PDF Download (Paid Subscription Required): By Our Own Petard

For ’tis the sport to have the enginer

Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 4, by William Shakespeare

Hoist with his own petard; and ’t shall go hard

But I will delve one yard below their mines

And blow them at the moon. O, ’tis most sweet

When in one line two crafts directly meet.

Peter Gibbons: It’s a problem of motivation, all right? Now, if I work my ass off and Initech ships a few extra units, I don’t see another dime. So where’s the motivation? And here’s another thing, Bob. I have eight different bosses right now!

Bob Slydell: I beg your pardon?

Peter: Eight bosses.

Bob: Eight?

Peter: Eight, Bob. So that means when I make a mistake, I have eight different people coming by to tell me about it. That’s my real motivation – is not to be hassled. That and the fear of losing my job, but y’know, Bob, it will only make someone work hard enough not to get fired.

Office Space (1999)

I would like to start, as every good essay ought to do, by offering you a heuristic I have pulled completely out of my ass. Or out of a career dedicated to understanding the behaviors of the people who allocate to investment managers, which basically amounts to the same thing:

Ask the novice adviser or allocator what matters most, and their answer can usually be reduced to historical performance.

Ask the journeyman, and the answer you receive will be reducible to the identification of #edge.

Ask the master, and they will tell you about alignment.

I don’t mean this to be condescending. Truly, I don’t. I also don’t mean it to be dismissive of any methodology or philosophy for the selection of professional investment advisers and managers. But the incredible degree of difficulty (read: mathematical impossibility) of achieving results consistently worth the fees paid to external advisers, coupled with the tendency of the math to bang that reality into our heads over the course of a career, is almost tautologically geared to this intellectual progression in the evaluation of investment strategies:

Induction -> Deduction -> Deconstruction

Scientism -> Kinda-Sorta Empiricism -> Evo Psych

Historical Performance -> Analysis of Edge -> Alignment

The inevitable final form of the professional allocator or adviser is not so much the nihilist as the practitioner of serendipity. They recognize that randomness reigns and control what they can control. In a perfect world, they control what they can control by leaning on lasting, demonstrable, biologically determined human behavioral traits to try to guide someone they think is talented and process-oriented to results that will benefit both principal and agent alike. It is a stoic, right-sounding, eminently reasonable, perfectly justifiable framework. There’s just one problem. A tiny, insignificant problem that I almost hesitate to mention:

We will never – can never – be aligned with our agents.

As citizens, shareholders and investors, we worry with good reason that the agents working on our behalf – our political representatives, corporate management teams and the investment consultants, advisers and managers we rely on, respectively – actually will work on our behalf. Preferably for a reason that goes somewhat beyond ‘not going to jail’ or ‘because they seem like someone you could have a beer with.’ We want them to feel like they have skin in the game. Like we both win if either of us wins.

When we, as a principal, select an agent, we have every reason to shout “Yay, alignment!” from the rafters.

And because we have every reason to shout “Yay, alignment!”, our agents have every reason to sell us compensation structures which permit them to extract undeserved economic rents by demonstrating the superficial trappings of alignment. This job is made a hell of a lot easier by the fact that we investment professionals – nominally principals in the relationship – are often ourselves agents of some other party. We are using delegated authority to act on behalf of a client, a family, an institution, a board. People to whom we need to demonstrate alignment.

Necessity being the mother of invention and all, our need for a story that will make us or our own charges shout “Yay, alignment!” makes us vulnerable to structures and features from our agents which don’t deliver anything of the sort – but seem to.

Hoisted by our own petard, as it were.

And here’s how it happens.

Let’s start with what has long been Common Knowledge – what everyone knows everyone knows – about alignment in our little corner of the world:

Commission-based models are bad.

What we all know that we all know is that fixed commission-based compensation models represent poor alignment of incentives because the adviser who is paid on commissions has an incentive to generate commissions by executing trades. Even Chuck here, who is nearly a deca-billionaire because of the decades he charged clients commissions, knows that the tide is going out on him. He wants to re-cast himself on the right side of history.

Just so we are 100% clear about this, the single human being who may have built the greatest personal wealth by charging clients commissions is now shaking his finger at us to tell us how much he hates them, and how we ought to think about them. Just marvelous.

Whether Chuck’s come-to-Jesus is authentic or not, we are now all in on the joke. The natural incentive implied by commission-based compensation is to take actions which would harm the client. Simple enough. Fair. Some will make the ‘Yes, but if I don’t make good trades I’ll lose the client and I don’t want to do that, etc.’ argument, but I feel confident that even those folks get the basic criticism. Full-hearted FAs can absolutely deliver good client outcomes under a commission structure. But their incentive is not to do that. It isn’t complicated.

I also think most people understand intuitively the disconnect between paying a transactional fee for something and expecting that person to want to do a better job on that thing. We structure many of our commercial relationships around the introduction of performance-based variability. In America, anyway, we pay restaurant and bar service professionals primarily through variable compensation: tips. We structure our companies’ compensation around bonuses (which, truth be told, almost universally tend to vary around corporate results far more than personal performance). In significant swaths of the legal profession (excluding corporate law, where the goal is to find lawyers we can pay enough to offload the career risk of a botched deal structure), we pay on contingency.

If an agent’s primary incentive is to get you to do a specific deal – and that is very frequently the case with those paid on functionally fixed commission – it’s easy to see how that doesn’t satisfy our desire for alignment. The cases where high, fixed, transactional fees for one-off services are still the norm are accordingly almost always industries protected by forms of occupational licensing. In some cases, like, say, medicine, those licenses and the fixed compensation models they contemplate seem legitimate. To me anyway. Feels a bit unseemly to pay someone a bonus for doing an especially good job removing a cancerous mass. In other cases the fees are simply the result of lobby-protected oligopolistic behavior. Classic rent-seeking. Real estate agents, we are all looking square at you and your patently absurd 6%.

(And yes, if you send me a bulleted explanation of why that 6% is justified, straight out of some brochure given to new agents by the National Association of Realtors, there is a 100% chance it will be reprinted on these pages with all sorts of friendly annotations from yours truly.)

In almost all of those cases, and certainly in the investment industry, the next step in our evolution toward Yay, alignment! was to move to a relationship-driven, asset-based fee or fee-for-service model. This form of better alignment is the rallying cry of the independent registered investment adviser and investment adviser representatives against their brethren at banks, wirehouses and independent brokerages.

So is this industry-wide move from commission-based to fee-based advisers good? Did it actually move us in the direction of better alignment?

Of course it did.

But not nearly as far as we all want to pretend.

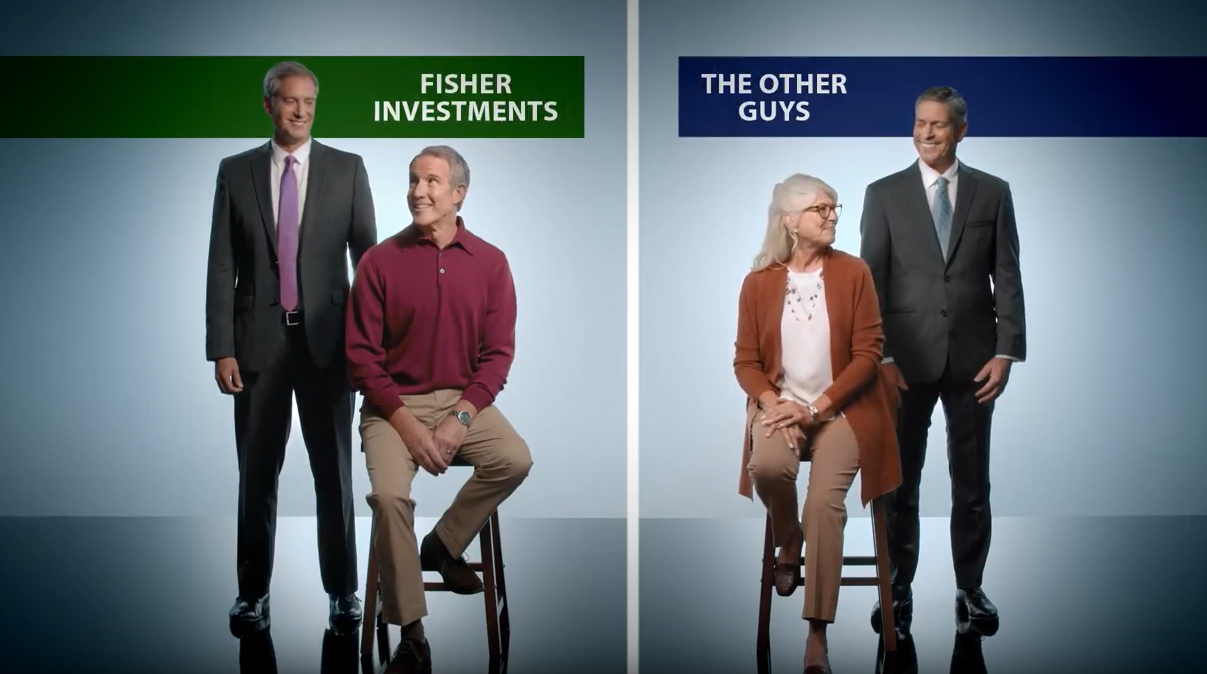

Asset-based fees, management fees, advisory fees – whatever term of art your corner of the industry wants to use – eliminate the incentive to churn, but aligned? Come on. And in case you were wondering, this is absolutely a trope that is marketed to you to exploit the Yay, alignment! Meme. For example, before Fisher Investments professionals were festively describing to conference-goers how selling to individual investors was like ‘getting into a girl’s pants’ (no, really, this is an actual thing that happened), they were spooning out hot garbage like this advertisement below.

Remember this?

The name of the ad spot is, “We do better when you do better.” This is the Yay, alignment! hook as she appears in the wild. I guarantee you the script to this thing recommended casting a substantially taller guy with an unbuttoned suit as the Fisher guy. In practice, some 90% of the amount of any asset-based fee without a fulcrum structure in a given year is going to be driven by whatever capital you gave the adviser to manage to start the year, and the lion’s share of the remaining difference will be driven by market returns outside of the adviser’s control. For an average balanced portfolio, the amount of the asset-based fee that reflects the job that was done? Maybe 2%, if you’ve got someone generating some tracking error by overweighting value indexes and emerging market stocks a little bit.

So, yes, the Fisher ad is bad and they should feel bad. Still, even if advisers don’t really do better when you do better in any real way that measures up to the meme, surely whatever incentive replaced the incentive to sell whatever you could sell is better.

What, then, IS the incentive for the fund manager, adviser or consultant in an asset-based fee framework?

To keep clipping coupons on your account.

In our heart of hearts – that is, when we aren’t justifying to someone else why people in our industry should be paid what we all get paid – we know that working hard enough to not get fired isn’t alignment, Bob. Not even close. But we’ve all perfected the tortured way in which we pretend that it is. The best part is that we get to summon the Yay, alignment! meme in a particularly special way while we do it. And what an empowering message it is: ‘If the client isn’t happy with the results, we don’t get paid. What could be more aligned than putting all the power in the hands of the client?’

See how easily bullshit rolls off the tongue when it’s wrapped in these seductive memes?

Don’t get me wrong. We can wish that paying people in this industry weren’t so expensive, or that accessing the circa-1987 technology in a Bloomberg terminal didn’t hit our P&Ls to the tune of a new Camry every year, but wishing won’t make it so. You’ve got to charge management fees. We do too. And doing so is usually going to put us in better alignment than commission-based compensation. But let’s drop the theatrics, people.

Paying asset-based fees won’t align you with your agents.

Except most of us rather like the theatrics.

So instead of dropping them, we double down. No, that’s not right. We lever it up ten times and call it super-aligned. How? By looking for and preferring equity ownership on the part of fund managers and financial advisers.

And look, I get why this is such a good-sounding thing. There is such a native appeal to the Narrative of the guy-with-his-name-on-the-door who has real skin in the game, who would never let any of his clients be mistreated, lest his good name be besmirched. I get it. But the idea that this is the primary incentive created by equity ownership strains credulity. Take an honest look at what’s happening in the RIA space. Record number of M&A deals in 2016. We broke that record in 2017. Then we broke that record again in 2018. Similar consolidation cycles in many segments of the asset management space, too.

Folks, if you do business with an investment company that charges you an asset-based fee, there is a spreadsheet somewhere on their network drive with your name in Column A, your most recent AUM in Column B, your effective annual fee rate in Column C, and the number 10 (12 for people who hire aggressive bankers with shady comps) in Column D. In Column E is the amount of money they take off the table by selling your account to somebody. Buyers don’t pay very much for performance fees, and they aren’t crazy about things they perceive as being one-time in nature, like financial planning fees or estate planning fees. But recurring asset-based fees? Money in the bank.

Incentives don’t follow a direct path to behavior, of course. They pass through all sorts of work ethic, moral and process layers on their way, and so a decent human being with bad incentives may end up producing better results than a real jerk who ought to know where his bread is buttered. But find me an RIA principal thinking about selling his firm in the next 18-24 months, and I’ll find you a guy who doesn’t say no as often as he should to his clients’ insane IPO requests, who hews to US stocks and vanilla high-grade laddered munis, who wouldn’t give a thought to working to identify that higher volatility source of diversification for you. There are few incentives which I have observed having as direct an influence on realized behavior as an interest in the capitalized value of a management fee stream.

Now again, the point here isn’t to say that these aren’t things you should accept, or that they are Very, Very Bad. They aren’t. For better or worse, this is how our industry works right now. But if your diligence guidelines describe how you think equity ownership aligns an investment professional with long-term financial prudence and fiduciary principles and blah blah blah, you are deluding yourself. Sorry. I should know. I deluded myself on this point for a very long time. It aligns them with not pissing you off until they can get someone to pay them 10x against the run-rate revenue on your account.

This incentive not to piss you off doesn’t make them evil. It doesn’t make it worse than other bad forms of alignment.

But it also doesn’t make them aligned with you.

Most of us get this. Grudgingly, perhaps, but as long as someone isn’t trying to get us to agree to this in context of an argument about the level of compensation in the investment industry, we will usually go along with it. And if the SEC didn’t make it nearly impossible to charge performance or pseudo-performance fee structures (e.g. fulcrum fees, etc.) for retail investors or in the most common retail vehicles, I think many of us would do more than go along with it. We’d put our money where our mouth was and slap performance-based fees on everything.

Except, well, it’s probably performance fees that sing the most seductive Yay, alignment! song.

On the surface, it is hard to imagine anything more aligned than performance-based fees. You pay when you get performance. You don’t pay when you don’t.

Except that, like, you do.

There are two reasons why this is true. The first is well-trod, and so I won’t dwell on it too much. I will, however, say this: anyone who is paying performance-based fees for beta in 2019 is a sucker, and anyone who is charging performance-based fees for beta in 2019 is a Raccoon. While there are blessedly fewer than there were a decade ago, there are still long/short equity and credit managers with persistent net exposures of 40-60% who argue that their net is not really beta but the outcome of an alpha process. It’s a garbage argument. They know it. You know it. And no matter how confident we might be in their edge or alpha generation potential, the odds against that ever realistically measuring up to 15-20% of that 40-60% beta exposure are astronomical. A performance-based fee on functionally static beta is a management fee. Again, this wouldn’t have been a novel observation even 10 years ago, but in the interest of completeness, a client paying performance-based fees on beta is in no way aligned with their manager.

There is a second issue, however, which consistently and structurally favors the chargers of performance-based fees against the payer: we systematically understate the experienced asymmetry of realized performance fees as a percentage of gross portfolio returns.

Here’s what I mean.

Let us say that you are an asset allocator with the opportunity to invest with a hedge fund charging a 20% performance fee. Let us be generous and presume that you would be likely to terminate this manager only if they (1) lost more than 10% in absolute terms since inception or (2) experienced a drawdown of more than 20%. Now let us assume that this manager has absolutely zero skill. A real Greenwich special.

Over a five year period, how much do you think you would pay in performance fees? Our analysis is too path-dependent for a closed-form solution, so let’s play it out 100,000 times for various levels of portfolio volatility. We are examining the realized fees that would be paid annually as a percentage of assets, making certain (pretty realistic) assumptions about when we would probably fire the manager. Each point on the below chart is the average from those 100,000 simulations for each level of volatility.

The gray line shows across each of those simulations how much, on average, you should expect to pay in performance fees per annum during years in which you are invested. Remember, this manager has zero skill. You have no expectation of long-term alpha.

In other words, for any realistic expectation of the life-cycle of an invested relationship with a manager that charges performance-based fees, you might expect to pay roughly 80% of the manager’s annualized volatility (multiplied by whatever the performance fee rate is) in performance-based fees every year FROM SHEER RANDOMNESS WITH ZERO EXPECTATION OF REAL ALPHA.

That is the power of the asymmetry of paying performance-based fees when they are earned, but almost never recouping them when that performance is lost. Now, it may be hard to visualize some of the most egregious scenarios that roll up into these aggregates, so let us now take a look at the distribution of fees paid against gross returns generated at a particular volatility level. Let us consider a hypothetical skill-less manager with 8% volatility.

Again, what we’re doing here is randomly generating returns for an 8% volatility manager for each of 5 years. We pay fees at 20% of alpha at the end of each year above the high-water mark, and we terminate the manager if they have lost more than 10% absolute since inception or if they have experienced a drawdown of 20% from their high-water mark. Each dot below shows one of the simulation outcomes over that five year period, where the X-Axis represents the cumulative (non-annualized) gross return and the Y-Axis represents the percentage of assets that have been paid in fees over the corresponding period.

It should be intuitive that the slope of the diagonal line reaching upward to the right at the edge of the dots is 0.2, or 20%, the performance fee rate. Perhaps less intuitive for those of us who haven’t accustomed ourselves to thinking about performance-based fees in a path-dependent way is that a huge share of the outcomes end up with us paying way, way more than 20%, at times with seemingly no real relationship to the amount of value added. Remember, these are simulations of the outcomes for a pretty normal investment manager with ZERO SKILL.

See everything to the left of the blue edge sloping at 0.2x, or the 20% performance fee rate you sold to your board? Those are cases where you paid more than 20% in the aggregate over a five-year period. See everything to the left of the sloped black line? Those are cases where you paid this no-talent clown more in performance fees than the total gross performance they generated. In around 57-58% of these cases, your manager produced negative cumulative returns by the time you canned them. In about 47% of those cases, you still paid them a performance fee. In about 60% of those cases, that fee was more than 1%.

Friends, this is the water in which your incentive alignment structure swims. This is the bogey, the noise against whatever signal exists in your manager’s alpha/performance fee relationship must compete for us to consider it true alignment.

In any realistic path-dependent analysis, performance-based fees are far too noisy to align you with your managers.

So why do these fees exist?

Maybe because they can occasionally be structured to truly reflect a shared set of interests. Truly. It does happen.

Maybe because for some rare sources of alpha, even the likely elevated realized performance fee experience will be worth it.

But really? They exist because people who can charge these fees know that asset owners have boards that feel better and are less concerned about paying fees in particular periods where the returns are very good. They know that when we present funds for approval, we all show the linear scenarios of fees paid in different return scenarios, and that we heavily sell the downside scenarios where we don’t pay as much as we would under a management fee heavy structure. They know that we never, ever show the path dependent scenarios in which we pay fees early, hit a drawdown and terminate, and they know that no one ever, ever asks to see that illustration – even though it may be among the most inevitable outcomes in all of finance.

There is bigger game afoot here, too. In a very real way, by embracing the Yay, alignment! meme so wholeheartedly, we have institutionalized the ability of a class of individuals to extract mathematically inevitable rents from the act of doing nothing other than taking risk with our money and the money of our fiduciary charges.

So what do we do? If most of what we call alignment are right-sounding cartoons which enable massive compensation schemes, how do we achieve real alignment with our financial advisers, fund managers and consultants?

Simple. We don’t.

Sorry, were you expecting a panacea? There isn’t one. You cannot structure away principal-agent problems. And that’s the point. The manipulation of the meme of Yay, alignment! is designed to make you believe that it is possible to do so in order to agree to compensation schemes and arguments for ‘alignment’ of incentives which do absolutely nothing of the sort.

But here’s what we can do:

- We can demand beta hurdles: Guys. It’s 2019. Friends don’t let friends pay fees for beta. Stop doing it and stop explaining it away. When they tell you their consistent 40-60% net long exposure is an outcome of their alpha process and not really a beta, tell them they are full of it, and move on if you can’t move them off it. Seriously. You should already be skeptical about alpha. If you are paying 15-20% on a static 0.4-0.6 beta AND paying the volatility tax, the hurdle on your alpha expectations will be insurmountably high for just about any fund manager in the world.

- We can look more favorably on multi-year crystallization fee structures: These were all the rage a few years back, especially among more long-biased equity funds. Still, some liquid markets managers have and continue to offer multi-year crystallization on incentive fees in exchange for lockups on capital. My view is that the price you should demand for illiquidity is nearly always dwarfed by the benefit you gain from functional clawbacks on performance fees that would have been moot with shorter horizon fee crystallization.

- We can more eagerly pursue cross-fund netting: As allocators, we feel inclined to spread capital around to specialists. It feels right. It feels sophisticated. It feels like we’re doing the work we are paid to do. But the path-dependent power of getting to net the performance-based fees of multiple funds from a single investment partner with multiple investment capabilities often exceeds whatever “uniqueness” benefit we typically get from spreading assets around to smaller, less capacity-constrained, more ‘hungry’ boutiques. Sorry. I know that’s going to be an unpopular view. But asymmetry is a curse. Not nearly enough large, influential allocators take advantage of this.

- We can start paying more attention to our advisers/managers’ incentives to sell their firms: There is little more destabilizing to our simple point-in-time estimates of incentive alignment than the hidden calculus of how much an investment firm is worth. We can spend less time thinking about how much someone’s name on the door will make them act honorably, and more time thinking about how much a 10x multiple slapped on our account will make them act irresponsibly with our money.

- We can be very careful about the volatility tax we pay on our own behavior when hiring higher volatility managers with incentive fees: As we start to become more selective in our use of alternatives, we will often – appropriately – drift toward higher volatility, higher leverage or higher tracking error strategies to make better use of our various budgets. But take care: the bogey that we are charged in practice on the asymmetry of performance-based fees becomes particularly egregious on higher volatility strategies. If we must go this direction, relying more heavily on systematic managers who more explicitly track, target and limit risk seems prudent.

But most importantly, we can stop thinking that we can and will ever be aligned with our agents. We can’t. We won’t. And the sooner we realize that, the sooner we will also realize that anything being sold to us under the meme of Yay, alignment! ought to be seen with Clear Eyes. Not dismissed. Not rejected. But understood for what it is, lest those we hire to represent our interests hoist us by our own petard of ‘alignment.’

PDF Download (Paid Subscription Required): By Our Own Petard

Complex systems. Simple rules. What if technology strips away everything in the current financial advisors tool kit? Ben’s “three-body problem” obliterates the pretense of “active” investment management, Joe Duran’s assertion at WealthStack that financial planning will ultimately be fully automated, etc. What if everything is replaced by automated systems with the next leg up in computing power? Rather than discarding the advisor completely, what if it creates a need for an entirely new and different kind of advisor? One whose only function is to share their “human” life experience as the foundation for their ability to offer advice in the first place. An Advisor who makes sense of all the data by leveraging their “soft skills” rather than falsely trying to predict the future. What if all this discussion around fees and commissions and AUM and RIA spreadsheets is really just noise? Of course it’s all bullshit and backwards and wrong. Information asymmetry made it that way and the thundering herd kept it that way. But technology is forcing its hand in a way very similar to the Industrial Revolution and the emergence of Artificial Intelligence and higher order computing power will take all this bullshit away. You say “alignment” is impossible. I think its the only way an advisor can survive going forward. The value add for an advisor will be precisely that which aligns them to their ideal client. If their life history and ability to navigate through the pitfalls and hardships of life resonates with the end client, then they will inherently share aligned interests. It will not matter what firm they work for or how much AUM they have or how much they charge in commissions or how many credentials they have on their non-existent mahogany walled office. The only thing that will matter will be that there is this advisor who has been through some really difficult experiences in life and managed to get to the other side. You know what, that’s really similar to what I am going through. Maybe I should reach out and see if we can work together. Might save me a lot of money and pain. How will I find that advisor? Simple. They are everywhere and being vetted all the time on social media. Their calling card is their story, that’s it. Go find the one who’s story resonates with you because your gonna need someone in your corner to defend you against the giant tech companies who have already stolen all your data and are using it against you.

So, in a way “Yay, alignment!”. Maybe I’m wrong, but I hope not.

It took me a while to absorb the message in the chart that drilled in on the distribution of outcomes at 8% volatility. Once I understood it, my entire view on performance fees changed. That is some powerful stuff Rusty. Well done.

I think you and I probably agree, Thomas.

I personally do NOT believe that advice will be arbitraged away by technology. I believe that the single most powerful form of alignment comes when we recognize that the “technical” forms of alignment we try to engineer through fees and diligence checklists are anything but. That form of alignment is a human relationship with someone that has made themselves vulnerable to us and us to them.

I think an adviser who can deliver that to a client, and a client who can absorb that into their decision-making framework, will be more aligned than anyone who doesn’t, regardless of the incentives of their fee structure. It’s a touchy-feely sort of thing to say, but I absolutely believe it, and it’s why I still believe in advice.

Thank you for the reply and for all your work. I cannot begin to quantify how much your writings have meant to me. Very much appreciated.

Thank you! This is one of the things that I have been trying to explain to clients and regulators ever since the Department of Labor released its Fiduciary Standard. There is no such thing as conflict free humans. There is no ideal compensation method. Every one of them has a conflict. Commissions are evil? Taken to excess, sure, but if you are a buy and hold investor it can be the cheapest way to pay for occasional advice. Advisory fees are perfect? Why does the SEC have a bulletin on reverse churning? (Charging Advisory fees, but not trading frequently enough to make the advisory fee cheaper than a commission model.) Advice only model? Who will help me execute the advice? I get a blueprint, but how do I pick a contractor to make it real?

Don’t even get me started on updating the regulations. Bernie Madoff, Ken Lay, and numerous others were fiduciaries for their investors. It did nothing to protect the investors. Governmental regulations are like a warranty. A warranty may force the manufacturer to repair their product, but it won’t prevent the hassle and other costs associated with a failure in the product. A strong warranty does not make up for a poor quality product. I would rather have a high quality product with no warranty. (Also, any car dealer will tell you that warranty repairs are the ultimate in misaligned incentives.) Technology will take an extremely long time to replace human interaction. (if it ever does.) No one cares about hurting a computer or robot’s “feelings.” We feel beholden to other people. How do I know? Look at physical fitness. How many people have lost weight, improved their diet and turned their life around because they bought a Fitbit or Apple Watch? How many have done it with a personal trainer and/or nutritionist? Investment analysis, portfolio design, portfolio management, financial planning, tax analysis, budgeting, really all of the math components of financial success will be automated. I’m sure there will be several different competing tools. None of them will take the place of a caring human financial advisor that will encourage you to use the tools, understand the differences between them, and provide personalized interpretation (wisdom) on using them to maximum advantage. I don’t work with institutions, I work with people. People want a caring guide to show them the ropes, identify the traps, and generally help them do better than they could do on their own. My clients are part of my packs. I use this part of my pack to help me do a better job for that part.

Excellent long piece as always. Thomas, triple thumbs up.

Rusty-I’m reminded from a line in an Indiana Jones movie, “Son, we are pilgrims in an unholy land”. I’m a discretionary fee-only FA who runs what in effect is a hedge fund for widows and orphans (no 2/20’s or performance fees). I’m getting killed by fee compression. It doesn’t matter that my PERSONAL investable money is right along side my clients’ in the same portfolios, and I pay the same or HIGHER fee than they pay. I can’t possibly be more “aligned” as I suffer or prosper right along side them in both income and wealth. However, such a message/meme never resonates in a market environment that can only be described as the never-ending money chase orgy of free money. Thank you Fed. My approx. 80% of S&P capture with approx. half the risk for nearly 20 years does NOT resonate in the market place. I can only take solace from the notion that a replay of my lower risk 2008 “over” vs the S&P will happen again rewarding those who ignore the Siren’s song of no-risk, no-cost passive indexation and stayed with me.

I’m reminded of, “The problem with doing the right thing is that you often do it alone”. Damn, I feel lonely out here!

I couldn’t agree more on just about every count. Thanks for reading.

Yes, Peter, and it’s not just the free money out there. It’s the fact that people who are decidedly unaligned get to hang out their “yay, alignment” shingles and pretend that just going fee-only, or just talking up fiduciary language is doing the same that as what you have done.

One of the most pernicious powers of narrative is that it cheapens the real thing whenever it does come along.

The thing many fee-based clients don’t understand is this: they are subsidizing commission-based clients. My commission clients (usually older, buy-and-hold, low maintenance people) don’t do nearly enough trading to justify charging them a fee. But they still get phone calls, meetings, Christmas cards, and all the services they need. But maybe they make one or two trades a year. Without the fee-based people essentially paying the bills these commission clients would be passed off to someone else or sent online. And they don’t want that. A lot of them have been with my family for decades. We have relationships. So they get everything they need and it costs them very little. It’s a great deal for them.

P.S. With how rich Ken Fisher is you’d think he could afford a suit that fits him. The guy looks like he’s wearing his older brother’s suit that he bought for the Homecoming dance in 1987.

Hi Rusty. Re your recommendations, how do you suggest calculating the beta hurdle, adjusted for long/short exposures? Thx