The NFL Has a Gambling Problem

To learn more about Epsilon Theory and be notified when we release new content sign up here. You’ll receive an email every week and your information will never be shared with anyone else.

Continue the discussion at the Epsilon Theory Forum

25 more replies

The Latest From Epsilon Theory

This commentary is being provided to you as general information only and should not be taken as investment advice. The opinions expressed in these materials represent the personal views of the author(s). It is not investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. Any action that you take as a result of information contained in this document is ultimately your responsibility. Epsilon Theory will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information. Consult your investment advisor before making any investment decisions. It must be noted, that no one can accurately predict the future of the market with certainty or guarantee future investment performance. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

Statements in this communication are forward-looking statements. The forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date of this publication. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Epsilon Theory disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein. This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. This commentary has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. Epsilon Theory recommends that investors independently evaluate particular investments and strategies, and encourages investors to seek the advice of a financial advisor. The appropriateness of a particular investment or strategy will depend on an investor’s individual circumstances and objectives.

I watch very little football and almost zero of the highlights. But on Sundays when I visit my parents there’s always a game on, so I watch. I like the game. Hell, I used to love the game, enough to even consider playing another season after getting a concussion at age 14. But I was unprepared at the start of this season for just how much has changed in the way the games are broadcast and what the advertising looks like.

Yesterday I lost count of how many ads I saw for Caesars, Draft Kings, et al. When the Packers game went to halftime we put on the NFL Network and watched *highlights. As they roll through the previous games that day they get to the Sunday Night game and…the biggest graphic on the screen is the spread. Nobody said anything out loud about betting, but as they laid out what the two teams had to do to win the spread was simply there, a reminder that the only reason a fan from outside of those two respective cities would care about the game is the action they could get in on. Of course this has always been the case with these national broadcasts, but now the sotto voce implication of betting on the game has shifted to a bullhorn wielded by Peyton Manning in your living room.

*Tangential: Those highlights. were…they were not being done by professionals. The broadcasters were legitimately bad. It was like listening to minor market sports talk radio. Growing up with ESPN in the 90’s skewed our sense of how easy it is to do that job. It is evidently very very hard to make it look easy.

Don’t think the owners are ready at all Rusty

When these critically important calls are being made by Part-Time workers( because you know Billionaire owners need to save costs) and massive sports betting is going on, well that’s an obvious narrative that seems likely to be really happening.

FWIW, I too am shocked at the amount of advertising for sports gambling.

Used to be verboten, now everywhere

Warning: Following comment is tangential, possibly irrelevant, not particularly original – but all I’ve got.

My husband counsels people with actual opioid addictions and he sez: Sports gambling is the new opioid crisis.

Send in the clowns.

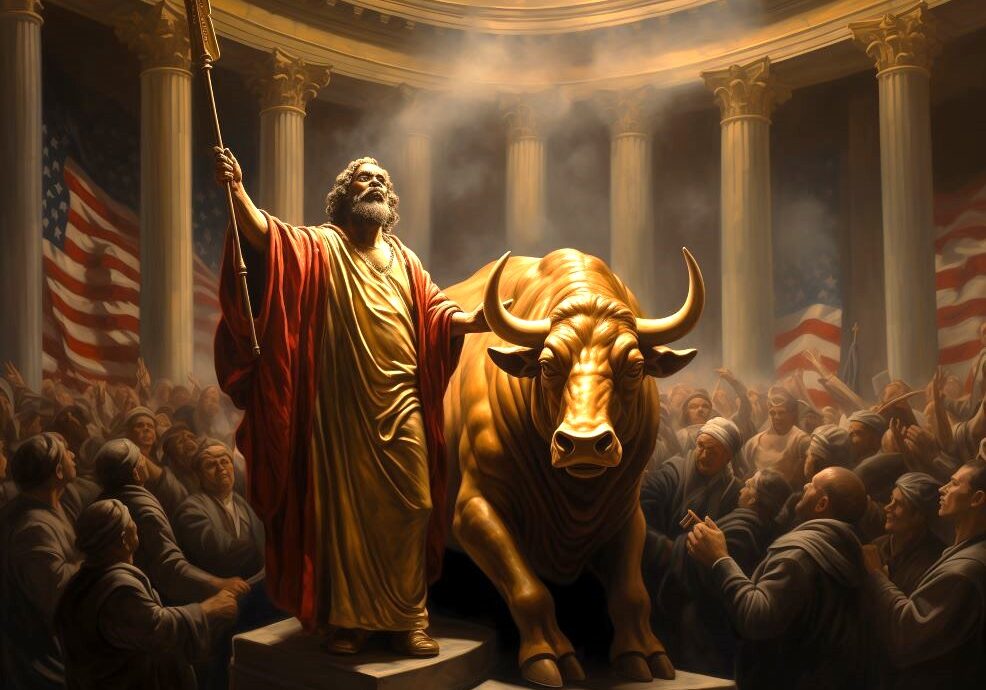

Gambling everywhere and on everything is becoming our new national pastime. The speculation layer is real. I don’t think your comment is tangential, irrelevant or unoriginal. It’s a useful observation - thanks!

No disagreement with your detailed points Rusty, and your point differential curves were very interesting, but a couple points to add some broader context.

Thanks, Hubert. Really great thoughts! My own thoughts follow based on the order of your comment:

you’ve got that right

Right on cue. It’s like they read your piece Rusty!

I unequivocally subscribe to the big picture thesis of this article, which is: the NFL’s wholehearted embrace of gambling will lead to unintended consequences that threaten its viability.

I also concur with the premise that the referees are the vulnerable target were someone to devise a game-fixing scheme, given their outsize influence on the outcomes (as Rusty demonstrated) and their meager financial compensation. This is easily remedied, however, simply by increasing their pay (and potentially by adding an incentive comp plan). Closing this loophole would not even cost that much - maybe $1m per team. Yes owners are cheap, and often foolishly so, to the point of self-harm, but there are other constituents in the value chain here - the NFLPA, the broadcast partners - who could be made to chip in.

At the end of the day, there is simply not that much money to be made in game fixing - not enough to tempt the players, or at least anybody good enough to be worth bribing. (The days of Arnold Rothstein possessing the power and wealth and Shoeless Joe needing some pocket cash are long gone. Today the eighth guy off the Miami Heat bench makes more than any gangster.). Legalized sports gambling is highly regulated. There is KYC compliance requirements and the casinos are highly attuned to irregular wagering patterns. The private (illegal) gambling market is small. No neighborhood bookie is taking $1m action on a single game. So the cost of paying the refs enough to blunt their financial motivation to fix games is by no means very expensive. If someone can pay Tony Romo $17m to blabber; they can find a similar amount to supplement the officials’ pool for guys who actually matter to the game.

Tangential: officiating in the NFL DOES suck. Not in the sense that the calls are bad or blown; but in the way officials so frequently and inelegantly intervene in the game. They are full on participants. And nobody wants to see it. As an entertainment product, pro football is significantly harmed by referee interference. If I were an owner or member of the competition committee, my top priority would be putting that genie back in the bottle.