It is all very well and good for someone like me to write about work.

I have never really wanted for anything. My father had a good job. He spent his entire career as an engineer with the Dow Chemical Company. My mother was a homemaker. We were square in the squarest middle of the American middle class. Me personally? I was even more fortunate. I was a kid with good test scores from a poor, rural high school that no one had heard of, so I got to hop in the short line to get the Team Elite stamp on my passport. I’m a terrible person to lecture you about how you should think about your relationship to your work.

Hear me anyway: Your work is holy.

very inspiring, Rusty.

“there is no substitute for spending time in what others consider to be an elite segment of your profession, preferably at an elite institution, and probably in a big city”

Oh, easy! They let anyone work there, right? Should I tell them in advance that I’m coming or should I just assume they are expecting me? : )

Just pretend to have an appointment! But all kidding aside, it’s a stupid and unfortunate reality.

Thanks, DR!

One of my greatest joys as a supervisor is connecting the employees and volunteers I supervise with the value and meaning of their work. Oftentimes they don’t have the perspective to see how the small actual work products they produce fit within the big picture. Often what seems of little significance is in fact very significant. One of the things I’ve noticed with millennials in particular is they want to jump straight to doing the big thing, often not recognizing the value and importance of the the little things.

A further point on the abstraction of work: The ability to tell if one has done “good work” based on an objective result. Like a carpenter seeing whether the door jamb is plumb or not. Or a surgeon seeing if his patient got better or not. These are objective measures of success.

The abstracted work of the knowledge economy is judged by the fickle opinion of others. The 360 job review. The page views. The retweets.

“Other people’s heads are too wretched a place for true happiness to have its seat.” ― Arthur Schopenhauer,

This phenomenon was well described in Shop Class as Soulcraft: An Inquiry into the Value of Work by Matthew Crawford.

I am not sure if it’s OK to post links, but this is the book:

https://www.amazon.com/Shop-Class-Soulcraft-Inquiry-Value/dp/0143117467

Bravo! It seems that ‘workism’ is a narrative abstraction of one’s own work - where one’s task is not to accomplish some worthy goal, but to try to become their own mini-missionary in an attempt to weave and control their own office narrative, totally abstracted from the real work, to convince those above you to check the right boxes and move you up.

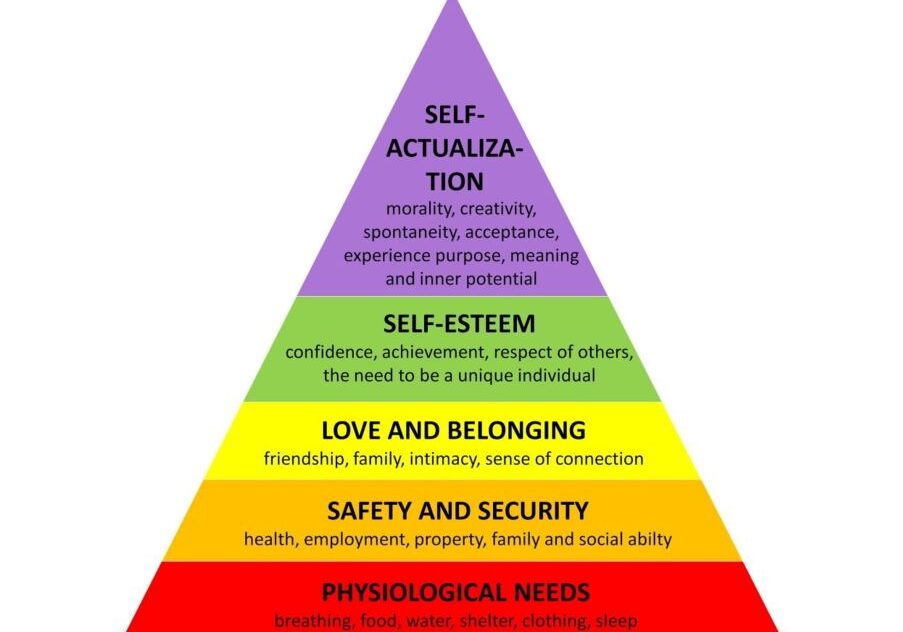

This piece immediately brought to mind Victor Frankl: “What man actually needs is not a tensionless state but rather the striving and struggling for a worthwhile goal, a freely chosen task,”

“the self-tracendence of human experience denotes the fact that being human always points, and is directed, to something or someone, other than oneself - be it a meaning to fulfill or another human being to encounter. The more one forgets himself - by giving himself to a cause to serve or another person to love - the more human he is and the more he actualizes himself,”

Excellent post. Every white collar professional should probably read this, but especially those still at the early stages of careers. No pdf version of this available?

It started as a brief and got longer! We’ll get a PDF together (will probably send by email on Tues and post to website over the weekend).

Totally fine to post links. And yes, I think that the subjectivity of feedback to workism-sensitive roles is a very good point. I hadn’t really considered it.