In this conclusion to the Things Fall Apart series, I’m going to share with you what I’m doing with with MY political participation and MY market participation. You can decide if my application of the Clear Eyes, Full Hearts process makes sense for you, and in what ways. It’s a lot to describe, so I’m going to divide it up into two notes. This note will be about what-to-do in investing, and my next note will be about what-to-do in politics.

Okay … what-to-do in investing.

To set the stage for this I’m going to use a comic book quote. I know, I know … quelle surprise.

In the Sandman comics by Neil Gaiman, Dream of the Endless must play the Oldest Game with a demon Archduke of Hell to recover some items that were stolen from him. What is the Oldest Game? It’s a battle of wits and words. You see it all the time in mythology as a challenge of riddles; Gaiman depicts it as a battle of verbal imagery and metaphors.

Here’s the money quote from Gaiman:

"There are many ways to lose the Oldest Game. Failure of nerve, hesitation, being unable to shift into a defensive shape. Lack of imagination."

“A risk is something where we can assign some sort of reasonable probability to its occurrence…”

Three of the Horsemen are “risks”. Two of them, maybe all three, are non-recurring. How do you assign a probability to a non-repeatable event, or do you mean guesstimate as a process? You can assign probabilities to guesstimators. Do you use a coterie, either public or private, to assign the ‘reasonable probability’?

(I realize this is not about your main point.)

You just keep upping your game, Ben! When you say “there’s an argument for Bitcoin here” aren’t you really talking about Blockchain Technology broadly? Doesn’t this reaffirm what Neville Crawley wrote about on September 24 in his guest post re an Alternative Data Infrastructure System?

I filled out an online form today and one of the fields was country of residence. I had to scroll a lot to get to United States, and I realized that it’s usually at the top. I had a kind of frisson that this was what it was like living in a country that didn’t have the world’s reserve currency. I don’t know if it’s gold, SDRs, Bitcoin, or moonbeams, but if the world picks another reserve currency, American life changes fast.

I was asked once what really backs the US Dollar, and I said, “12 aircraft carriers.” You want an out of the blue, unimagined, unknown-unknown? Someone even gets close to putting a dent in one of those ships, and common knowledge that America rules the sea lanes will change quickly.

I agree, I always thought that Wall Street and economists underestimate (ignore? / don’t even think about?) the military component supporting the world’s reserve currency.

Since the last world war ended in '45 and the Cold one in ~'90 (and the Soviet economy and political structure was never going to support a reserve currency anyway), the military-might aspect has gone from being taken for granted to being almost forgotten about. It’s no coincidence that the British pound gave way to the US dollar as the reserve currency at the same time that the military fortunes of the two countries were moving in opposite directions.

Ben - thoughts on Gold? If, as you’ve noted, it’s insurance against CB failure, I have to assume you see it as part of the strategy when the Fourth Horseman arrives (carrying the 1970s economy in his saddle bag) and undermines CB credibility?

YES. And this will be at the heart of my what-to-do in politics note, the companion piece to this one.

It’s not my main point, but it’s an important question! You’re absolutely right that you can’t just “assign a probability” to, say, an Italy-driven Euro crisis, and this is exactly why it is a (very) poorly-specified risk. What you CAN do, however, is create a path set or event tree where some of the paths and tree branches ultimately end in a Euro crisis, and evaluate the nodes (sub-events) that take you along one of those paths or branches. The closer the node, the better you can estimate a probability, even if the far off nodes are not effectively estimatable AT ALL. This is exactly why I think it’s necessary to REACT to these poorly defined event risks if and only if they actually occur, as opposed to hedging in advance. If you hedge in advance, you’re really just hedging one of the sub-nodes, and you almost never get a fair price on that.

There are a couple of thoughtful guys out there who have been ringing a bell about this possibility. My sense is that it’s like a runaway federal budget deficit. Is it a serious and real unknown unknown that would change our fundamental investment fabric? ABSOLUTELY! Is there any sort of narrative being created that would change common knowledge (and thus behaviors) on this? No. And unless and until I see that narrative, I think we’ve got time before we have to DO anything to protect our portfolios from this uncertainty. That’s not to diminish its importance, but to explain how I think about its demands on my portfolio decisions TODAY.

Yes, I think the meaning of gold today is as an insurance policy against CB failure. And I think it’s a pretty cheap insurance policy! That said (and this definitely deserves its own note) I just can’t shake this nagging doubt that it will be as effective an insurance policy as it has been in the past. To be continued …

“God help us, but there’s an argument for Bitcoin here.”

Looking forward to more in-depth discussions on this!

We actually just published a 100-page long thesis on what’s really driving the cryptocurrency phenomenon (https://iterative.capital/thesis/). This traces back to the origin & cultural context of open-source software, cypherpunk movement, and how Bitcoin coordinates around human & machine consensus. We spent a lot of time on this. Promise this is not marketing/shill. I genuinely want to hear feedbacks from Epsilon Pack.

Interesting allegory of the four horsemen, especially where China and Inflation fall in order (War & Death).

Does it change the outlook if the three horseman arrive together or just lengthen the recovery timeline. At present all 3 narratives seem to be in play.I

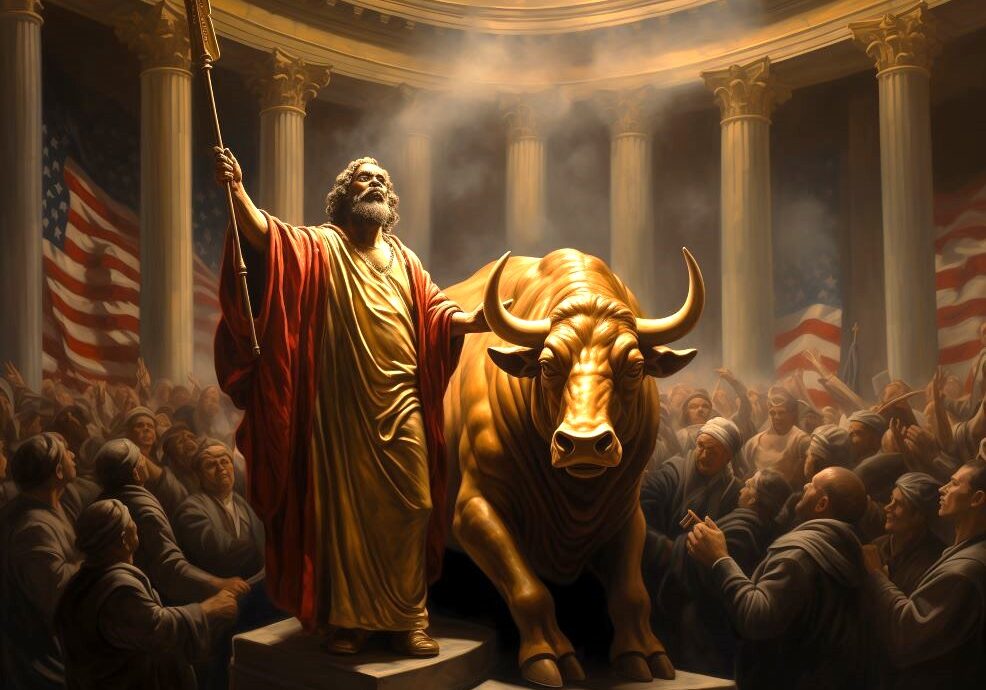

Biblically speaking the four horsemen arrive together, with Hell following. Can we imagine a scenario where markets and participants encounter your four horsemen at the same time? Would certainly seem like Hell for asset managers.