Let Us Now Praise Famous Men

To learn more about Epsilon Theory and be notified when we release new content sign up here. You’ll receive an email every week and your information will never be shared with anyone else.

Continue the discussion at the Epsilon Theory Forum

The Latest From Epsilon Theory

This commentary is being provided to you as general information only and should not be taken as investment advice. The opinions expressed in these materials represent the personal views of the author(s). It is not investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. Any action that you take as a result of information contained in this document is ultimately your responsibility. Epsilon Theory will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information. Consult your investment advisor before making any investment decisions. It must be noted, that no one can accurately predict the future of the market with certainty or guarantee future investment performance. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

Statements in this communication are forward-looking statements. The forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date of this publication. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Epsilon Theory disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein. This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. This commentary has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. Epsilon Theory recommends that investors independently evaluate particular investments and strategies, and encourages investors to seek the advice of a financial advisor. The appropriateness of a particular investment or strategy will depend on an investor’s individual circumstances and objectives.

So much good stuff here…learning by the day!

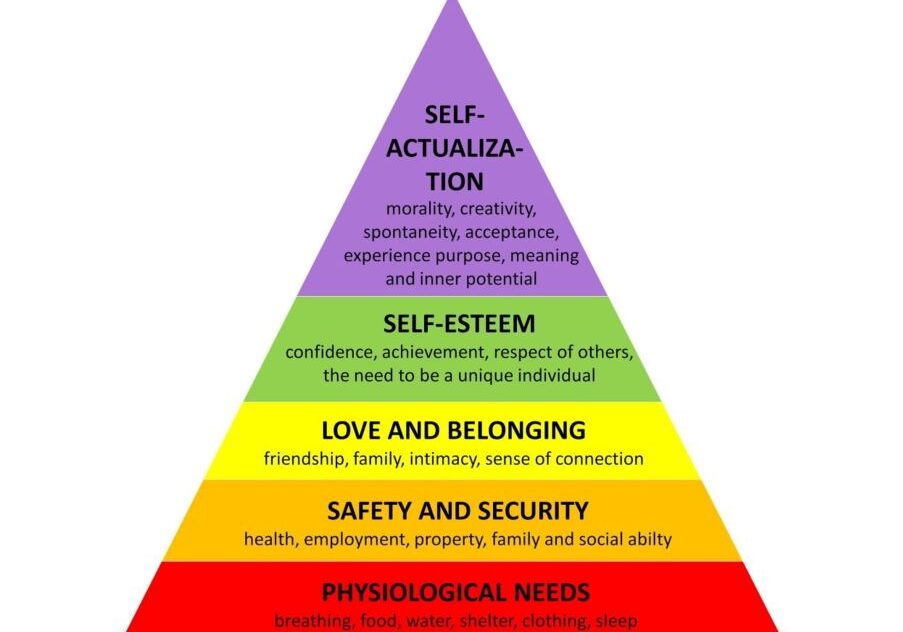

Rambling thoughts: Inflation is a tax…taking on more risk is a tax…bullshit is a tax. What these management teams do or don’t do is simply a process of being conditioned by their environment. Nature does not care about your morality or lack there/of. Quant’s talk a lot about process…I equate process with zero tolerance…I have zero tolerance for zero tolerance. You better know when/how to break your process and evolve before time elapses on you and your Team. When a Team is on the “X”, the longer they stay on the “X” the higher their risk increases toward a negative condition which can/will turn quickly into a crisis. Adapt or Die!

The ET piece that finally made me see this note’s point clearly was, oddly, not one of the ones Ben mentions here, but one from July 2015 titled “Catch - 22.” Since, I can’t paraphrase it half as well as Ben wrote it, I’ll just quote (which sounds so much more sophisticated than “copy and paste”) it here:

“Here’s the Fed’s Catch-22. If the Fed can use extraordinary monetary policy measures to force market risk-taking (the avowed intention of both Zero Interest Rate Policy and Large Scale Asset Purchases) AND the real economy engages in productive risk-taking (small business loan demand, wage increases, business investment for growth, etc.), THEN we have a self-sustaining and robust economic recovery underway. But the Fed’s extraordinary efforts to force market risk-taking and inflate financial assets discourage productive risk-taking in the real economy, both because the Fed’s easy money is used by corporations for non-productive uses (stock buy-backs, anyone?) and because no one is willing to invest ahead of global growth when no one believes that the leading indicator of that growth – the stock market – means what it used to mean.”

It was like a light went on in my head (true, the brightest bulb up there is 60 watts, but it went on anyway) when I read that line. Now I will need some time to think about this line as I “get it,” but don’t “own it” yet:

“Sorry, Mr. Friedman, but inflation is not a monetary phenomenon in anything but a tautological sense. Inflation is always and everywhere a risk-taking phenomenon.”

Nice to see ET firing out of the gate in 2019 as strongly as it was running in 2018. Thank you Ben and Rusty for, not just writing thought-provoking pieces (which you guys do with incredibly frequency), but for building and sharing a new perspective and approach to trading, investing, markets and humans, in general. Because of you guys, I’m becoming better in all four of those areas.

Could it be that companies have not innovated, because they have outsourced that to the Technology/Start Up world? At least in the technology world (which is really all I know), the giants (FAAMG and Oracle, Cisco, CA etc.) have watched the startup landscape and acquired companies that look promising and done pretty well at it.

There are several large company that tried monitoring and acquiring innovation and have only succeed in imploding (IBM, GE, Verizon etc.)

Also, there are smaller companies that acquired startups that have done amazingly well (NY Times with Wirecutter, Conde Nast with Reddit)

Additionally, there are startups that don’t challenge FAAMG and have grown on their own.

But this is all in the technology space, where there has been a good amount of innovation and the pace seems to only be picking up.

Wow! That’s quite a narrative: an efflorescence of c-suite sagacity transmutes the bitter medicine of monetary miserliness into an intoxicating elixir of productivity plus rising wages and prices. If originality and audacity are the keys to winning the day, this story is hard to beat. But there’s another narrative from another Hunt (Lacy, not Ben) that’s all about the data. Here’s an excerpt from what this Dr. Hunt wrote back in October: “Recently, San Francisco Fed economists conducted a study on various spreads in the treasury market. Using monthly data from January 1972 through July 2018, they looked at each spread and predicted whether the economy would be in recession 12 months in the future. The study found that the ten year-three month (10y3m) spread was the “most reliable predictor” in signaling a recession. . . . if this yield spread is still positive but falls below +40 bps, there is a more than reasonable possibility of a decline in economic activity.” (full text here: http://www.hoisingtonmgt.com/pdf/HIM2018Q3NP.pdf) As I write this, the spread languishes at 20 bps.

So there you have it: Hunt vs. Hunt. You pays yer money, and you takes yer choice.

Ben, your stuff is confusing. Here is how I understand it. CB’s goal is here to help capital, print money at bad times to prevent bad business from goin under and this creates many Zombie businesses which hires a lot of labor and labor becomes expensive and start to hurt capital. Then CB will tighten to kill the Zombies and get some folks to lose their jobs so that capital have more negotiation power over labor, kill wage inflation. Okay, now, you are saying the past 10 years have been Golden Age for managements who are so smart to use minmax regret strategies and the are so robust now that even when valuations takes it on the chin, these companies will NOT die, and rising rate will force them to take real world investment risks and inflation will NOT be contained. So money printing has created Zombies that are soooooo minmax-regret that they will NOT die? Even when FED is trying to help capital kill labors by raising rates, the capital have to use more labor to take risk and cause wage inflation?

What’s also puzzling is that Elon Musk, AKA a raccoon, is NOT one of those share buy back minmax-regret CEO. He is one of those real world risk taking while everybody else is minmax-regret processing. Some how you use his name as an example of the golden age minmax-regret CEO. I thought Tesla is more like a Zombie company run by a raccoon and FED should kill it to release the labor for other golden age management companies.

Having been in various finance positions in corporations the last 12 years - some other things are key - not going public (if not already) - just cheaper and easier to operate; hiring less young, inexperienced people and wasting efforts and money on training task-rabbits vs. investing in technology or 3rd party services or hiring more experienced older operators who can change things quickly and easily harmonize to the industry best practices. For public companies and even some private make sure any large outlays are part of non-recurring items like M&A, restructuring, efficiency programs, divestment, etc. - so maximizing shifting funds to places that can be removed in the Adjusted EBITDA calculation. Lastly, I believe it is just drastically cheaper to maximize the share price rather then grow revenue - and share repurchases or debt service do not show up in Operating Income and EBITDA anyway so even if they don’t work, it’s not that visible.

Yet another diatribe from Ben arguing to sell vol.