Recently I was asked to give a talk at a conference focused on connecting female fund managers to institutional allocators, and I uncomfortably agreed. Uncomfortably because women need another 59-yo finance guy “giving them a talk” like a fish needs a bicycle, and agreed because a) I want so badly to help, and b) I think I can provide a useful perspective on the Narrative-world dynamics of women on Wall Street that is largely separate from my age and y-chromosome.

So when I say “women on Wall Street”, I’m focusing on ‘risk-takers’, which is a term that has a specific meaning in finance. It’s someone who is taking risk or recommending risk in the technical sense of the word, meaning a discretionary allocation of capital to a non-risk-free security. It doesn’t mean risk-taking in the sense of running a red light or putting it all on black at the roulette table. On Wall Street, risk doesn’t mean high risk, it just means that the money is at risk. The typical examples of risk-takers in this context are portfolio managers and discretionary/prop traders (not to be confused with execution-only traders, who are just following orders), but for our purposes today I’m also going to include risk-taker adjacent positions like allocators, analysts, and investment bankers. Finance jobs that are not risk-takers include anything in compliance, anything in sales, anything in investor relations. If you’re a lawyer, you’re not a risk-taker. If you’re a psychiatrist/performance coach at Ax Capital in Billions, you’re not a risk-taker. All interesting jobs and all part of Wall Street, but not my focus here.

And when I say “narrative-world dynamics”, I mean the changing structures and archetypes of the stories we tell each other and ourselves, stories that are both created and reflected by popular media like movies and television. I’ve spent my professional career studying these story arcs and narrative archetypes, especially those we tell ourselves in the investing world. Plus, I … ummm … watch a lot of movies and television. So I’ve spent the past few days tracing the narrative archetypes around female risk-takers in movies and television shows about the banking or investment industries, and here’s what I found:

Prior to 2016, dramatic portrayals of female risk-takers (in the Wall Street sense) do not exist!

There’s not one female portfolio manager or trader or allocator or analyst or investment banker – someone whose job is to put other people’s money at risk – in any dramatic movie or television series prior to 2016 of which I am aware. Wall Street (1987), The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990), Boiler Room (2000), Money Never Sleeps (2010), Margin Call (2011), The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), The Big Short (2015) … forget risk-takers, there are hardly any women in these movies at all who aren’t wives or girlfriends or hookers or assistants. It’s really crazy! The one significant professional female role in any of these movies is Demi Moore as the Chief Risk Management Officer (the opposite of a risk-taking job!) in Margin Call, where – as all risk management and compliance folks suspect will eventually happen to them – she becomes the scapegoat for all the bad things that happen. Margin Call is, by the way, the best movie ever made about Wall Street by a mile.

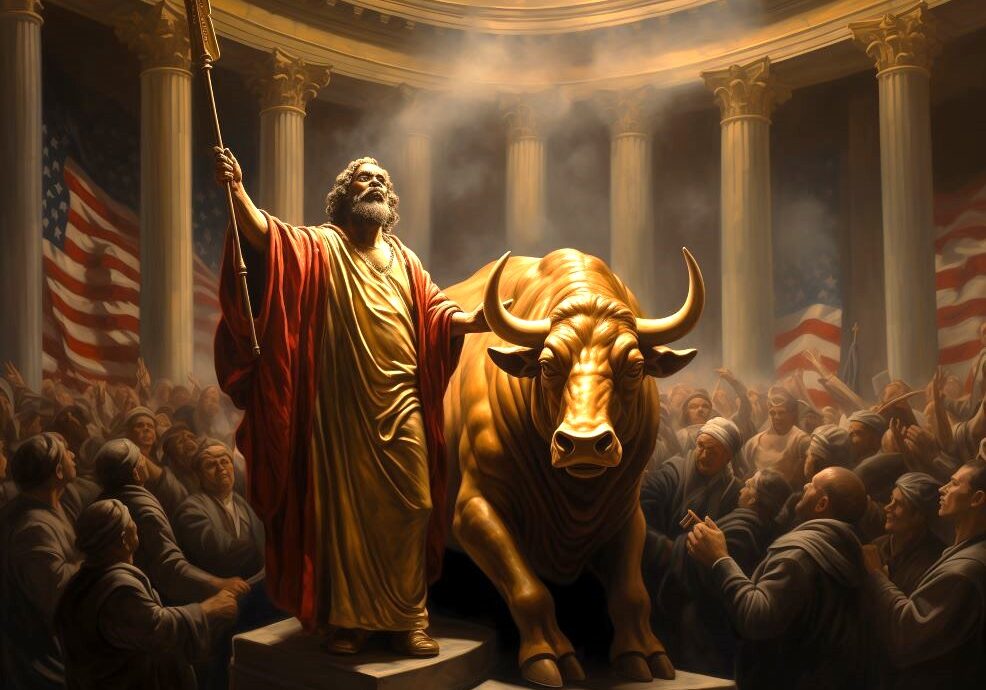

All of these movies embody a specific portrayal of women that I’ll call the Rounders narrative, after Ed Norton’s famous line in that film: women are the rake. Rounders (1998) isn’t about Wall Street, but the next best thing in popular mythology – gambling. Like movies about Wall Street, the notable thing about women in movies about gambling is that they don’t exist as risk-takers, as professional equals to men. And to the extent they exist at all in these movies – as wives, girlfriends or hookers – they are a distraction to the hero’s journey. They may be beautiful and loving (I mean, Gretchen Mol, Margot Robbie, Melanie Griffiths, etc. etc.), but ultimately they are a drag and a burden to the focused risk-taking that professional investing or professional gambling requires. As for whether women themselves are capable of that focused risk-taking that professional investing or professional gambling requires … haha! don’t make me laugh.

What is it about our society that all of these stories are written to make us

wantneed a character to eventually eschew the life of risk-taking and money making and instead settle down and go do literally anything else? When did we all become so divorced from reality that we cannot imagine a person—man or woman—who genuinely and truly wants to work a high pressure, high reward job and doesn’t need to quit in dramatic fashion and go start an emu farm with her best friend from grade school or whatever other fakakta ending they come up with?The Devil Wears Prada is the perfect ending for a writer to convey that they have contempt for their audience. It’s as if they knew we couldn’t have accepted a story arc that didn’t include the protagonist ultimately reverting to her mean rather than finding a way to make her new life more compatible with her old one. It’s the ultimate anti-feminism message that no girls, you cannot in fact have it all, you have to choose and we all know you’ll choose the handsome asshole boyfriend over the glamorous career. Maybe it’s more realistic—after all it was based on a true story—but as a work of aspirational fiction it’s utterly banal. Despite this it’s still a wonderfully entertaining movie, which is probably why nobody wants to dig up its bones and examine them for evidence of narrative homicide.

Fun fact: Both Simon Baker and Stanley Tucci appear together in two of the movies you mentioned, the aforementioned The Devil Wears Prada and Margin Call.

I hated Devil Wears Prada for the very reasons you’re stating. Streep was magnificent, of course, but the idea that the main character should feel guilty about being better at her job than the Blunt character was insane. Also, she—someone who wanted to be in publishing—had to leave New York because her chef boyfriend couldn’t find the right job there? What? No. She’s in publishing. She needs to be in NYC. You, boyfriend, CAN find a job in a restaurant in NYC and if you can’t, you should focus on your partner’s career because that’s going to be the highest use of your energy.

Nate is such a villain!

It’s so good until the third act! All the iconic moments come from the first two acts. We want to see Andy learn and grow and become the kick ass woman she always was inside. We don’t want to see her feel bad for being good at it.

“Oh no I’m good at my job in a way I never thought I would be and my boss thinks I’ve got incredible potential. Guess it’s time to quit!”

And great point about the publishing vs cooking! Nate’s just upset that his girlfriend is doing better than him!

I’m so glad you wrote about this, Ben! I’ve been investing in the stock market since my teens, and 20+ years later there are still no women financial risk takers I can read about/watch movies of. I have teen daughters that I’ve taught investing to, and I’m on a mission to teach more women stock market investing - it’s the only place where regular people with regular incomes can make a significant impact in their financial lives.

Excellent article, Ben! I have read this article a week back and keep on thinking why is Hollywood coming up with the idea of biasing woman against risk taking career, which is a common outcome whenever I read your articles.

I came up with a thought that Hollywood writers have an objective function for the central theme of a story that tries to maximize the likability in the society. The women in the risk taking career such as Wall Street are usually better paid and work for more hours than in an average job. Hence, there might be some envy tied to people who are not in that position. Also, the people who are in that positions believe that they are exceptional and not everyone will be able to do what they are doing. Moreover, the insecurity of not giving enough time to the family, which most of us do, like the idea of ‘you can but you shouldn’t’ type of mentality.

Hollywood writers hit envy, pride, and insecurity in the society with one theme and can feel happy about it. What they forget is that they are biasing young smart girls against a lucrative, intellectually stimulating, and fulfilling profession.

Since Hollywood is part of the theme here I would be remiss in not bringing this up.

The movie “Barbie”, where women fill every single position in society and men are all clueless bungling vanity projects. Every one of them except for the homely black-sheep “Allen”.

Some of my wife’s friends, even those with advanced clinical degrees liked the movie a lot, so they recommended it to her and I went along for the ride (HBO Max I think) at home.

Both of us hated it equally, perhaps in part because we raised two well adjusted boys into successful independent young men. “Barbie” is divisive and perpetuates the widening-gyre even more throughly along the gender lines.

I worked as an RN in a teaching hospital in the 90’s for 4 years, and considered myself a bit of a Feminist then. Got along great with everybody at work, a good dynamic. Always a big equal opportunist, my support of “feminism” or Feminism TM has waned over the past decade, and now it’s over.

Done.

Would appreciate your take on this @harperhunt