Editor’s Note: this is an unedited thread from the ET Forum that I’ve republished here in close to its entirety. I’ve got a small entry on the thread; otherwise it is written entirely by regular Epsilon Theory subscribers. This is just one example of why I think that the ET Forum is the best thing on the Internet today … thousands of posts across hundreds of threads, written by truth-seekers from all over the world and all walks of life, speaking to each other with respect and curiosity. If this is your Pack, join us!

Clear Eyes, Full Hearts, can’t lose.

Steve

First, a confession: I’ve been fighting the trolls on Ben’s Twitter, and I know I probably shouldn’t do it. But they know the perfect bait for me – mostly biological misinformation, delivered haughtily (sometimes also you can catch me on a chartreuse vaccine mandate). The professor in me bites way too often.

I’ve done this enough times to draw some overarching observations (keep in mind that I am often perhaps too harsh with them, so some of this may be driven in part by that – I’m trying to work on the fine balance here ):

- The respondents have little understanding of fundamental biology and little desire and/or ability to learn more about the basics.

- The respondents have very high confidence in their understanding of biology and its sufficiency to understand anything medical

- Further, they do not actually engage with new biological information one provides in the conversation – it is either unread or tortured to say something it does not. That is, open-mindedness is low.

- Opinions of experts are routinely seen as less credible than the respondents, and there seems to be little cognitive dissonance with that.

- Respondents often report a belief that experts are compromised by bias/Narrative/conflicts of interest and therefore are not trustworthy.

- Respondents seem to believe they are free of such entanglements and, therefore, able to interpret the data correctly where the experts cannot (or will not).

Ergo, experts often have very little ability to stem the tide of disinformation. This is a challenging scenario for the dissemination of accurate information and a shared epistemology, as we have discussed. In the academy, we often encounter the opposite – imposter syndrome, in which students don’t trust their own expertise and feel unworthy to contribute. Being the world’s expert on a very, very specific topic convinces one that there are lots of specific topics where others are the world’s expert and to defer to those (e.g. I will always defer to the likes of Bill Hanage, Carl Bergstrom, and Tara Smith on epidemiology).

What I’d like to hear are your thoughts on the following questions:

- When did expertise “die” in the public’s respect – that is, when did we start to see a meaningful pushback to learning and education?

- How did it die, and who killed it? (I don’t envision this is a one-way street – experts have made messes too – cue noble lies)

- What societal forces presently keep this regime in place?

- What can we do to start chipping away at/undermining these forces?

Seems to me that figuring this out holds at least some of the keys to building a shared epistemology again, where knowledge is broadly trusted. Penny for your thoughts.

Eric

I have a book by a Spanish philosopher named Jose Ortega y Gasset called “The Revolt of the Masses” published in 1930. The main theme is that the distinguishing feature of modern society is the fact that the “masses” (as opposed to the aristocracy or some other social minority) hold social power – the power over culture and ultimately the base of political power. He says:

“The minorities are individuals or groups of individuals which are specially qualified. The mass is the assemblage of persons not specially qualified…As we shall see, a characteristic of our times is the predominance, even in groups traditionally selective, of the mass and the vulgar. Thus, in the intellectual life, which of its essence requires and presupposes qualification, one can note the progressive triumph of the pseudo-intellectual, unqualified, unqualifiable, and, by their very mental texture, disqualified…I may be mistaken, but the present day writer, when takes his pen in hand to treat a subject which he has studied deeply, has to bear in mind that the average reader, who has never concerned himself with this subject, if he reads does so with the view, not of learning something from the writer, but rather, of pronouncing judgment on him when he is not in agreement with the commonplaces that the said reader carries in his head…The characteristic of the hour is that the commonplace mind, knowing itself to be commonplace, has the assurance to proclaim the rights of the commonplace and to impose them whenever it will.”

Now, I think it’s a reasonable explanation (as any) that social changes and communications technology make the power of the lowest common denominator potent. Even more in the internet and social media age. But, this sounds a little too much like just calling all these people stupid, and though they may be stubborn, stupid they are certainly not (not all of them anyway – and, lest I get ahead of myself, I have, from time to time, shared an intemperate opinion on a subject on which I am not an expert).

I think that, besides this argument of the “lowest common denominator” you have the spectacle of policy makers being spectacularly wrong in trying to control complex systems. But even more than this, I think persistent disagreement with experts is very much about “tribalism.” I think people have an interest in pointing out and declaring which tribe they are in, and the markers are not necessarily as important as the fact that it is a bifurcated issue where people can choose sides, often with moral overtones. That is, I don’t think it is as much about the death of expertise and a devaluation of learning and education, than I think it is about people trying to find an ethical and tribal home for themselves in an era of sustained upheaval caused by technology – aided and abetted in various ways by social media and the internet more broadly.

I think as difficult as diagnosis is, treatment is even harder – the only thing I can think is that trying to create a new version of “public morals” or group ethics that values expertise and devalues “misinformation.” But, honestly, I do not have any good ideas for a “solution” as such – actually, I am not sure about the diagnosis either.

Vince

Dishonesty and the abnegation of responsibility drives a lot of it. When expert A pivots to a stance contradictory to one he previously pushed – without admitting he was mistaken and apologizing – a lot of people completely give up on him as a credible source of info. By nature, the experts most people see (Fauci, etc.) are half-politician and therefore more prone to slithering out of responsibility for their mistakes without owning up to them.

A side effect of this seems to be that if now expert B has the same message as expert A, B can be discounted even if B never pivoted.

Those extreme reactions are easier than attempting to understand the challenges the expert is facing that made them do what they did. But when an expert gets something wrong and pretends that never happened, it’s easy to categorize them as fundamentally dishonest. Fool me twice, shame on me. Once that happens, good luck gaining much of the public’s trust back.

We need leaders and experts willing to very publicly admit to their mistakes without blaming others.

Aaron

At one of my first Merrill Lynch training sessions (~1995), we were told about a study of factors that influence choosing brokers. One of the top was dress. The speaker said that when someone doesn’t understand what we do, they search for what they can understand. The conclusion was to keep our wingtips freshly polished. If you saw the client statements from that period, it’s pretty obvious that polished shoes and high commissions was viewed as more desirable than understandable investment statements with performance that revealed the theft.

It’s pretty easy to get from there to 2008.

No actual experts ever called out the racoons. And now we’ve swung so far that when the next bigger financial bubble bursts, there will not be a single economist or PhD in finance, viewed as credible by the public.

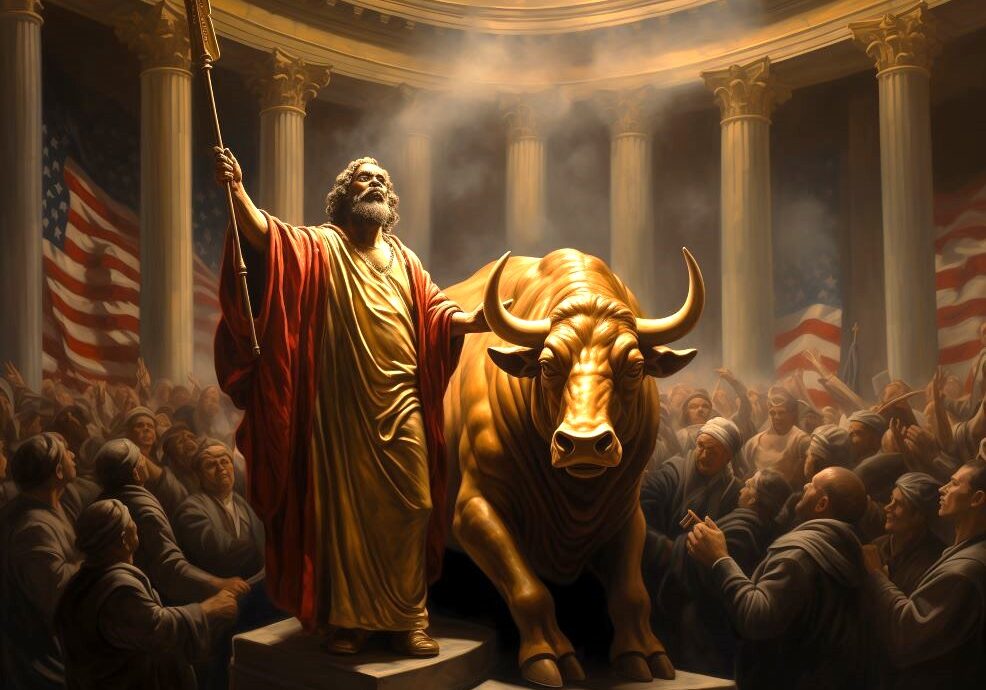

Jesus wasn’t pissed at the masses. He was pissed at the Pharisees and Saducees that mislead them. And MLK, in that Letter From a Birmingham Prison,

I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens Councillor or the Ku Klux Klanner but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says, “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically feels that he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by the myth of time; and who constantly advises the Negro to wait until a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

I’m getting a little weary of the experts pointing the finger at the masses, but not conceding that the masses have every excuse to distrust those within the same “expert circle.” Professional courtesy needs to be tossed to solve a crisis. And that’s not happening so far.

Yeah, I’ll say it. Ivermectin. Does it work? No idea. Does it kill? Nope. A doctor reminded me that we raised money for her to take a huge suitcase full of it to the Dominican Republic. Does Vitamin C or Zinc help? No idea. Are they lambasted as horse paste by the actual experts?

It’s not the masses. Well at least correcting the masses isn’t going to fix it. Either the experts right their own ship, cut out the crap and start acting like professionals, or the masses will decide that they have no use for the experts. Cause right now we’re acting on a 50/50 roll of the dice. That’s never going to happen in finance. And it’s not happening in law, when I have found 50+ court orders all fraudulently backdated and nobody will do anything. And I am afraid that it won’t happen in the medical professions.

SC

Great topic and great discussion so far. My first thought was more or less the response so well-articulated by Eric with a couple of additional thoughts.

The trend of discounting the validity of expert information and views, which has been steady for at least 15 years now, coincides with the rise of social media as a tool for the tribalism. It also coincides with a growing dissatisfaction and even disillusionment among the masses with the systems of education that are seen to have established and validated the experts. So, the anti-expert sentiment and behavior may be a consequence or by-product of a larger social transformation taking place … one that sees the masses lose faith in the core institutions of society. There are many instances where credentialed experts themselves participate vocally in the tribalism, and the masses see that because it’s on public display. This makes it easier to discount the notion of expertise altogether.

At the same time, humans have a need for experts, it’s how human society is organized and has been for millennia. When you are sick, you want a doctor and not some guy with a clever argument, to have a sword made you want a blacksmith (not a tailor), when your car breaks down you want a mechanic, etc. Humans therefore cannot reject expertise altogether and at some point the issue will naturally be confronted somehow, though it’s hard to envision presently.

Last thought, more general, is that experts often can become distinguished because of their communication skills and capability. There likely are many cases where experts would be more broadly trusted if their delivery and communication strategy were more effective. Credentials can go so far, and then communication is in many ways the key to success? Experts with a credible way to distinguish themselves from a tribalised expert within the attention span of the average human can likely be more effective overall, which involves translating expert information into simple terms that fit with the audience’s predisposed biases and can push the right buttons. That seems to just reflect what the masses have become.

An example that comes to mind is a researcher named David Shiffman who studies sharks and their roles and interactions within marine ecosystems. He is a highly qualified expert – https://davidshiffmancv.com/ – who has tried repeatedly to communicate that ecologically responsible shark fisheries should not be disfavored by policy but rather should be promoted as a global model for shark conservation. This, however true, runs counter to the mainstream narrative of “all shark killing is bad for ocean biodiversity” promoted by a far larger number of equally credentialed and qualified experts in conjunction with non-profit groups that raise hundreds of millions of dollars of their shark conservation campaigns. Is it about truth and science, or is it about publishing papers and gaining celebrity status? Is it about money? This partly how expertise loses its credibility.

‘Critically endangered sharks, meanwhile, got a tiny fraction of the attention of the better-known species, like great white sharks. They showed up just 20 times in nearly 2,000 articles.

The result of the skewed media coverage, Shiffman says, is that “a concerned citizen learning about this important issue from newspapers would be badly misinformed,” which could lead them to support policies that, at best, won’t work.’

Mongabay Environmental News – 13 Jul 20

Shark fin stories by major media ‘misleading’: Q&A with David Shiffman 1

Lawrence

Read Rusty’s “ First the People”

It was written a year and a half ago , but could be rewritten today with many many more examples of betrayals of the publics trust.

DY

Respondents often report a belief that experts are compromised by bias/narrative/conflicts of interest and therefore are not trustworthy.

Respondents are basically reporting to you existing facts.

Respondents seem to believe they are free of such entanglements and, therefore, able to interpret the data correctly where the experts cannot (or will not).

That’s the difference between the trolls and good faith skeptics (a class with whom I would nominally identify). I’m mistrusting of the Expert Class TM because I have watched their actions and listened to their words. But at no time during my life have I assumed that I’m somehow magically free of the same sort of chains that bind others.

How did it die, and who killed it?

It was a suicide. Cable news assisted.

What can we do to start chipping away at/undermining these forces?

I have no interest in helping experts undermine those forces. Those forces, as flawed as they are, exist as a counterweight to the (at best) bloviations and the (at worst) outright lies. Your faith in the gormless blob of technocracy is not something I share.

Seems to me that figuring this out holds at least some of the keys to building a shared epistemology again, where knowledge is broadly trusted.

You say “again” as if this were some condition that once was present but that vanished overnight. When precisely was this? As a late Gen-X/early Millennial I’m straining to remember a time when I trusted any of you adults. After witnessing one of my college professors steal a Penthouse I sort of understood that the tweed jackets and the old Volvos were affectations and were unrelated to any sort of underlying expertise. A lifetime of being inundated with the advice, protestations, and warnings from Experts TM has lead me to be naturally mistrusting. It’s been perhaps the most valuable thing I’ve ever learned.

T

George Friedman has written a couple of essays regarding experts and expertise and if I am correct in my recollections he attempts to draw a line from post WW II USA where a reliance on experts and expertise became a central feature of American culture (esp. political culture) and the present where the narrow view of experts is less tolerated.

I can also refer you to “The Revolt of the Public” by Martin Gurri. Elites losing ability to control narrative given the wider access to information.

Seems like the “Golden Age of Expertise” may have gone the way of the “Golden Age of Air Travel”.

Ben Hunt

I think that expertise became a hopelessly tainted and more than somewhat evil concept with the invention of “social science” as a thing. And I say this as a card-carrying “political scientist” (a phrase that was invented at Princeton in Woodrow Wilson’s day). The idea that there is a scientifically correct policy solution for any social ill, and that this solution can be identified by the best and the brightest through mastery of a certain body of knowledge, is what creates Science with a capital S. It is the ruin of the world. Seriously.

Steve

Thanks, all, for the very thought-provoking responses – I am going to chew on them and see if I can contribute anything helpful back. I will admit they aren’t super encouraging, but they do tend to confirm my priors – that the goose is pretty much cooked until, at least, we go full-on Fourth Turning (maybe even beyond that). Please keep the comments coming – this isn’t in any way intended to cut them off but rather to stimulate more.

I do want to make a distinction and add a couple more questions for you all. It’s my intention to ask not about Science (capital S, or perhaps ScienceTM), but about science (small s). I’m actually not talking about – nor advocating, heaven forbid – technocracy (i.e. the Smarts should rule) or even American apple-pie meritocracy (if it even exists). In fact, I am not talking about politics or policy at all. What I am asking about is really epistemology – how we know what we know about the world, and to what extent we trust new information that is not personally verified (meaning, you didn’t generate it or oversee its generation).

If you will, I’d appreciate your thoughts on the following questions (answer as many as you have interest in and time for – I know this is a heavy ask):

- Do you believe that the data coming out of scientific enterprise is generally accurate (meaning, actual measurements to the limits of technical ability)? Would you generally believe the data coming out of my lab (or another scientist you know)? Do you think the public, in general, agrees with your assessment (about the data in general question, nobody in the public even knows who I am)?

- Do you believe that published/released scientific data are generally interpreted correctly (or, at least, in good faith)? Would you generally trust the conclusions of our papers, even if you did not understand how the data were generated? Or, rather, would you only believe those conclusions you felt you could interpret from our data (or other data) on your own? Do you think the public generally agrees with your assessment?

- In the thought experiment above, did your assessment of trust in new scientific knowledge “in general” differ in any way from your trust in the work of a scientist closer to you? Does it matter to you whether the scientific knowledge is generated by someone “in your community,” broadly defined?

- In general, do you tend to weight the opinions/interpretations of people with lots of experience in a field more heavily than a relative newcomer? If so, would you feel the same way if you were the newcomer?

THANKS!

CH

#1 I don’t believe your class commits actual fraud. I believe you accurately measure whatever it is you’re trying to measure. I believe the bias in the peer review system would self-correct for this.

#2 I believe it’s interpreted generally correct. I believe the bias in the peer review system would self-correct for this.

#3 No difference when it comes to something they actually measured/studied/interpreted. Vast difference when it comes to something less rigorously and academically studied.

#4 Yes. Yes.

Here’s the problem as I see it with our research class, and why it’s not trusted as much as it used to be. It’s not so much how accurately you measure, or interpret the results. It’s more about what you measure. I believe what you measure is largely a reflection of the inherent bias in the system. Whether it’s because of political/institutional bias, or a financial incentive, I believe there is a lot of bias in the determination of what gets measured and reported.

Eric

(1) I think: that what I think is meaningless, because I have no reason to not trust you, and, seeing as you’re posting on here, I would be inclined to trust you… More to the point, I think the general public, aside from not knowing who you are, would not even begin to think or not think about the potential accuracy of the data from your lab.

(2) I think most truly scientific enterprises are so esoteric, there is no way for lay people to understand them, just to possibly place them in a context of things they really do know. So, I don’t think it is capable of being interpreted correctly because it must always be filtered through some analogy or explanation that dumbs it down. If I were an expert in the field, well, it would be readily apparent the takeaways from your methodology and data.

(3) I think direct trust will always be more powerful than authoritative statements. So hearing something from someone you trust is always more powerful, regardless of accuracy.

(4) I think most people do tend to side with expertise, unless there is a more powerful social factor that degrades that trust.

I tend to think that the foundation of these questions is difficult to assess accurately. That is: how quantifiable is it that we have degraded expertise over previous eras? I think this may be a case of observing the aberrational 20th century as the “base case.” The early and mid 20th century had, historically, I think, an unusual amount of social, political, and cultural power centralized – along with some scientific advances that genuinely, massively improved everyone’s lives. The introduction of antibiotics was not something that could be broadly disputed as being beneficial or not to people, a polio vaccine was a miracle, electrification improved the drudgery of life for many of the world’s poor. So maybe what we want is this halcyon era, that was defined by the horrors and wonders of massive centralization and trust in authority. But even then, there was a horror at the necessities of say, the scientific advancements of modern war, or the creation of massive bureaucracies (reading memoirs from soldiers in WW2 often reads more like Catch-22 than Saving Private Ryan). So I don’t know how high trust was in experts, actually, in 1940, or 1820, or 1540.

I think it is very difficult to see exactly where we are, from Walter Lippmann’s “Public Opinion”:

Looking back we can see how indirectly we know the environment in which nevertheless we live. We can see that the news of it comes to us now fast, now slowly; but that whatever we believe to be a true picture, we treat as if it were the environment itself. It is harder to remember that about the beliefs upon which we are now acting, but in respect to other peoples and other ages we flatter ourselves that it is easy to see when they were in deadly earnest about ludicrous pictures of the world. We insist, because of our superior hindsight, that the world as they needed to know it, and the world as they did know it, were often two quite contradictory things. We can see, too, that while they governed and fought, traded and reformed in the world as they imagined it to be, they produced results, or failed to produce any, in the world as it was. They started for the Indies and found America. They diagnosed evil and hanged old women. They thought they could grow rich by always selling and never buying. A caliph, obeying what he conceived to be the Will of Allah, burned the library at Alexandria.

In my first reply, I quoted a book published in 1930, where it was already noted that people were no longer trusting of experts, well, who knows what we will think looking back in 30 years. I think that the fundamental problem is not one of “trusting experts” but of more powerful social incentives framing expertise as trustworthy or not or good or bad.

I am not qualified to say what it looks like from inside a scientific or academic profession, perhaps creating a sense of scientific answers in places where there can only be a scientific process (which I think is what Ben Hunt was saying) has caused a gulf to open between what people have said and promoted and what is “true.”

I don’t think this credibility gap is closed by the reverse process of its opening though. We may be looking at it wrong, in that, instead of getting people to trust expertise, we simply dissuade expertise from being involved in social conflict – or, more likely, we accept that expertise will never be without its biases and crises of replicability, and cannot be accurately explained to the public. For instance, OK, so Fauci lied about masks, but, would he have more credibility with “conservatives” or anti-maskers or whatever group reviles him if he hadn’t? He may have become less of a villain, but his expertise would not be trusted by this same group regardless.

Again, from Walter Lippmann:

For there is an inherent difficulty about using the method of reason to deal with an unreasoning world. Even if you assume with Plato that the true pilot knows what is best for the ship, you have to recall that he is not so easy to recognize, and that this uncertainty leaves a large part of the crew unconvinced. By definition the crew does not know what he knows, and the pilot, fascinated by the stars and winds, does not know how to make the crew realize the importance of what he knows. There is no time during mutiny at sea to make each sailor an expert judge of experts. There is no time for the pilot to consult his crew and find out whether he is really as wise as he thinks he is. For education is a matter of years, the emergency a matter of hours. It would be altogether academic, then, to tell the pilot that the true remedy is, for example, an education that will endow sailors with a better sense of evidence. You can tell that only to shipmasters on dry land. In the crisis, the only advice is to use a gun, or make a speech, utter a stirring slogan, offer a compromise, employ any quick means available to quell the mutiny, the sense of evidence being what it is. It is only on shore where men plan for many voyages, that they can afford to, and must for their own salvation, deal with those causes that take a long time to remove. They will be dealing in years and generations, not in emergencies alone. And nothing will put a greater strain upon their wisdom than the necessity of distinguishing false crises from real ones. For when there is panic in the air, with one crisis tripping over the heels of another, actual dangers mixed with imaginary scares, there is no chance at all for the constructive use of reason, and any order soon seems preferable to any disorder.

It is only on the premise of a certain stability over a long run of time that men can hope to follow the method of reason. This is not because mankind is inept, or because the appeal to reason is visionary, but because the evolution of reason on political subjects is only in its beginnings. Our rational ideas in politics are still large, thin generalities, much too abstract and unrefined for practical guidance, except where the aggregates are large enough to cancel out individual peculiarity and exhibit large uniformities. Reason in politics is especially immature in predicting the behavior of individual men, because in human conduct the smallest initial variation often works out into the most elaborate differences. That, perhaps, is why when we try to insist solely upon an appeal to reason in dealing with sudden situations, we are broken and drowned in laughter.

I think it is impossible to directly address the issue of “trust” or “belief” in scientific processes or expertise without addressing the broader dislocations and fears of the era. That is, in order for people to trust a scientist, they have to trust their neighbor first, because it’s not actually about anti-intellectualism and the failure to make good decisions and predictions, it’s about having faith and foundation in communities. IMO anyway.

I really am sorry for the length of this reply, just wanted to flesh out my (probably contradictory, if I were to reread) views on the subject at hand, and also, I like Walter Lippmann…

DY

What I am asking about is really epistemology – how we know what we know about the world, and to what extent we trust new information that is not personally verified (meaning, you didn’t generate it or oversee its generation).

I want to give your other questions some serious thought, but for now I have time to address this one bit. Have you ever seen the Netflix show Rotten? They should have titled it Everything You Enjoy is Actually Evil, it would have been more accurate. It’s basically an exploration of how common things—in this case various foods—cultivate a culture of evil and violence within the ecosystem that produces them. Mexican cartels and avocados, Chinese Uighur slaves and garlic, Chinese Uighur slave laborers and wine (common theme over there), etc. The point is that what we thought we knew of the world was always some half truth mixed with bullshit and wrapped in a thin candy coating. Maybe there’s some value in the collective population acknowledging that we’ve been conned and starting over, so to speak.

T

Hi Steve

I think it is hard to paint this black and white. Science as practiced if defined only as research using the scientific method ie reproducible results yields quantifiable answers that can be peer reviewed. So overall skullduggery by the scientific community, naaah – hard to see.

But all this does not happen in a vacuum and not all science is practiced as rigorously as it should be and as the same in other professions charlatans exist and good people get pressured by folks with agendas. So yeah, you should be circumspect in what you buy into.

Smartest man I ever knew worked for 11 years trying to reproduce experiments being published by scientists working in what was then the USSR. Found plenty papers that did not pan out.

Perhaps what we are experiencing is push back from being told what is best for us by experts.

If you are told something is a scientific fact, and therefore unassailable, and you are asked to swallow the line of reasoning coming out of that fact hook , line and sinker and it does not sit well with you, for whatever your own personal reasons are, then you attack the messenger and his method that says “you have to accept this”.

I find Dale Carnegie to be a good source of what other parts of human nature come into play besides our purely rational selves.

Having said all that the anger and hostility that exists in discourse these days makes opening the mike a precarious proposition and “Good on ya mate!” for trying for clarity on something that seems to be on your mind.

SC

The public has little to no idea how to interpret what scientists tell them and so the naively trust what they’re told. This trust is systematically abused on a regular basis and the more funding behind misinformation campaigns claiming to be “backed by science” the more effective they’ll be in convincing people of things that are not true.

Brandolini’s law states that, “The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude larger than to produce it.”

“So, not only are there many opportunities for information to be misconstrued, but there is also a financial incentive to do so. More “interesting” results beget more funding, more “troubles” beget donations, and more hyperbole begets pageviews. Nuance, a crucial part of science, is cast aside.”Sustainable Fisheries UW – 22 Feb 21

From fishery science to fake news: how misinformation about the ocean evolves 1

Scientists have successfully planned their research and publications to achieve targeted deception over long periods of time … this doesn’t happen by accident, it’s deliberate. Some Pack members probably watched the strategically deceptive documentary Seaspiracy on Netflix. Many scientists have spoken out regarding how insane this is.

“So how did 10% get inflated to 40%?

In 2009, three people working for NGOs (World Wildlife Fund & Dorset Wildlife Trust) and one unaffiliated person decided to write a paper arguing that the definition of “bycatch” needed to be redefined to include ALL catch from unmanaged fisheries. From their paper:

The new bycatch definition is therefore defined in its simplest form as: “Bycatch is catch that is either unused or unmanaged.”Sustainable Fisheries UW – 3 Apr 21

The science of Seaspiracy – Sustainable Fisheries UW 2

Here’s another part of the long term commitment to spinning falsehoods, in this case regarding the projected impacts of Marine Protected Areas.

“What’s strange in this story is how the conflict of interest intersects with the science. The conflict of interest was apparent immediately upon publication, but it wasn’t until major problems in the underlying science were revealed that an investigation was launched, and the paper eventually retracted.”Sustainable Fisheries UW – 8 Dec 21

Retraction of flawed MPA study implicates larger problems in MPA science 1

The data, interpretations and published statements of the scientific community cannot be viewed as trustworthy across the board, there are mountains of evidence to support skepticism, but the fact is that most of the public believes anything that suits the stories they like the most or that suit their own views and objectives.

The fact is that policy is often driven by public perceptions, so if you want policy that works in your favor, invest in the the right “science” and PR campaigns and you’ll get your way. In ET speak it’s Scientific Raccoonery, and the raccoons are winning! Paying attention to the actual truth is important for perspective but it’s equally or more important to pay attention to the false truths because those are likely to drive policy direction and public perceptions (and associated risks and opportunities). None of that is going to change any time soon.

Patrick

What a great thread! Rather than trying to add to it with some banal insight that barely moves the needle I was most moved by Eric’s reminders of the limits imposed by human nature. I encourage everyone to spend time with Mark Twain over the holiday quiet.

Favorite quotes that are brutal reminders in this struggle:

“Never argue with stupid people, they will drag you down to their level and then beat you with experience.”

“I have never let schooling interfere with my education.”

“A half-truth is the most cowardly of lies.”

“Get your facts first then you can distort them as you please.”

“A lie can travel half way around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.”

“The man who does not read has no advantage over the man who cannot.”

“The more I learn about people, the more I like my dog.”

“If you don’t read the newspaper you are uninformed. If you do read the newspaper you are misinformed.”

There are hundreds more, not dimmed in relevance by the passage of decades.

“Too much of anything is bad, but too much good whiskey is barely enough!”

SC

Interestingly, Lippmann was a close collaborator of Edward Bernays on the use of propaganda for winning elections, which worked just as well as it had for Bernays’ clients in a purely commercial setting.

“What Bernays’ writings furnish is not a principle or tradition by which to evaluate the appropriateness of propaganda, but simply a means for shaping public opinion for any purpose whatsoever, whether beneficial to human beings or not.

“This observation led Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter to warn President Franklin Roosevelt against allowing Bernays to play a leadership role in World War II, and his colleagues as “professional poisoners of the public mind, exploiters of foolishness, fanaticism, and self-interest.”

Today we might call what Bernays pioneered a form of branding, but at its core it represents little more than a particularly brazen set of techniques to manipulate people to get them to do your bidding.”

The manipulation of the American mind: Edward Bernays and the birth of public… 5

Jeff

I believe it started with law schools & their method of debate; to “win the debate” regardless of how it was done. This mindset was then transferred to politicians (most of them being lawyers) & then to debate of controversial issues on news programs. It was from this that everyone learned how to do it.

Just my opinion, but something I have thought about over the past decade.

Eric

Highly recommend Lippmann’s Public Opinion, it is in the public domain and a quick read. Stylistically it is great prose writing – it presupposes some knowledge of the First World War, but a lot of it is still just as relevant. He kind of calls for the creation of a CBO at some point, or some kind of “scientific” measure of legislation, and it’s interesting to see the appeal of a less cynical philosophy, and to see what’s changed. I think, 100 years ago, if they were to predict a pandemic like COVID in 2020, they would’ve assumed that we would have united as a country, just as under war conditions. The opposite has occurred, it has widened the fissures, IMO.

One other thing about the book, I think it pretty well punctures the idea of: “show me the incentives and I’ll show you the behavior.” Not so much because it’s not true, but because “incentives” are inscrutable and discrete from one person to the next.

SC

Thank you for recognizing Bernays’ significance, and the value in examining his career. I would call him the original architect of today’s consumption-oriented society. He has mastered the art and science of managing what he termed a “bewildered herd” and proved repeatedly his thesis that by appealing to the deep unconscious desires of people you can get them to consume things that they don’t need, even at the expense of things that they do need. Following this principle, Bernays founded modern branding that is applied in nearly every product and service category, and working with Walter Lippmann it was applied directly to politics.

Because of having thought deeply about Bernays and his doctrine (and its tremendous success) I’ve adopted the pursuit of understanding what drives people consume goods and services. In terms of this thread, I wonder why members of the general public are interested in consuming scientific information. I generally believe that discretionary consumption is based on either a desire for sensual pleasure (e.g. indulgent dining experiences) or because they believe they will gain competitive advantage in some way (e.g. elevated social status, improved social standing within family or social circle, etc.), and I wonder what motivates members of the public to consume social media (be on Twitter) and engage in arguments or mindless rants about scientific information. I think it motivated by a desire for status within one or more social circles, and likely are motivated almost entirely by a confirmation bias – they truly don’t care about what is legitimate or true as long as it holds up within whatever social circle they’re aiming for status within. In response to this demand, the “market” provides a steady stream of material that doesn’t really need to be legitimate at all in order to be marketable, and so the needs of the bewildered herd are met in a manner that yields profits.

T

There are so many flavors to this I think it is hard to generalize. I have lost a sibling to it. A very successful sales person in high end beachfront real estate for 40 years. Extremely bright and articulate, used to being the center of attention of clients. Started out with a child that was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease and dove into the Ipad and soon was finding fault with the Mayo Clinic’s treatment advice. Within 3 years it spread to all topics of discussion. One thing about a science reference it can be used as a “third party” that supports a line reasoning without being present to provide context or actual meaning. Remember the comeback line “oh I see that you’re also a doctor”.

Internet access pours gasoline on the fire.

As this was a big loss for me ( only two siblings) I started paying attention to other relationships I have that had some of the same traits and a couple of things that seem typical for many of these. The hope was to gain understanding and be able to determine which relationships I had a chance to be more successful in holding together than I had been with my sibling and which I was better walking away from. The couple of things I noticed was:

Its a “win the day” type of thing.

No problem holding two seemingly contradictory positions simultaneously.

Stumbled across a list of communication traits in my fiction reading that rang true for me. There is probably some confirmation bias on my part going on here.

- Speech is aggression.

- Every utterance has a winner or loser.

- Curiosity is feigned.

- Lying is performative.

- Stupidity is power.

Brian

I find this line of thinking very interesting. So much could be discussed.

“Lived experience always outweighs expertise. Nobody can argue with what you feel to be true.” Ironically expertise and experience look to be from the same root.

Is expertise actually dead in the public’s respect? Or is that a narrative espoused by a few but magnified by the many on social media? Does that mean all experts, every last one of them? Or just very specific ones where (dis)honest mistakes may have been made? What is the exact line where someone officially becomes an expert in something and hence is no longer trustworthy? Bachelors, Masters, PHD?

I expect one could list a multitude of reasons why people suspect expertise. A big one might be that some percentage of any population is generally innumerate while also having an incomplete understanding of the scientific method. (The method BTW that has led to the very civilization(s) we currently live in today)

As Keynes once said, “When events change, I change my mind. What do you do?”. Spoken like a scientist. Very few things in life are 100% (death/taxes) but homo sapiens, in general, aren’t well built to change the flow/direction of their mind once an idea gets snagged up in there. Confirmation bias and all that. Regardless, that is what science tries to do. Observe, hypothesis, test, conclude, refine. Imperfect? absolutely! Got a better replacement? Let’s hear it. (besides conspiracy theories et al)

We humans also prefer commitments and consistency (a la Cialdini) and hate change so we’ll oftentimes throw under the proverbial bus those that do not exhibit these traits. e.g. unkept political promises. So maybe a world of accelerated change is contributing.

But I do not buy into the idea that “expertise” is dead. Our whole world is built on expertise. I don’t repair my own car, I don’t do surgery on myself, I don’t run the internet etc… There are many and myriad things we ALL defer to someone else’s “expertise” and the proof is in our actions. I believe it is just that we are encountering “disaffected bias” (just made that term up) in that we mostly read comments from the aggrieved and so place more weight than is appropriate there.

Interestingly, respondents who say they know better than the “expert” in some field. Assuming that was true, doesn’t that then make them the expert? and doesn’t that then mean they no longer know what they are talking about because they are now the “expert”? What a rabbit hole to go down that is.

I think anyone that truly believes that all experts are fools or liars etc… would have to be a literal hermit and so logically we wouldn’t hear from them because they wouldn’t have internet, phone, electricity etc because they wouldn’t trust the “experts” who could provide them with these things.

Steve

Y’all have done some amazing work here, Pack – and I greatly appreciate what you’re contributing. I intend to go through this in some more detail, because I think a number of you have raised some really interesting points that provoke some thoughts. But for now, let me give you a little of the view from the Ivory Tower, and perhaps that may stir up some thoughts that suggest some solutions going forward. I’ll caveat first by saying that everything here is from the natural sciences perspective – I imagine things are very different in the social sciences and humanities, and I am guaranteed to screw up if I start talking for them. From here on our, I’ll simply call the natural sciences academics “The Academy” for simplicity (and brevity).

Here is why your feedback is so helpful – The Academy, by and large, knows it has a credibility problem, but it does not know it has this credibility problem. It is used to dealing with those who believe in a young or flat Earth, for example, or near the furthest extreme, “the Moon landing was faked.” However, these are people who generally believe the data science produces, but reject its intrerpretation. Meaning, these folks still believe that the measurements are real and the scientific process works, even if scientists reach erroneous conclusions from otherwise correct data (fill in the blank as to why this occurs; I frequently hear that scientists start with the wrong suppositions, which leads them to make conclusions that are incorrect). You can see this even in the ways in which these competing movements are named, e.g. “Creation Science,” for example, presupposes at least that the scientific method is trustworthy. It is a movement designed to run parallel to and, over time, outcompete the scientific dogma, but within the framework of scientific process, displacing the previous paradigm. Thus – argument amongst these conflicting groups stays within the realm of shared principles and data, even if interpretations differ.

I think my colleagues would be very surprised to hear the prevalence of the types of concerns advanced in this thread by some very smart people, as they are, in general, outside the scientific process itself. I think the reason for the surprise has, at least a little but probably more, to do with academic hubris along the lines of thinking that 1) the Enlightenment tradition of rationality is obviously the best way to organize society, and 2) teaching of the scientific method has penetrated through society in such a complete way (especially given modern STEM initiatives) that the people who don’t get/embrace it are in some way defective (and can be ignored). Ironically, I think it’s this type of thinking that has gotten us into this mess – as the modernism of the Enlightenment penetrated through society (perhaps reaching its zenith somewhere in the 50s?), perhaps building the narrative foundation for modernism has been neglected and the objectors have been sidelined as “uneducated.” In many ways, you could describe the utility-based arguments (does the expert’s addition to society improve peoples’ lives?), the experience-based arguments (does the expert’s contribution line up with my lived experience?), and the authenticity-based arguments (is the expert consistent in her/his opinions (or even as a whole field – see the tragedy that nutrition research has become in its vacillations and tracebacks) over time?) could probably be best described as post-modern. In The Academy, I hear almost no discussion of these ways of viewing reality, as it’s populated, probably completely, by intellectual modernists. I’d think it would be a very challenging career choice if one weren’t a modernist – scientific research is brutal enough when you are very convinced in suitability of the methods to generate new knowledge.

In retrospect, this is why I went mid-thread to asking about everyone’s perspective on whether 1) data and 2) interpretation are trusted from strangers (i.e. relying on the credential (usually a PhD) and position to suggest trustworthiness) and 3) whether relationship is important (meaning that other types of trustworthiness can come into play) in the process. If data (A) and interpretation (B) are trusted broadly, then A+ B = conclusions (C) and these should be trustworthy. But this is a modernist way of thinking. What I’ve heard so far is generally that data and interpretation are generally trusted – sure, there are some bad apples, but there’s no coordinated malfeasance among the scientific expert class. But A + B doesn’t necessarily equal C (at least with respect to recommended applications of those conclusions) for a diversity of reasons advanced above (previous noble lies, changing positions, obvious conflicts of interest). That is to say, the conclusions are distrusted often before data and interpretation are considered. In some cases, the result is simple skepticism – a “prove it” agnosticism – and in some other cases, to provide a retrospective rationale for the distrust, data (“COVID case/death counts are untrustworthy because hospitals are incentivized to falsely report”) or interpretation (“with COVID, not from COVID”) are impugned. That is to say, in the second case conclusions that differ from mine/my tribe’s must be built on faulty data or interpretation, and an endless series of examples can be trotted out as rivaling evidence is provided. No data or interpretation that disagrees will even be really considered.

This is a very hard place to recover from, because it’s personality-, community-, and trust-driven rather than data-driven. So how does one get an audience for the data and interpretation that experts generate? How do we start to repair the foundations so at least we can agree that the measurements are true, regardless of what your tribe or my tribe says? And, then, can we begin a conversation there? Is this something we can use the blockchain to help do somehow in a trustless way? Is there a way to build small, secret bridges across the Widened Gyre in which we simply agree that the data are real (even if we draw different very conclusions from them)?

Just spitballin’ here – this is something that breaks both my brain and my heart. And I’m eager to be part of whatever feasible solution there can be – but I think I don’t see the real lay of the land well enough from the Ivory Tower to do that.

The speaker said that when someone doesn’t understand what we do, they search for what they can understand. The conclusion was to keep our wingtips freshly polished.

This may be the crux of it, or close to it. Expertise in lots of fields used to be lots closer to the public’s understanding. For example – the Hershey and Chase paper which demonstrated once and for all that DNA, not protein, was the genetic material was published in 1952. That experiment involved a blender as part of the scientific apparati used to demonstrate this. An educated non-expert could certainly have read and understood that paper (here, if you want to check it out: https://rupress.org/jgp/article-pdf/36/1/39/1240738/39.pdf). Today’s biology? No way. The techniques have layered upon themselves, as have the concepts. For the majority, to accept the modern science on an important point is no different to belief in magic – “I don’t understand it myself, but I trust the wizard.” And that may be the problem – the wizards are turning out less to be Gandalf and more to be Saruman. And, in turn, more and more people aren’t trusting their magic.

Yeah, I’ll say it. Ivermectin. Does it work? No idea. Does it kill? Nope. A doctor reminded me that we raised money for her to take a huge suitcase full of it to the Dominican Republic. Does Vitamin C or Zinc help? No idea. Are they lambasted as horse paste by the actual experts?

The “horse paste” part is an interesting phenomenon. As far as I saw, the people who labeled it such tended not to be the actual experts – they were supportive non-experts (including many journalists). In other words, the goal seemed to be to support the expert opinions not rationally but by denigrating the fringe opinion (there are, of course, some experts who support ivermectin).

It’s not the masses. Well at least correcting the masses isn’t going to fix it. Either the experts right their own ship, cut out the crap and start acting like professionals, or the masses will decide that they have no use for the experts. Cause right now we’re acting on a 50/50 roll of the dice.

I think this describes the viscerality of the vicious cycle we are in very well, which both “sides” are involved. Expert failure → public distrust → trust in self/tribe → perceived expert/public failure (depending on which side of the fence you’re on) on the one side and Expert failure → double down rather than admit it → denigrating opponents → perceived expert/public failure. I say perceived the second time because it may not matter whether the expert is actually wrong a second time – if the expert’s opinion does not line up with the individual’s (“fool me once”), it may be perceived as a failure (this is how we get family members breaking doctors’ noses over how they’ve treated their family with COVID). Once the masses decide that their/their tribe’s position is correct and the experts are wrong, how can the experts right the ship? We’ve adequately demonstrated that further data/outcomes won’t do it en masse, at least not over short time scales. If you’re right, and I think you are, that otherwise “the masses will decide they have no use for the experts,” that is truly a terrifying place – on the medical side, for example, that’s every C high school biology student for him or herself in the middle of a pandemic, and the snake oil salesmen will make bank.

That’s the difference between the trolls and good faith skeptics (a class with whom I would nominally identify). I’m mistrusting of the Expert Class TM because I have watched their actions and listened to their words. But at no time during my life have I assumed that I’m somehow magically free of the same sort of chains that bind others.

Interesting distinction between trolls and skeptics, but I think the issue here is that it is very challenging to see the blind spots in one’s own thinking, which is where we need others (including experts). Either one is humble enough to be open to correction from others or one is not; this seems to be a better distinction between the two to me. In The Academy, one of the highest virtues is self-skepticism (you get this knocked into you early – if you are not ruthlessly skeptical of your own work, others most certainly will put you in your place). This is largely why we have imposter syndrome in our students. Unfortunately, I don’t see a lot of self-skepticism out there in the culture.

You say “again” as if this were some condition that once was present but that vanished overnight. When precisely was this? As a late Gen-X/early Millennial I’m straining to remember a time when I trusted any of you adults.

By “again,” mostly I mean in reference to my Boomer parents and in-laws. The most obvious example for them is medical advice – all 4 of them go to the doctor regularly and follow doctors’ advice religiously. They trust the expertise of the medical system to care for them. My generation seems to get as much or more health information from social media influencers as from MDs. That’s not to say that MDs are always right – they profoundly are not – but the difference here is burden of evidence on care. There’s also a really different view of individuality vs. similarity. The MDs tell you that people are fundamentally similar and can be treated in the same way, because the randomized clinical trials did not – and cannot – account for fine individual differences in outcome. My generation focuses on individuality and self-experimentation (“if it works for you…”) – this is a fundamentally different view of how to generate knowledge on self-care. Neither are exactly right and both have value – in the first case, you get population-level improvement with variable impacts across individuals that you shrug off. In the second case, you never have a “control” you to compare against – and can never really attribute causation to anything. The point here is that something is different.

Based on your radiocarbon dating above, this puts you and I at roughly the same age. D-Y, I think the thing here is that we now are the adults. My view is that we have to bequeath something to future generations beyond skepticism of their elders (otherwise, should they not be skeptical of this advice?).

After witnessing one of my college professors steal a Penthouse I sort of understood that the tweed jackets and the old Volvos were affectations and were unrelated to any sort of underlying expertise.

Sorry you experienced this moral failing of someone you trusted – but this is a rather odd conclusion to draw, unless this was an ethics professor. The tweed jackets and Volvos certainly are a culture rather than related to expertise – but the underlying knowledge and skill is likewise unrelated to the theft you experienced. All experts are humans as well – with their various fortes and foibles, which are often unrelated to each other. There are plenty of reasons to doubt expertise without totalizing experts.

Really appreciated that you responded down-thread, and I’ll engage there on those pieces. But this part seemed substantially different, so wanted to make sure the thoughts got put in the right places here.

DY

The tweed jackets and Volvos certainly are a culture rather than related to expertise – but the underlying knowledge and skill is likewise unrelated to the theft you experienced.

No, it was more of a funny anecdote meant to get a chuckle or two. But it was also an incident that lead me down a path of skepticism that from there out did not disappoint. That path included a detour in which a Dean had to apologize to me for one of his professors and her bizarre behavior wherein she targeted me for removal from the school over an allegation of plagiarism. I had used an improper format for my works cited page and she deemed that to be tantamount to not identifying my source. This was considered by the Dean as one of the dumbest and most petty things that had ever landed on his desk and she was forced to give me a half-assed apology. It was then that I realized that lots of people care about having dominion over you and everything else—whether it’s the law, a code of conduct, or even a social contract—are just means to that end. The flight attendant who’s yelling at you to pull your mask over your nose doesn’t care about the mask, she cares about being able to tell you what to do. The last two years have weaponized that instinct and it has spread far beyond the control of our fragile, polite society. That Experts TM were the first to arrive at that party is not surprising nor is it their fault. We gave them that power and they really don’t want to give even a shred of it back. And THAT is ultimately what this is about, on its most basic level.

Steve

Thanks very much for this.

At the risk of reducing your confidence further, with respect to #1 – peer review doesn’t really cover data authenticity and accuracy, except in rare cases where data are put in public repositories (like raw sequences, or peptides). That is to say, when I review a manuscript I have to accept on faith that the authors actually got a measurement of X with Y standard deviation. This is where we all rely on the culture of objectivity and repeatability in scientific research and, yes, we all know that there are bad actors out there who don’t follow these internal rules. But the vast majority of us are committed strongly to making sure the scientific record is accurate and terrified of having to retract a publication. This transfers to our research groups – the punishment for falsifying data in my group is immediate dismissal from the lab and reporting to the Dean of Students and Graduate School.

#2 – This is where peer review shines. We evaulate whether 1) the appropriate data are present to draw the conclusions and 2) whether the presented data actually support the conclusion in question.

I’m very interested in your response to #3 and the problem statement you provide. Could you give an example of what you mean by something “actually studied” vs “something less rigorously…studied” (i.e. what would fall in each bucket)? Also, are you thinking mostly that experimental design is driven by bias or conflict of interest? Or that topic selection – i.e. the questions scientist think to ask – are influenced by bias, conscious or unconscious?

Brian

I believe you are getting into the big 6 from “Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion” (R. Cialdini) here, specifically a problem with two of them: commitment/consistency and authority.

From the book: “The drive to be (and look) consistent constitutes a highly potent weapon of social influence, often causing us to act in ways that are clearly contrary to our own best interests” (pg59). Humans in general trust people less who aren’t consistent. This also drives the againsts. Once someone’s come out publicly and said the pandemic isn’t real or are against vaccines (or vice versa) it’s hard for people to reverse direction.

I think the world is full of examples of experts being severely chastised for changing direction so in time have learned to just change direction and ignore the rest.

SC

Is this a product of the tribal homogeneity of the experts? Or that experts have politicized themselves by engaging in the fray rather than sticking to the scholarly aspects?

Based on direct observations I say that most scientists wrongly believe that their thought processes occur without bias, and I think that’s because they don’t understand how/why the formation of bias is inevitable. Bias cannot be denied, it should be managed in a way that minimizes its impact on conclusions and decisions, but scientists insist on denying that bias could exist among them. Many seem to believe that admitting to bias in their thinking would constitute “failure” in a professional sense and denying the existence of bias is for them a matter of defending their professional integrity. Bias inevitable shapes research projects, methods of sample selection, methods of analysis, arrival at conclusions, making inferences based on conclusions and presenting them as known facts, and employing clever communication techniques to publish and promote all of this. They seem to truly have no conscious understanding that bias is inevitable and that they are at least just as prone to it as all other humans and possibly more prone to it if their personal ego is built around the identity of “expert”. If the issue of bias is meaningfully addressed there should be no reason why academics should “stick to the scholarly aspects”, and if that were to happen, their involvement in those aspects would be more contributory and less dictatorial. They would provide valuable input and would once again be respected for that value, as they would presumably also respect and value the input and consideration of other stakeholders with whatever non-scholarly domain the “aspect” exists.