Marc Rubinstein has over 25 years experience as an analyst and investor in the financials sector which he distills into a weekly newsletter, Net Interest, which I think is a really great read! Between 2006 and 2016 he was senior analyst and portfolio manager on the Lansdowne Global Financials Fund, a fundamental long/short equity fund focused exclusively on the global financials sector. Prior to that, Marc was an Institutional Investor ranked analyst on the sell-side, most recently at Credit Suisse, where he was a managing director overseeing its European banks team. As well as writing Net Interest, Marc is an active angel investor in fintech. He can be contacted via his newsletter or on Twitter (@MarcRuby).

As with all of our guest contributors, Marc’s post may not represent the views of Epsilon Theory or Second Foundation Partners, and should not be construed as advice to purchase or sell any security.

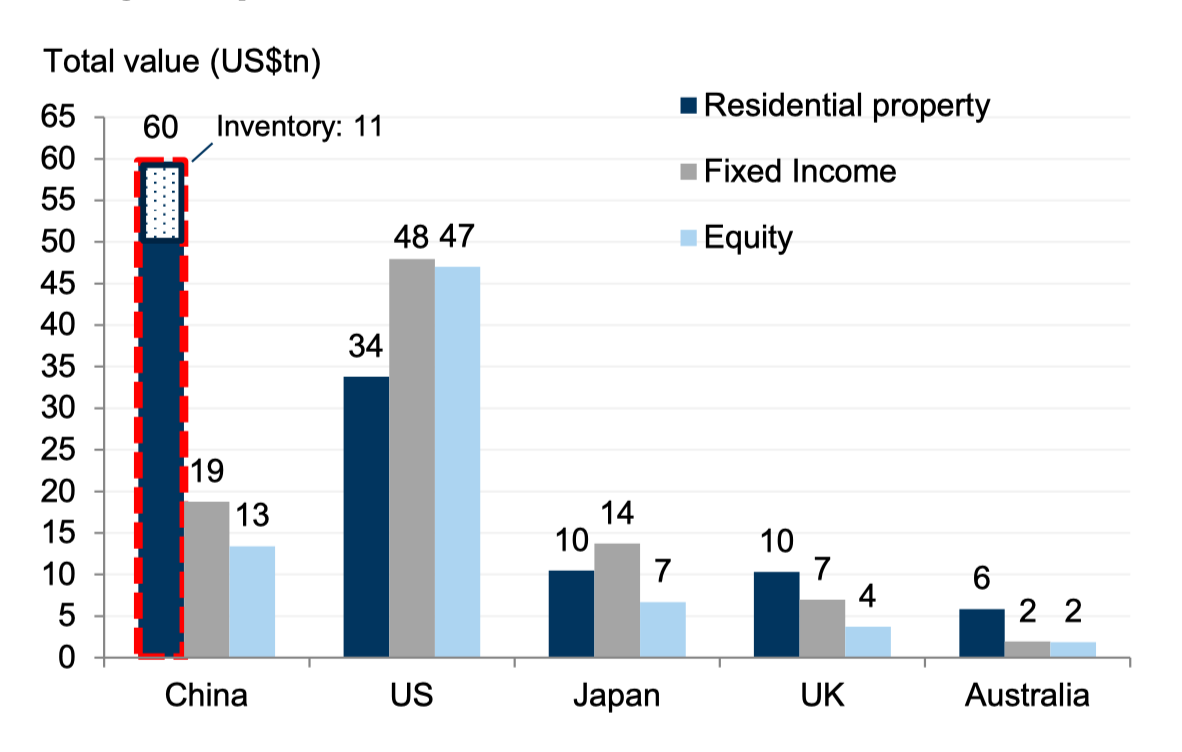

It’s been described as “the most important sector in the universe” and it’s easy to see why. The Chinese property sector is first and foremost big. The total value of all the homes in China stands at $60 trillion – twice the size of the US residential market and bigger even than the entire US bond market. The Chinese property market is probably the largest asset class globally.

It’s also central to the economy. Real estate investment stood at over 13% of GDP in 2019, of which more than 70% was linked to residential building. Add in the contribution of the construction industry and the share jumps closer to 29%. Yet even this potentially understates the importance of property to the economy: Housing accounts for almost two-thirds of households’ overall assets – compared with around a third in Japan and a quarter in the US – so it has a major bearing on people’s spending decisions. [1]

It’s central to government finances, too. Since changing its constitution to allow land-use rights to be bought and sold under long term leases, the Chinese state has relied on land sales to raise funds to meet its budget. Based on data from the IMF, revenues from land sales accounted for around 39% of local government revenues, equivalent to 7% of GDP, in 2017.

And it’s central to the financial system. Banks rely on real estate and land holdings as the main source of collateral to secure loans. Housing loans account for around a third of banks’ loan books and have grown more quickly than other loan categories.

Astounding that this note got no comments from the Pack! Why?

I theorize that none of us know what to make of this situation to confidently comment about how it fits in the global financial landscape… It has been festering for over a year, has resulted in trading halts in the equities of affected developers, and yet hasn’t suppressed the urge to speculate on Chinese listed stocks. It is important but doesn’t exactly fit a narrative that would take hold in developed markets.

As such, I think it is a metaphor for hidden risks in the narratives we are seeing about the Fed, inflation, the business cycle, and financial market stability. This very large and hard to solve problem exists but seems to exert nearly no influence on market sentiment. Seeing that makes it easier to theorize that investors are also not thinking too critically about how serious the energy situation in Europe will be this winter, or how long it will actually take to see inflation land back in the zone that is being forecast.

I saw this tweet from Jim Bianco last week and it speaks volumes about the complacency around the outlook for inflation and how quickly it will fade.

That chart is a goodie. Financial guru’s everywhere are convinced in the god-like powers of the Fed. Inflation slowdown is right around the corner… what if it’s not? Europe energy is fucked, China real estate is fucked (will need a lot of QE handouts to banks to fix).

Looks to me that inflation has a high chance of becoming entrenched in the markets. I don’t believe the Fed can raise rates high enough to combat inflation without bankrupting the country (USA has a massive debt load). What happens when inflation doesn’t come down and the traditional tools like rate-raising isn’t available?

I don’t think our fiat and debt based financial system is sustainable and there may be a reckoning sooner than later. Bitcoin anyone?

The long anticipated, and completely expected, ascension of Xi to a life term happened over the weekend. Complete with the awkward removal of any rivals who were said to be feeling under the weather as they were escorted out. And, Wall Street seems to be SHOCKED (based on the price action in the currency and popular stocks). The Chinese property leverage crisis isn’t fixed, the rule of law drifts further from shore; yet I saw raccoon after raccoon advocating for an overweight of Chinese equities in the past few months for various reasons. These additional developments don’t lessen the set of risks in the Hong Kong financial markets and the biggest Chinese stocks remain important weightings in global indexes.

Deafening silence from the China profiteers. Good luck to the Western lenders to Evergrande and its many peers looking for their recovery in bankruptcy court.

If you’ve ever heard a swan in flight, the sound is unmistakable. The whistling of the wings, and the rhythmic beat of those huge wings moving through air. To me the Evergrande and Chinese property crisis is a lot like that. It’s like being in the marsh before dawn in the silence. I hear the unmistakable sound of the black swan’s wings flying overhead. I don’t know where it’s going to land, and I can’t shoot at what is only a sound in the darkness.

That metaphor resonates! I just heard Bloomberg’s Damian Sassower, their Emerging Markets credit analyst, he threw out $6.3 trillion as the size of Chinese property debt that is teetering. Other hard to believe stats in the interview were that 94% of dollar denominated Chinese property debt trades for under 70 cents on the dollar; and, local government financed vehicles are now defaulting. Nearly $300 billion in US $ property debt bonds must be refinanced by the end of 2023. This asset underpins the Chinese banking sector, household wealth and their economy.

This is the largest credit market on the planet according to the Rubinstein article that started this thread! How are investors obsessing over every possible Fed narrative of pause or no pause when this house of cards is fluttering in the breeze of those swan wings?

When thinking about a world where negative interest rates are being withdrawn and deleveraging looms, investors need help gaming through what happens to this asset class and all of its constituents. I only know enough to realize it is important and ignored.

I think the market is so sanguine about it because everyone knows that everyone knows there is no way the CCP are letting the Chinese property market implode ala US 2009 crash. And considering that they have WAY more control and ability to literally force individuals, sectors and investors into doing what they want in many cases, it is not inconceivable that the CCP figures out a way to hide the losses and paper them over in a way that prevents a systemic crash. Because the narrative assumption is that the CCP can’t let the property market crash because it’ll piss too many people off and potentially foment dissent, disorder and anger amongst the masses, which common knowledge is that the CCP do not want this.

But if you want to go to war, especially with someone who has a larger army and will inflict massive casualties (ala the US) then you need your populace mad, angry and disappointed with their prospects outside of the military. Especially if you can spin it so that the pain and suffering they’re experiencing is due to said enemy,

As always with China, knowing the priorities of the CCP is key and unfortunately, the market has a hard time remembering that past performance is not reflective of future returns, especially when it comes to China. If the CCP change their priorities (doesn’t necessarily need to be war oriented, a lack of concern of future foreign investors and dollar denominated debt issuance could also fit this reorientation of priorities) but the market assumes business as usual, a lot of people are in for some pain.

I don’t have strong views on this as I am in no way an expert on China. I agree the narrative is that the CCP won’t let this important domino fall without exerting emergency measures as it would topple their financial system. But, it is so large and has investors from outside their closed system. However it is handled, the currency will almost certainly face pressure to be further devalued. I also see others who have had success looking around dark corners into opaque structures betting their reputation and their fortunes on the Chinese banking system coming under serious stress (Kyle Bass).

The other aspect which gets deeper into credit derivatives than my surface level understanding, is how credit tremors that start in China will ripple through other collateral chains. Are Japanese, European, and US private real estate and credit investors hung out on this asset class? There were early rumblings at the start of the crypto winter that some of the Tether commercial paper was invested in Evergrande bonds. Will Hong Kong be subsumed more directly by the CCP for the real estate asset base it would give to the Chinese to offset some of the trillions in loss?

When the credit tide goes out, it pulls on many securities that are only peripherally related. The subprime credit crisis of the GFC was so damaging due to the leverage that was unseen until access to borrowing vanished.

Maybe I missed it in the many threads, but I have not seen much coverage at all in mainstream nor here on the Country Gardens situation. Their 8% bonds due in 2024 are trading at 8 cents on the dollar. First half of 22 they claimed earnings of 210 million…they are expecting a loss of 5 billion this quarter. Gavekal research is pegging the China RE issue at $390 billion.

I am not as smart as most on here so maybe I am missing why this is not front page of pretty much everything not involving war. I feel like I am in the movie Don’t Look Up.

I agree! For some reason the implosion is barely part of the narrative while it is both more critical within country due to size and scope AND shows the utter lack of fiscal response since first domino Evergrande fell in 2022. The CCP continues in defiance of Western missionaries clamoring for massive stimulus. The only place it seems to be causing ripples is via a weakening Yuan. And, I did post an update to the other China thread on the Forum about a week ago… that also got no replies!!

You and I must be missing something. I am reading an article today that is referring to it as China’s Lehman moment (has now leaked over into Zhongrong trust company) and yet it is a very secondary article. The mainstream I expect a lot of times to miss things, but I think of Epsilon as a bit more preceptive on things like this and it seems like everyone is ignoring it. There must be some reason this isn’t big deal that I just don’t get.

https://www.msn.com/en-us/money/realestate/china-s-real-estate-crisis-echoes-lehman-moment-country-garden-warns-of-major-uncertainties-as-bond-redemption-looms/ar-AA1flNRm?ocid=socialshare&cvid=eca373847fe54b49ab8523aba4c56074&ei=7