Derivative Hoops

To learn more about Epsilon Theory and be notified when we release new content sign up here. You’ll receive an email every week and your information will never be shared with anyone else.

Continue the discussion at the Epsilon Theory Forum

The Latest From Epsilon Theory

This commentary is being provided to you as general information only and should not be taken as investment advice. The opinions expressed in these materials represent the personal views of the author(s). It is not investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. Any action that you take as a result of information contained in this document is ultimately your responsibility. Epsilon Theory will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information. Consult your investment advisor before making any investment decisions. It must be noted, that no one can accurately predict the future of the market with certainty or guarantee future investment performance. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

Statements in this communication are forward-looking statements. The forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date of this publication. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Epsilon Theory disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein. This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. This commentary has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. Epsilon Theory recommends that investors independently evaluate particular investments and strategies, and encourages investors to seek the advice of a financial advisor. The appropriateness of a particular investment or strategy will depend on an investor’s individual circumstances and objectives.

This is remarkably spot-on as a take. Personally, while I was a huge NY Knicks fan growing up in the NY suburbs, the game evolved over time from the quintessential team sport, where all 5 players contributed constantly, to a superstar focused playground sport with teams seeking the biggest star and clearing half the court to let him do his thing and bring the team to victory. Alas, that was a far less interesting game, especially for the core audience of kids who played basketball in rec leagues or school or even on friends’ driveways, and who learned much about teamwork and its importance in that setting. Add to that the willingness to celebrate players of morally dubious character (Latrell Sprewell anyone?) simply added to the growing disenchantment. At this point, I no longer watch nor care about the Knicks or the NBA.

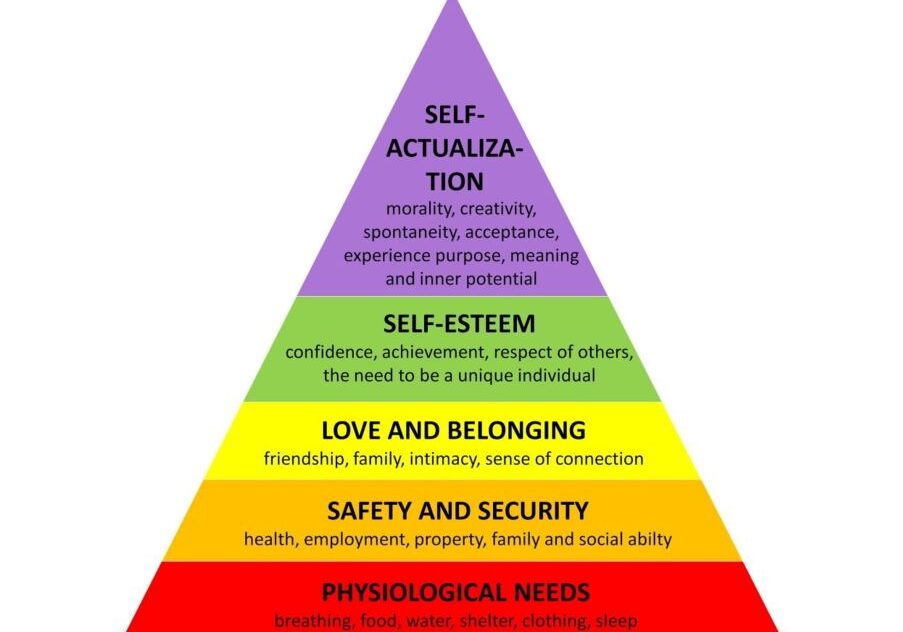

And the analogy to our economy and the real world is extremely accurate and telling. How many things that seemed important to us all earlier in life have become almost parodies of themselves and now carry no weight or import at all?

thank you for a thoughtful discussion here.

Terrific! Eventually, please do other sports, like PGA / LIV. And are the players actually paid the astronomical sums quoted in the press (e.g. Cristiano Ronaldo > 130m annual, > 1b lifetime), or is it a marketing ploy?

This was a fantastic post! Watching owners create synthetics to juice returns for their investments in these teams where the prior 30 years cannot be replicated rings very similar to the United States of BBY article. But BBY was a dying retailer made less relevant by AMZN. Pro sports are tied to the cultural fabric of modern society and I hate to say it but that society will be willing to tolerate the synthetics for much longer than anyone commenting on this kind of article would like.

As a follow up article at some point Hubbie I’d be interested to see a post about the NFL’s Thursday night football. The quality of play is horrible, player safety willfully ignored but hey the NFL can squeeze some more money out of another TV network so the show goes on!

Really interesting read, even if one is not necessarily an NBA fan. The concept “thermocline” was a new one for me, and I am chewing on that tasty bite of knowledge!

I had read recently that the “San Francisco” 49ers are slowly taking over the town of Santa Clara, whose voters decided to help fund the stadium that San Franciscans were reluctant to. Proving your point, sadly. 49ers faction in Santa Clara wants to topple elected police chief

And from a business model innovation perspective I’m thinking about “too many games” and wonder how fans/customers of the games might be more or better engaged around the game of basketball itself. I don’t know if it maps to basketball but e.g. I’m thinking about how Lego lets its fan base create products that sometimes get taken up by the company to produce as a series.