I remember when I first knew where I wanted to go to college.

I also remember the look on my dad’s face, sitting on a bed in the Holiday Inn in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. I could tell he was struggling with whether we could manage it. It would mean taking out about $25,000 in federal loans in my name. About $60,000 in his. We had never even considered taking out loans for me to go to college before. This was more debt than the mortgage my family had taken out on our house. A campus visit and a childhood spent building up credibility as a sober-minded, serious kid later, and we would be in for 85 grand. If I could get in, I knew, I had to do it. I had earned it, you see.

No, I deserved it.

This piece deserves a thoughtful response than I have time for at the moment. All I can say right now is Wow! No, make that WOW! Rusty Guinn, you have my total respect for your masterful analysis of this issue.

Let me say again that I have nothing but admiration for the depth and rigor of Rusty’s thinking on this subject. When it comes to “clear eyes,” however, I’m more interested in discerning what’s likely to happen than expounding on what I would like to happen.

In order to anticipate how universities will respond to a challenge to the status quo, one needs to become acquainted with the concept of “joint governance.” This is the arrangement that prevails at every U.S. academic institution I’m familiar with (possibly excepting the military academies). It means administrators can only govern with the advice and consent of their faculty, and, with rare exceptions (e.g., Mark Yudof and Janet Napolitano at the University of California), that administrators are academics themselves, often holding concurrent faculty positions. Because faculty are actively involved in all of the key policy decisions administrators make, all of those decisions fall under the rubric of “academic freedom.” Yay, Academic Freedom! What this means is that Big Ed will not seriously negotiate on any of the issues Rusty mentions – not out of self-interest, mind you, but as a matter of principle. Yay, Principle! If you have doubts about this, you need only review the futile attempts of California governors of varying political persuasions to influence the policies of the nation’s largest land-grant university. As former Gov. Gray Davis noted several years ago, “academics ‘have a much longer time horizon and move much more slowly. If they don’t want to do something you propose,’ Davis said, ‘they will just slow-walk you and wait for you to be out of office.’” (LATimes, 16Jan2013)

This obduracy will suit an important group of Big Ed’s critics just fine. A quick glance at the editorial page of today’s Wall Street Journal will give you a sense of who some of these folks are. Most of the Letters section is devoted to angry parents who saved and paid for their kids’ tuition under the headline “Low Marks for Warren’s College-Debt Plan.” The lead op-ed is penned by two professional critics of academia deploring Yale’s capitulation to what they characterize as a kind of racial extortion. Betsy DeVos and company are more than willing to exploit this kind of animus, and in the process, “to destroy the village in order to save it.” With $1.6 trillion hanging in the balance, I believe it’s likely that she will be at least partially successful.

Christopher, thanks for the kind words!

I think you are right in saying that it will be very difficult to get some universities to change and recognize their role in this, in part because of the bureaucratic infrastructure that has been built around them, but even more because of the power of the rhetoric and narrative that surrounds them. Leave alone whether the schools would be willing to change - would someone be able to get elected on a platform which held them to account? Very difficult, because painting that candidate as anti-education is too easy, even if the opposite is the case.

And as you point out, the opposite ISN’T always the case. I think that it IS true that this gets complicated by a separate political dynamic - the rather stark liberal leanings of faculty and administrations at every university and the cottage industry of DeVoses who can make a living off of constant criticism of those biases. It’s a thriving ecosystem and part of the widening gyre that will make anyone skeptical of any change proposal, or at the very least equip them with the ammunition to sink it.

Alas, I don’t think that cost inflation and over-colleging rank among the top 3 issues for either party anyway. I think the most likely case is basically nothing, and the second most likely case that a GOP senate extracts some minor compromise on a Jubilee plan. Hence my belief that this is more likely to be a long, generational slog.

Gustav Kuhn shows that most people would rather believe in magic than find out the secret behind an illusion.

The breakdown seems to be getting more convoluted and complex by the second…the narrative of the bureaucracy always outlives the leadership….very salient perspectives of needed change for a better future. I talk to my college age son all the time about these types of conversations, his generation gets it better than we do…but it goes beyond status and signaling…if you do not understand and play the game you will not advance yourself to a sustainable level of quality of living…but maybe as you all propose, just start by building a village and expand from there…the larger circle may be beyond reach???

DDA: Discipline Dictates Action…Adapt or Die!

“You cannot eat like a bird and shit like an elephant”

Great conversation, thank you!

I’m not sure at what scale the smaller ‘village’ begins to obviate, or at a minimum mitigate, the need for narrative-adherence. It’s a hard question. It’s probably a much larger scale than we, or people like Lambda School, anticipate.

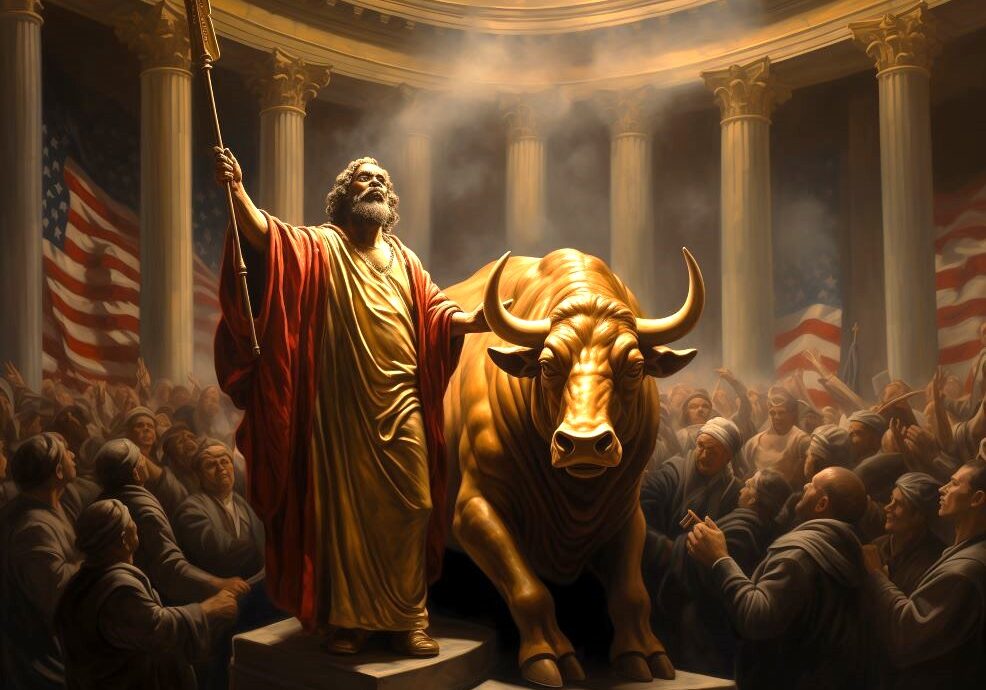

My oh my, where to start on this beast with at least 7 heads and 10 horns. Not bad from a Jew, huh? The issue of 3 moving objects is hard to tackle, but here we have many, not sure which are a cause and which are an effect. As an XKCD comic once went, “I used to think correlation implied causation, then I took a statistics class. But now, I’m not sure.” Here’s my lame attempt, after a personal note. We got our youngest son an Animal House “COLLEGE” sweatshirt for his graduation, before going on to law school. He liked being at a state university far from home, getting a political science degree, just like me.

The near-universal mantra that a bachelors degree helps you get a better job. Not so sure about that, lots of kids go to college and maybe get a higher paying job, but how many wash out because all they did was smoke pot, drink beer (I like beer) and (at least try to) have sex. Did they learn critical thinking? Can they analyze a problem? Can they change a flat tire without cell service? Maybe yes, maybe no. The series of jobs most grads will engage in may be far from whatever their degree was in, and STEM emphasis is IMHO, mostly hogwash. I’d rather hire an English Lit. major who can dissect Shakespeare than some math geek who has no social skills.

Seeing demand, many for-profit schools popped up with outrageous tuitions. Maybe because I’m a product of state schools and a year at community college and worked my way through both undergrad and law school and borrowed about $70k in today’s dollars, I have a different view than someone who attended Rollins or Stetson, or UM, Emory, etc. At the graduate level, it’s even worse at least in some disciplines. Here in Florida, the semi-guild system used to be in place. One “read the Law” for seven years under an already practicing lawyer and thereafter one could oneself out as a lawyer. Makes a lot more sense than law school today. And let’s not even talk about for-profit schools like Florida Coastal which perform “cashectomies” on their students.

The market froze up for college loans and a deal with the Devil was made if I understand correctly. Loans became the province of the federal government as a backstop and are almost dischargeable in bankruptcy. That was a recipe for disaster in itself. Could the market not have figured it out? Maybe not. Now we have tens, maybe hundreds of thousands (millions?) of grads who have come into the economy with diplomas of dubious value and hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt. The jobs are not where they used to be and pay less in some places and maybe more in others (nuclear engineers are desperately needed and with a 4-year degree start at about $100k a year, never be outsourced either).

Akin to Moore’s Law, the types of jobs change radically over short periods of time. Those coal mining jobs ain’t coming back, machines go underground, some driven by joystick controls. All those people in flyover country need to load up the wagon, like the Joads, and move to the I-35 corridor in Texas, where the jobs are plentiful. The jobs many folks had just ain’t coming back even if tariffs go to 500%. Think automation, robotics, and AI have taken away jobs? Just wait until the minimum wage goes to $15 an hour. Burger joints already have ordering kiosks, self serve drinks, and more job taking is on the way. So we have a multifaceted conundrum in the nature of the economy. Financialization of companies. Busting of unions (Scott Walker was not a college grad but he rose to become the governor of Wisconsin and oversaw the busting of public worker unions). Here in Florida, we are a constitutional “Right to Work” state. Capital has won over labor, except maybe in college education teaching, but look at the TA’s trying to unionize because they’re on $14/hr jobs, no benefits, job security. Textbook sales? What’s a book? Boeing spent billions to make planes in South Carolina, another non-union state. What a grammatical mess but every time I address an issue related to this particular thought, another comes to mind, apologies for the stream of consciousness writing.

As goofy and pump and dump huckster I think that Bill Bonner is, he made some sense in a book called "Hormegeddon’ and the premise is simple and true. Too much of a good thing is disastrous. Too much food because farmers are efficient and there are perverse economics that makes fast food cheaper, and we all get fat. Too much spent on defense, and we get into nation building (and destroying, look out Mr. Maduro, you’re next on the Chicken Hawk list). Debt is good when you get $5 in growth for every dollar spent, not so much when the marginal utility of a dollar borrowed gets 10 cents in productivity. And so it goes. We have a cause and effect relationship between education, loans, the need for and goals of a degree, the lowering of the marginal utility of said degree, people paying bribes to get their kids into such august institutions as USC, because they can’t do it the old-fashioned way, donating a building like Mr. Kushner or the Bush dynasty. Self-enforcing and reinforcing elites from Ivy league schools will always be around, especially with endowments in the tens of billions.

Ok, my rant is done for now. You have a gift along with your colleagues, much deeper than anybody I’ve been reading. Brilliant. I have a suggestion for leveling or at least budging the bubble a bit towards level: 18 to 21-year-olds must perform national service. Take your pick. Military? Peace Corps? Wildlife/parks? Teaching poor students? Picking up trash? CCA type jobs? Take your pick. That’s one reason Dan Senor attributes to Israel in Startup nation. They’re much more varied in background and politics than we are, even within the same religion. If they can do it, we can. National service forces/allows the kids to mature, take on life or death decisions and build community. Then they get on with college, or not.

Before you go to college you must serve the commonweal. Ask what you can do for your country. No senator’s son or daughter exclusions. The Kardashians must serve as well, they can be influencers from their government-issued barracks where they can live for 3 years, or flee to Paris, like Mitt Romney or London, like Bill Clinton. Stay there, good riddance. But I digress. In exchange, you get some sort of voucher to use towards education, if you want. If you went into teaching people, maybe it’s a start towards education. Drive a truck? Not so much if Elon et.al. get their way. That’s not your road, someone built it for you to get your products in and out. We can have some infrastructure rebuilt with the brains and labor of mandatory service. We would also instill some sense of community which reinforces the zeitgeist the country was supposedly founded upon. -30-

There is actually a solution to the loans problem that operates in practice - it’s called Australia.

It has a number of parts:

Universities are not allowed to charge domestic students fees directly. However universities can and do charge international students fees at market rates - Higher Education is the 3rd biggest export industry in Australia.

In Australia too there is a problem with not enough people taking up trades (ie electrical trades or construction trades) mostly because we haven’t got the policy settings right about how those things are funded and promoted - the same University! meme operates here as well to our detriment.

Yes, we have direct regulation in an industry - however I doubt very much whether the Australian people would have any appetite for changing the way the system works - we have a different attitude to government in Australia than people in the US seem to - we view it more like a vast utility that works for us than anything else. The academic community generally, including the leadership level seems to be broadly satisfied with the system.

The purpose for the comment is to point out that there are workable solutions to the issue (well the funding side of the issue anyway) which require a generational compact. It so happens that we look at inter-generational equity as well - there is a report done every 3-5 years - https://treasury.gov.au/intergenerational-report - that tries to inform the debate about these issues.

Wow, there’s a lot to unpack here, too! I think a lot is worth discussing in a Mailbag rather than just responding here, but in the meantime, thank you for your thoughts.

Another brief observation: I’ve toyed with the idea of national service. It has worked for Israel, as you point out, and I’ve met enough former IDF to know that it IS a socially unifying force. It’s worth remembering, however, that Israel has roughly as many people as Virginia, and that there are some pretty powerful reasons to believe that young Israelis really are unified on certain topics.

I have liberty-related aversion to the idea in the US, of course. Without an existential threat, I find it difficult to make a moral argument for state control of (more) of the average person’s life. But the size and diversity argument is the more challenging for me. Maybe I’m cynical, but I suspect any national service program in the US would become the plaything of the moral/policy preferences of whatever group was in power. It would more likely lead to choices between participating in overseas military adventures or environmental activism rather than something with more freedom of choice.

But I’m happy to have my cynicism about this dashed. More in an upcoming mailbag.

As a supporting anecdote, I have five kids in Australia. Four have gone to university with one more on the way next year. I have never paid a cent in contribution to their tuition, only occasionally helped with rent. The eldest is just completing her fourth degree, a second masters in clinical psychology. None of them has ever complained about their debt; it is seen as fair and manageable. Whether university is “necessary” is an entirely separate question.

So great to see this back on the ET main page. This post started family discussions on the future of education. Strange looks were directed my way around the dinner table at first. Fast forward to today, my nieces are freshman at a vocational high school. College is still in their future; but so is working after high school, or community college, or an associate’s degree before college.

Rusty, a belated thank you for this note! It had a big, positive impact on this family!

Looking forward to Ben’s upcoming note after today’s office hours. So do we all know that we all know that college is free?