George Soros has a great line that we've used a lot in Epsilon Theory notes. When he was asked how he could possibly have predicted what would happen when he famously "broke the Bank of England" in 1992, he replied in that growly Hungarian voice: I'm not predicting. I'm observing.

It's the perfect catchphrase for the modern, Narrative-savvy investor. It's the perfect catchphrase for the Three-Body Problem market, where there is no algorithm for predicting markets (no closed-form solution, in the lingo), but only tools for calculating markets. Where there is no Answer for successful investing. But there is a Process.

I'm not predicting. I'm observing.

The interesting piece here is that in March-May 2020, the case was made (rightly so) that wages bounced because a huge chunk of lower-paid workers got axed in retail, restaurants, travel, entertainment, and other services industries. Thus, the labor force in the spring of last year was left with a bunch of workers in higher-income positions, so the jump in wages that we saw at that point could be explained by showing 30M people out of work in low wage jobs, and so average wages slid up even though it wasn’t like everyone suddenly saw their incomes jump because of COVID. Not at least with how BLS calculates it for this report.

But if we’re looking at it now, the question for those businesses in those sectors that are trying to reopen and trying to rehire is that this was not a seasonal closing where you go back and find the workers from last year and bump them from $11 and hour to $11.25 an hour. This was the biggest one-year labor disruption in history. A ton of people moved. A ton of people retired. A ton of people changed industries because they saw friends getting paid more in other businesses. A ton of people are still dealing with kids remote learning with no childcare. Businesses aren’t simply hiring back the same employees at a slight raise now.

They have to compete with the higher wages that some of their workers have gone out and taken in the last year. They have to find new employees to replace the ones who moved. They have to pay enough for parents to be able to afford babysitters to watch their kids remote learning and make sure the house doesn’t blow up.

So while last spring’s jump in wages at the same time we saw tens of millions of people getting axed can be explained by the type of workers who were laid off en masse and their wages, the labor market has shifted because those workers weren’t simply stagnant waiting to return to the same job they had previously. Those industries are not competing within themselves for workers anymore. They’re competing with the higher wages and stability that exist in the industries that weren’t shuttered.

Ultimately, it’s a good thing for the American worker to be able to have a chance to see wage gains. I don’t bemoan it, and I think given the trends of the last 40 years, it would be tough to find fault with Americans who are finally seeing the tables turned and taking advantage of a labor market that is in their favor for the first time in a generation. But wage inflation is the sticky kind of inflation. If I cut down an oak tree, it doesn’t care how much its timber gets sold for. It has no pride in the price of its services. But if I pay Sally $15 an hour this year, she’s gonna lose her shit if I tell her to come back next summer at $13 an hour. So unlike the bumps we’re seeing in lumber prices, used car prices, and things without feelings, wage inflation is the piece that likely makes this inflation stick. And it makes it stick in the two of the three sectors that have been the dominant trend in employment growth in America over the past 50 years - restaurants and travel.

Prepare for takeoff.

I will echo a few of the points that @Canid brought up. Initially average wages went up solely because lower earning employees were laid off. Now with those employees being rehired, average wages should go down. I would have to take a look at the actual employment numbers and hours worked to see if you wage data has captured this properly. I am not disputing your narrative I just want to make certain that you have captured the above mentioned facts.

Now I will tie in John Hussman (mentioned in the ET Forum). One of Hussman’s favorite valuation measures which he uses to predict 12 year forward earnings in the stock market is what he calls MAPE (Margin Adjusted Price Earnings Ratio). He has long stated that businesses have record high margins partly due to low earnings by workers and that this would change and his MAPE calculations call for no or negative twelve year returns partly as a result of this. So obviously higher wages will result in lower earnings and potentially lower equity prices.

I am not looking forward to another bout of inflation. Dealing with inflation usually takes ones effort off of more productive endeavors.

All of which suggests a very nice level of heterogeneity may develop in stocks as companies with pricing power (the way we used to invest back in the inflation day) are treated differently over companies with no ability to move prices.

Risking some personal inflation, your observations are worth every

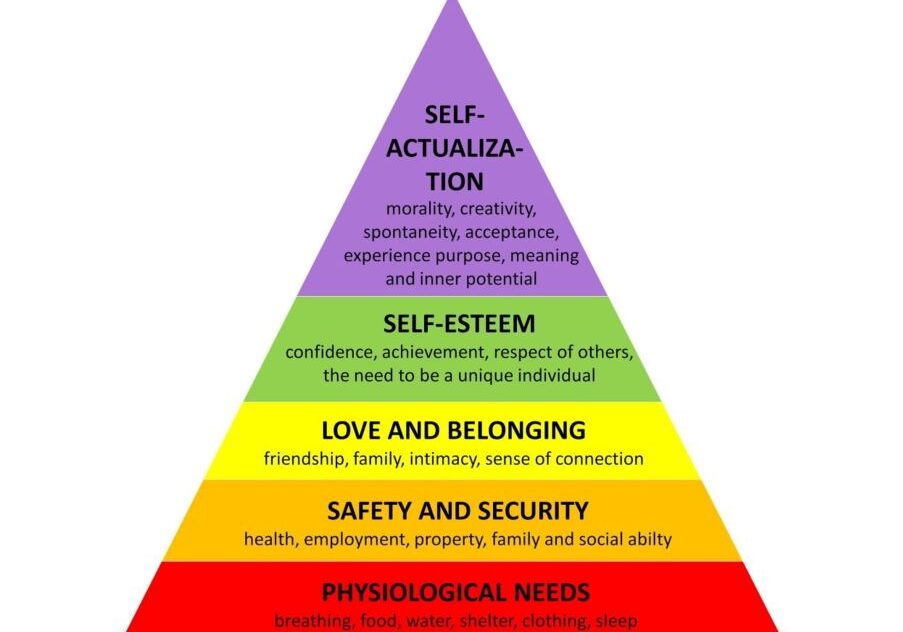

pennynickeldime of the subscription price. Not that it solves anything, I just wonder how many people spreading these narratives are complicit and how many are unknowing mouthpieces repeating the spin.So in terms of Rusty’s Things We Need to Be True, a change in Common Knowledge would take out at least his top3:

- By definition

- MCD and CMG can't prepare and serve food in local markets over Zoom from India.

- To Ben's point about the Fed being trapped in their own narrative, if they admit it's not transitory, they might have to do something about it.

Yikes.The Fed just reported that it’s balance sheet ballooned another $32 Billion last week. That’s a 23% annualized increase over 3 months and 89% growth rate from 1 year ago.

Insane rate of increases in an environment already of rising inflation .

How they can justify printing massive quantities of money is beyond me.

I am trying to better understand Ben’s points above. I get that hourly wage growth is being mathematically depressed by longer working hours. But I assume this is only for those that are actually employed?

Can we assume that there IS still slack in the US labour force that WILL come back once all the stimulus cheques and other programmes stop or shrink? Can I assume this is the case when I look at the underemployment rate (at 10.4%)?

I don’t know the answer to this but it’s important to understand this in the context of whether or not this is “transitory”.

The Fed and the government remind me of an alcoholic that is hitting bottom. The lies that they have used to build their house of cards is starting to get wobbly. They must know tell more ridiculous lies to cover for the lies previously told.

Now not know —we need an edit button.

button.

You should read https://mishtalk.com/economics/the-psychology-of-qe-is-far-more-important-than-the-amount-of-it including the John Hussman article linked inside. The John Hussman article is also linked in the ET Forum article “Hussman Letter”. The Fed balance sheet is not inflationary because the money goes nowhere but sits on the books in banks. It does have an effect on interest rates however. The “helicopter” money (deficit spending) is another matter especially if it doesn’t get paid back. That money goes into people’s pockets for them to spend.