipulation as proof positive that socialism is the future and that capitalism has failed. Maybe I’m wrong, but I’d add that to Ben’s list of zeitgeist changes and, IMHO, that is the one that, if successful, destroys it all for a generation or more.

Good question, but it’s the other way around, I think, as Labor is calculated on national incomes and this is corporate data. In other words, I think that the declining share of household income for Labor is an effect of financialization, not a cause. If squeezing Labor was a cause of profit margin growth, you would (by definition) see increases in labor productivity. In fact, that’s why productivity numbers always spike when a recession hits … people get fired.