Looking for Laffer-Likes

To learn more about Epsilon Theory and be notified when we release new content sign up here. You’ll receive an email every week and your information will never be shared with anyone else.

Continue the discussion at the Epsilon Theory Forum

The Latest From Epsilon Theory

This commentary is being provided to you as general information only and should not be taken as investment advice. The opinions expressed in these materials represent the personal views of the author(s). It is not investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. Any action that you take as a result of information contained in this document is ultimately your responsibility. Epsilon Theory will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information. Consult your investment advisor before making any investment decisions. It must be noted, that no one can accurately predict the future of the market with certainty or guarantee future investment performance. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

Statements in this communication are forward-looking statements. The forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date of this publication. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Epsilon Theory disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein. This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. This commentary has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. Epsilon Theory recommends that investors independently evaluate particular investments and strategies, and encourages investors to seek the advice of a financial advisor. The appropriateness of a particular investment or strategy will depend on an investor’s individual circumstances and objectives.

Great perspective, we get caught up in the minutia too much sometime…made me think of another recent good read!

Of Dollars and Data Blog…

"In Everybody Lies, Seth Stephens-Davidowitz illustrates how the news media doesn’t influence peoples’ beliefs, but rather, the audience determines what kinds of stories news agencies cover and publish. He states:

Many people, particularly Marxists, have viewed American journalism as controlled by rich people or corporations with the goal of influencing the masses, perhaps to push people toward their political views. Gentzkow and Shapiro’s paper suggests, however, that this is not the predominant motivation owners. The owners of the American press, instead, are primarily giving the masses what they want so that the owners can become even richer…There is no grand conspiracy. There is just capitalism.

Stephens-Davidowitz’s conclusion suggests that you are the gatekeeper to your own mind. You decide what comes in. You decide what sticks. So whether you see the universe as kind or hostile, this belief will flow through your entire belief system and affect all the others. When you choose between kindness and hostility, choose wisely."

Situational Awareness! Reset, look again, look at what’s not said, move upstream, get to high ground! Get a different look! High Risk Decisions for Low Risk Outcomes or vice versa…

Yes, I agree that at times it can be difficult to differentiate between giving people “what they want” and exploiting the vulnerability we have to narratives that seem convenient to our own perspective!

This is kind of a reverse reductio-ad-absurdum argument where the premise is true at the extremes, but is not a continuum in the middle. That said, IMHO, it probably is a continuum, i.e., tax rates and revenues are inversely related, although with varying first derivative rates along its continuum. However, in a real economy, the impact of small changes to tax rates on government revenue can easily be overwhelmed by all the other variables at play.

An example that fits Rusty’s point even better might be government debt and interest rates - away from the extremes, there appears to be no consistent correlation. And Japan is, at minimum, proving that the extreme of one end of the relationship is farther out than previously believed.

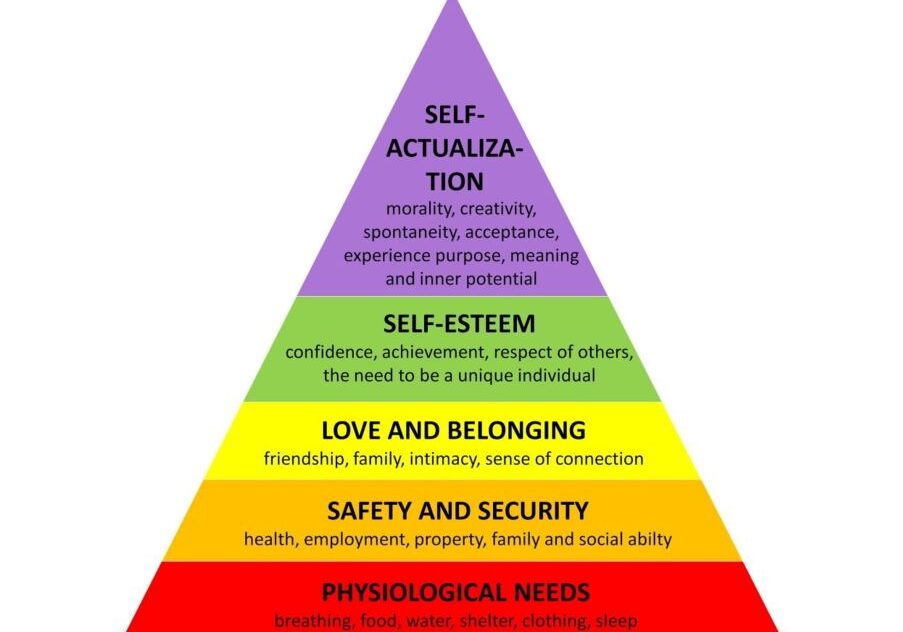

My take is that it is the simplicity of the two-variables model that is core to the flaw in “laffer-like” beliefs. Rarely in any system are two and only two variables the factors which determine outcomes. We live in a complex inter-related world and do ourselves a disservice believing we can distill the complexities into a 2-dimensional model. This flaw is repeated in every aspect of our lives. Here are two examples outside of Politics and markets: physical fitness: how much you workout vs what you eat = weight gain/loss or school: how much you study vs raw intellect = academic success. each of these are equally flawed as the laffer-likes…