There Can Be Only Two

January 27, 2026·5 comments

Grant Williams is not only the nicest guy and best interviewer in finance, he's also one of the keenest observers of the global economic picture. In addition to his myriad of podcasts (over 1 million downloads!), Grant relates his insights in a monthly newsletter called Things That Make You Go Hmmm..., which I can't recommend highly enough. I'm thrilled to report that Grant has not only allowed us to republish last month's tour de force note outside of both his paywall and our paywall, but he will also be joining me on Friday, January 30th from 2-3 pm for Office Hours, our weekly live conversation with Epsilon Theory subscribers. And yes, we will be recording this for subscriber replay!

There is a natural human inclination, when contemplating the possibility that the dollar might one day lose its pre-eminent position at the centre of the global financial system, to assume that it must happen with a certain dramatic inevitability.

We expect currency transitions to behave like revolutions, to arrive clothed in crisis, rupture and present themselves clearly as a moment when one world ends and another begins. Instinctively, we look for a collapse large enough to feel definitive, something that will one day be referenced as the turning point. However, even a cursory glance back through monetary history will demonstrate that history has always been, and remains, entirely unmoved by our narrative preferences.

This kind of change takes shape quietly, often unnoticed, until structures that once seemed permanent are proven to have thinned beyond repair. None of the great monetary transitions of the past have arrived with banners flying, treaties signed or central bankers declaring a new age. Instead, they’ve unfolded through redirection rather than revolution, and through decisions made at the margins long before any public recognition followed. Behaviour changes first, narratives later, and by the time a new story becomes widely accepted, the system beneath it has already moved on. This is what makes the contemporary debate surrounding what’s become known as de-dollarisation both so important and so misframed. It’s commonly discussed as though it were a new arena of geopolitical confrontation, an emerging currency war in which China and the United States are destined to contest supremacy in some grand and visible struggle, with an eventual and obvious winner emerging. That framing feels intuitive to us because it borrows from familiar historical language.

The Thucydides Trap, The Great Power Competition— however you want to frame it, the structure of the story is the same: great powers rise, great powers fall and a tense rivalry produces disruption and potential replacement.

However, the closer one looks at monetary history, the more inadequate this lens becomes. Reserve currencies are not dethroned in public and they don’t fall because someone else declares ambition with sufficient confidence or volume. They lose their position when the world either discovers that it no longer needs them quite as much as it once did, or when the incumbent either overplays its hand, or stretches itself to the point where it no longer offers a viable path to repayment of the debts that build up in such a system.

At that point, we tend to wake up and find that something else, perhaps imperfect but useful enough, has quietly taken its place.

Take, for example, the rise of the US dollar.

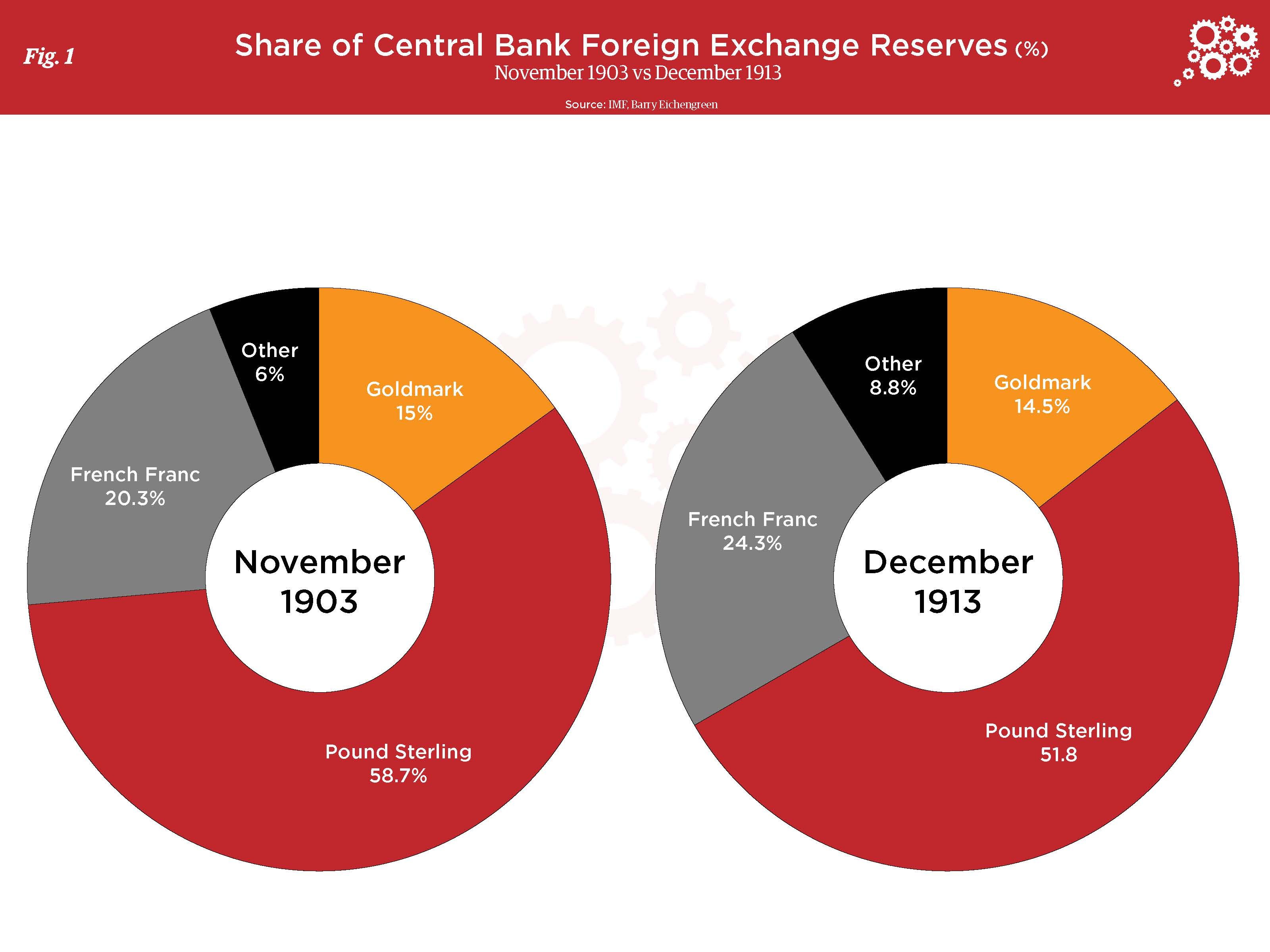

If we go back to the 19th century, when Great Britain was, well, Great, the composition of Central Bank currency reserves reflected the tiny island nation’s supremacy with almost 60% of Central Bank reserve assets held in pounds sterling (Fig. 1).

As you can see, by the eve of WWI, in December 1913 (the month the US Federal Reserve crept into existence was instituted), the pound’s share of reserves had slipped a little, with the French franc gaining share but the US dollar was nowhere to be found.

Then came WWI and some interesting things happened.

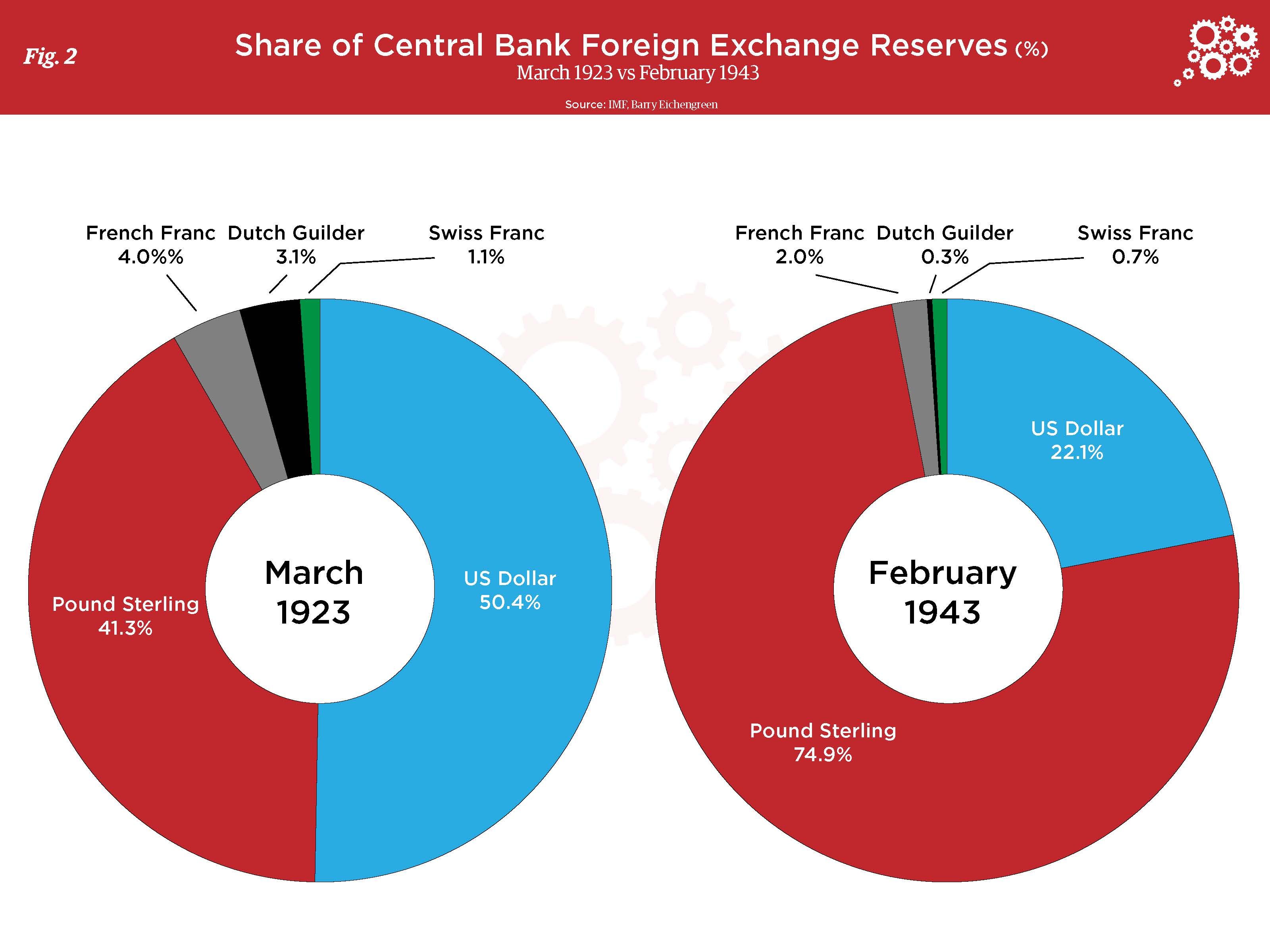

With war raging in Europe, capital understandably fled to the safety provided by the United States—a literal ocean away from harm’s way—dramatically reducing reserves held in sterling and all but eradicating those held in the currencies of mainland European nations (Fig. 2).

However, in the years that followed WWI, the British pound somehow managed to restore its supremacy, and, even in the depths of WWII, the pound accounted for almost three-quarters of global central bank currency reserves—a highly unlikely outcome in the mid-1920s.

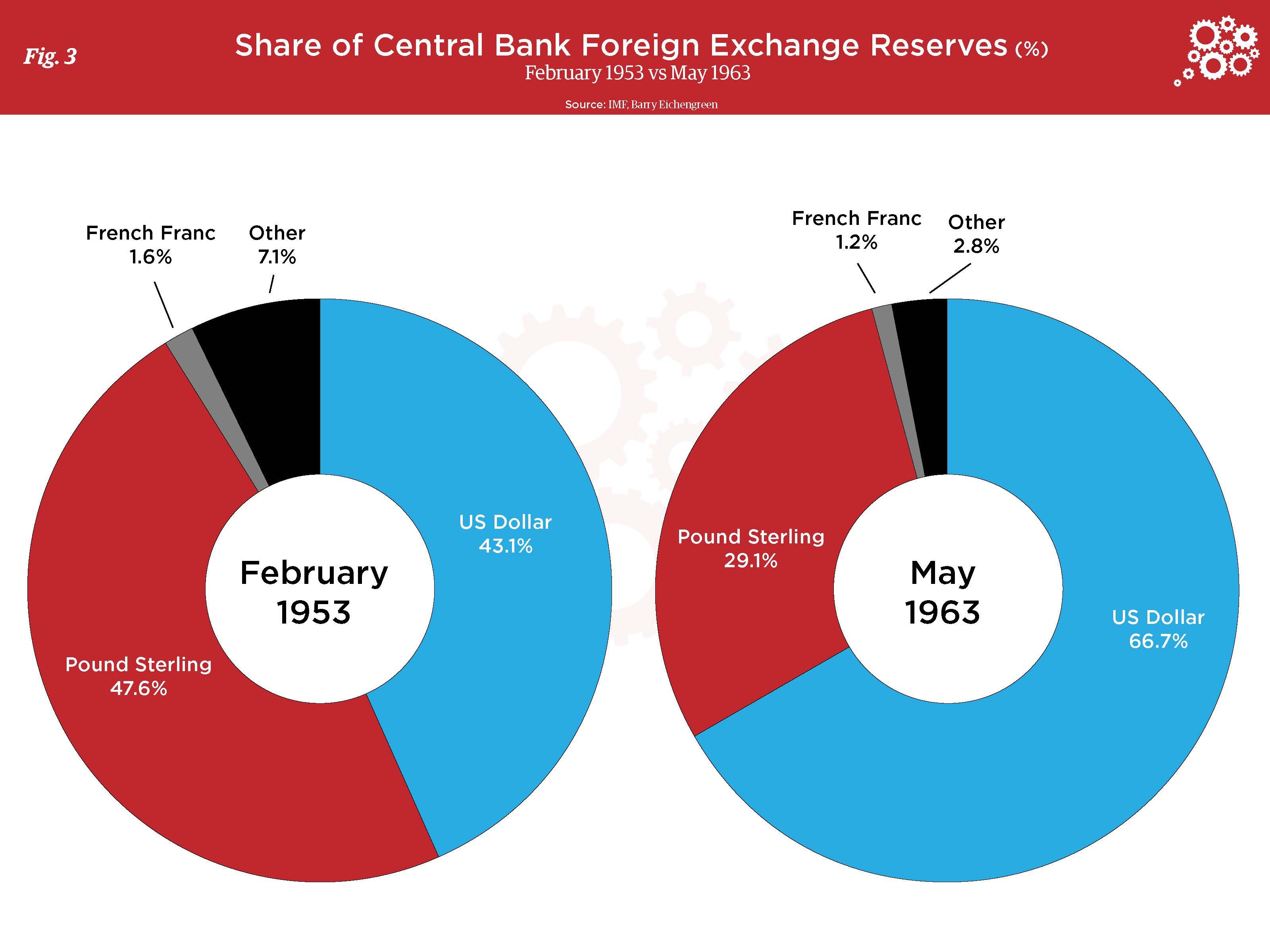

It took The Bretton Woods Agreement in 1944 to cement the dollar’s position at the centre of what was the first (and, to date, only, fully-negotiated) global monetary order. The change, while dramatic, was perhaps not as dramatic as you might think (Fig 3).

In 1953, the pound remained the world’s pre-eminent reserve currency (albeit marginally), but the dollar’s rise was now inexorable and, wherever the tipping point was on adoption, the world was now past it and allocation to the US dollar was accelerating dramatically.

By 1963, the pound, while still constituting almost a third of global currency reserves, was well on its way to borderline irrelevancy, and the dollar was headed for the hegemony with which we are all familiar.

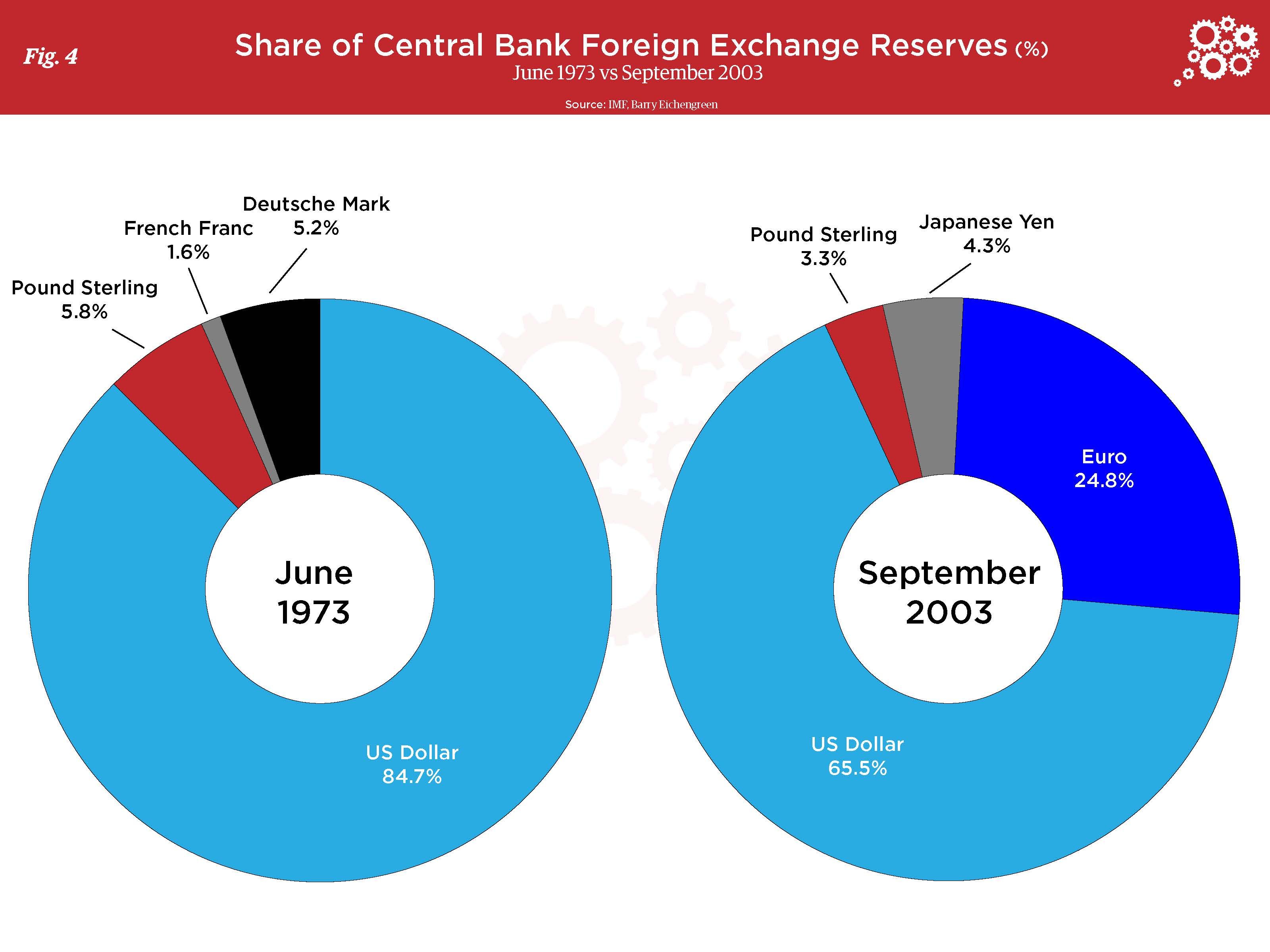

By 1974, with the signing of the petrodollar agreement, the US dollar was the undisputed king of the global monetary order, with a whopping 84.1% of global currency reserves held in US dollars (which is to say, US treasury bonds) (Fig. 4).

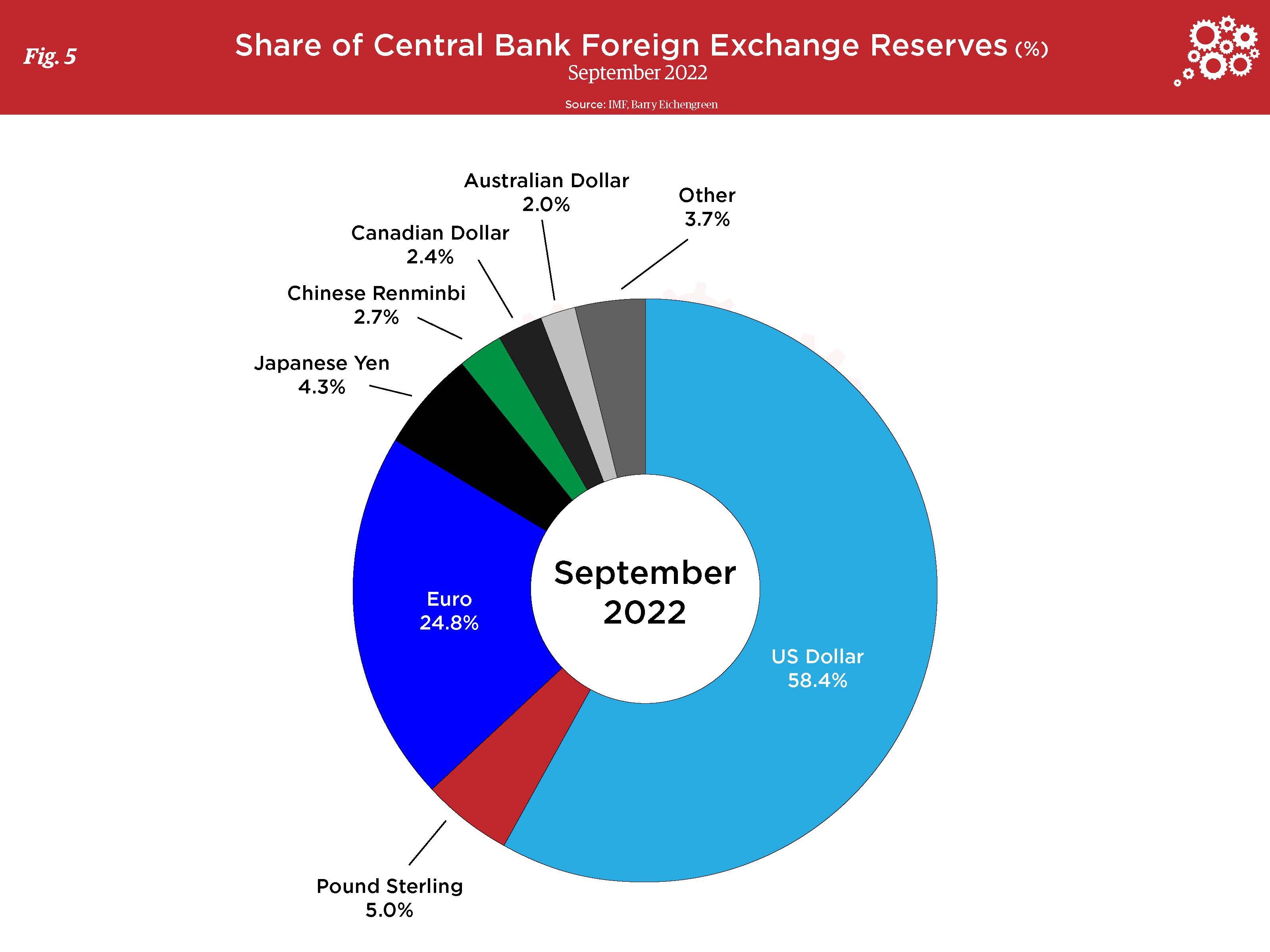

That, however, was the dollar’s apogee, with the euro eating into its dominance after its establishment in 1999, and a broader mix evolving over time as globalisation led to the proliferation of multiple new cross-border trade relationships, many of which needed to find alternative ways to settle and, while the dollar-based SWIFT system still rules international trade settlement, the imperative was clear that alternatives were, if only at the margin, necessary (Fig. 5).

But no matter how it got there, or the ebbs and flows of the dollar’s rise to pre-eminence, it is and has been for decades the biggest, most important, most needed, most ubiquitous settlement and reserve currency on the planet.

Nothing else has come close.

However, the dollar didn’t become the world’s reserve currency because it was imposed by decree or demanded through diplomacy. It became central because it offered something the post-war world desperately needed and couldn’t find elsewhere.

In the aftermath of WWII, vast swathes of the global economy were exhausted. Physical infrastructure had been destroyed, currencies had been destabilised, and capital was scarce. By contrast, the United States emerged from the war with a wholly intact industrial base, vast productive capacity and financial markets deep enough to absorb shifts in global capital without dislocation. Bretton Woods embedded the dollar in daily use. Contracts were written in it, trade was settled through it and capital was stored in it.

The architecture of the global monetary system that emerged after the war did much of the work itself. America offered something no other nation could match: a combination of liquidity, scale, legal framework and institutional stability that made the dollar not merely desirable, but avoidable to almost no one. In time, that usefulness hardened into habit, and habit into assumption. The dollar system was so stable and so omnipresent that its mechanics became invisible to those who relied on it. It simply existed, whether you liked it or not.

This invisibility, paradoxically, was the feature that allowed complacency to grow—not because the system failed, but because it succeeded so well that its continued functioning was taken for granted. Over the decades that followed, no comparable alternative was built, largely because no comparable alternative was needed. Capital markets elsewhere were shallower, legal systems less predictable and political risk, in may places, far, far greater.

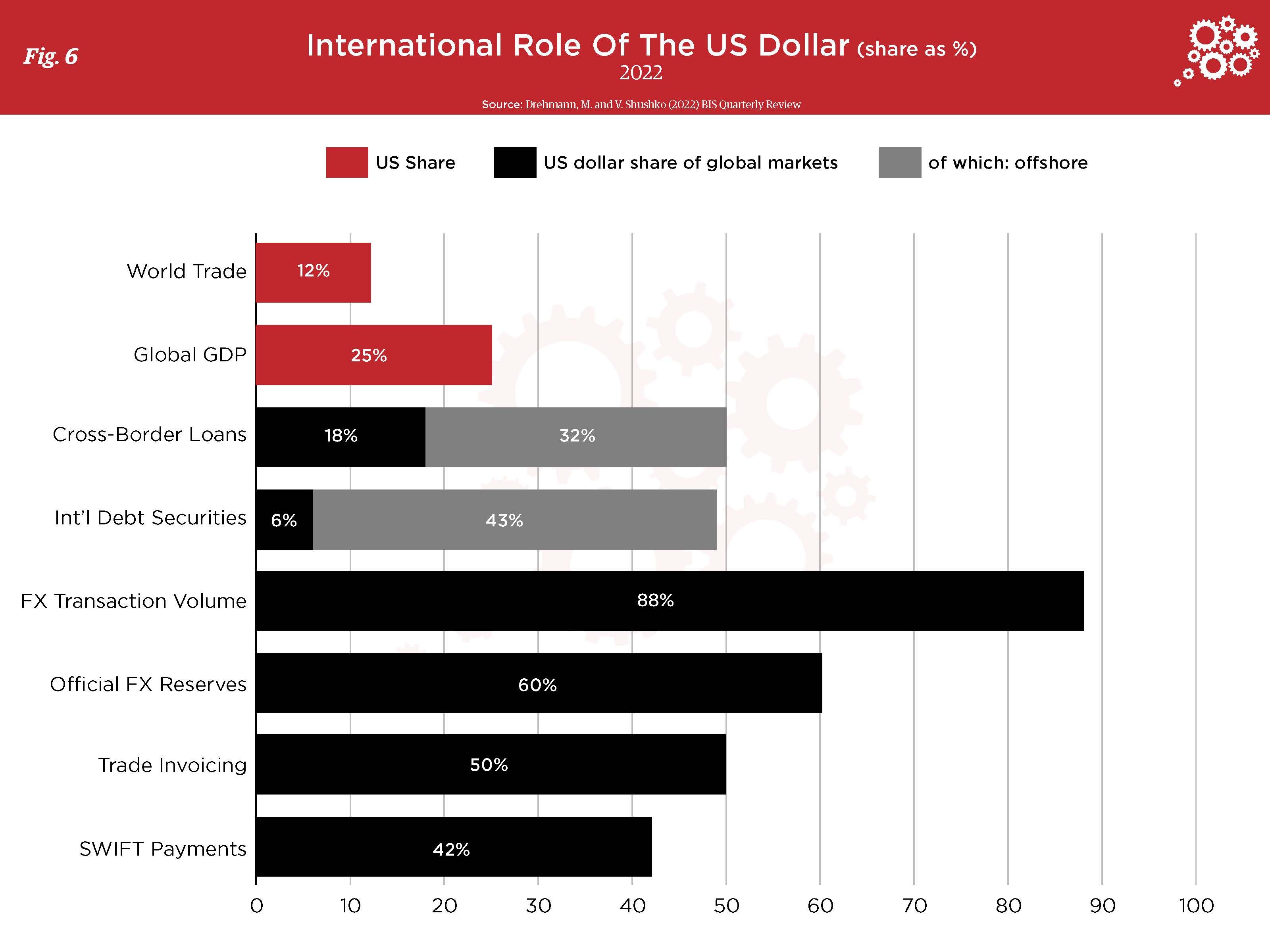

What has shifted in recent years is not that the dollar has suddenly ceased to function. It continues to dominate international trade, global finance and reserve holdings (Fig. 6). Rather, what has changed is the world around it.

The architecture that underpinned American monetary leadership was designed for an era of slower financial flows, clearer ideological divides and more geographically tethered economies. It was built for a world in which capital crossed borders less easily and information travelled less quickly and in which the central role of intermediaries was unquestioned and financial power was anchored to territory.

That world has vanished.

Modern commerce is a creature of speed and complexity. Supply chains now stretch across continents and capital moves instantaneously. In such an environment, the rigidities inherent in older structures such as correspondent banking, deferred settlement and comparatively glacial reconciliation, quickly begin to feel out of place. Yes, they still work, but no longer feel optimal and when systems stop feeling optimal, pressure for alternatives begins to grow.

New payment systems are adopted because they’re faster, new settlement mechanisms are explored because they’re cheaper and bilateral currency agreements begin to proliferate because they reduce risk in a fragile geopolitical environment. The world doesn’t set out to rebel against a system; it simply finds ways to work around inconveniences placed in its way and, over time, those work-arounds accumulate into something more durable.

For years, this transpired largely out of public view, confined to central-bank seminars, infrastructure meetings and experimental pilot programmes. It was boring stuff, the kind only died-in-the-wool technocrats find a way to love. But, unfortunately for technocrats everywhere, history has a habit of dragging the mundane into the spotlight at precisely the moment when its significance can no longer be denied.

That moment arrived, somewhat quietly in March 2022, following the invasion of Ukraine.

When the United States and its allies froze the foreign-exchange reserves of the Russian central bank, the immediate reaction in the financial world was muted. The action was widely described as unprecedented, which it was, but novelty alone rarely makes history. What gave the event its global weight was not the scale of the freeze or even the identity of the target. It was what the action revealed about the nature of modern finance itself.

At the time, I wrote the following about the US Treasury’s move to freeze Russian Central Bank reserves:

TEOTFWAWKI, TTMYGH, March 2022: ...the biggest wave made by the escalating Western sanctions against Putin’s Russia was the move to sanction the country’s central bank — a move that would have far-reaching consequences and, perhaps more than any other action, change the global financial system forever...

One country’s ‘bad incentives’ is another country’s ‘national security concern’. What the West did by excommunicating Russia’s central bank is fire a warning shot across the bow of every other central bank in the world, and it signals the end of an era.

By freezing Russia’s FXreserves, the Westessentially declared open season on anyone they may, at some point, deem a ‘bad actor’ and, while many will argue that they are never likely to merit that label, Russia has proven that’s just not a chance you can afford to take...

My prognosis at the time looks pretty good three years later:

US dollar reserves are set to shrink as central banks diversify themselves away from an asset now weaponized in dramatic fashion.

This will mean a strong bid for gold from price-insensitive buyers in the form of those same central banks. It will also mean that new buyers have to be found for the mountain of US treasury issuance required to not only fund the US government’s out-of-control current spending, but also to pay off the

$168.5 trillion in entitlements due by 2050 as the Boomers continue to retire in their millions (that figure is courtesy of the US Debt Clock and was correct at time of writing but is guaranteed to be low at time of reading).

This will put pressure on the dollar which will, in turn, drive commodity prices higher, demanding higher interest rates if the transitory entrenched inflation is to be tamed.

Yes, inflation has supposedly moderated, but the dollar is under significant pressure and gold has found a solid bid from central banks and, increasingly, the investment community.

But the deeper change unleashed by the freezing of those Russian central bank assets was significant.

For the first time since the modern reserve system had been assembled, a major central bank discovered that its reserves were not simply financial instruments subject to market fluctuations, but political assets vulnerable to external control. What had long been assumed to be a country’s ultimate insurance policy against crisis—access to its own reserve assets—was revealed to be conditional on the ‘correct’ political alignment.

That realisation travelled faster than any headline ever could. What central bankers absorbed in days would once have taken years (and innumerable seminars) to dawn on them. Reserves were no longer to be understood merely in terms of interest-rate exposure and currency mismatch, but in terms of sovereignty risk. The distinction, long treated as theoretical, became immediate and practical.

For decades, reserve management had been framed as a technical discipline insulated from geopolitics, possessed of it sown language, its own models and its own culture, with ‘risk’ merely something to be hedged through diversification and yield optimisation. Moreover, political instability was discussed in the abstract, but rarely treated as something that could directly affect access to assets held in the reserve portfolio. Central banks prided themselves on neutrality and, whether that pride was ever fully justified, matters far less today than the undeniable fact that it shaped behaviour.

The freezing of Russian reserves shattered that perception in a single act. It demonstrated that the system, however sophisticated, was not neutral infrastructure, but rather policed space. It contradicted decades of unspoken assumption that central bank money sat above political conflict and, in that instant, reserves became visibly and overtly political capital.

That, Dear Reader, is everything.

There was no dramatic exodus from the dollar that followed. No mass divestment, no public rebuke, no currency crisis triggered by political anxiety.

Yet the impact of that single, politically-motivated action was profound. The conceptual framework used to understand reserve assets changed instantly, and when frameworks change, behaviour always follows—even if it does so quietly.

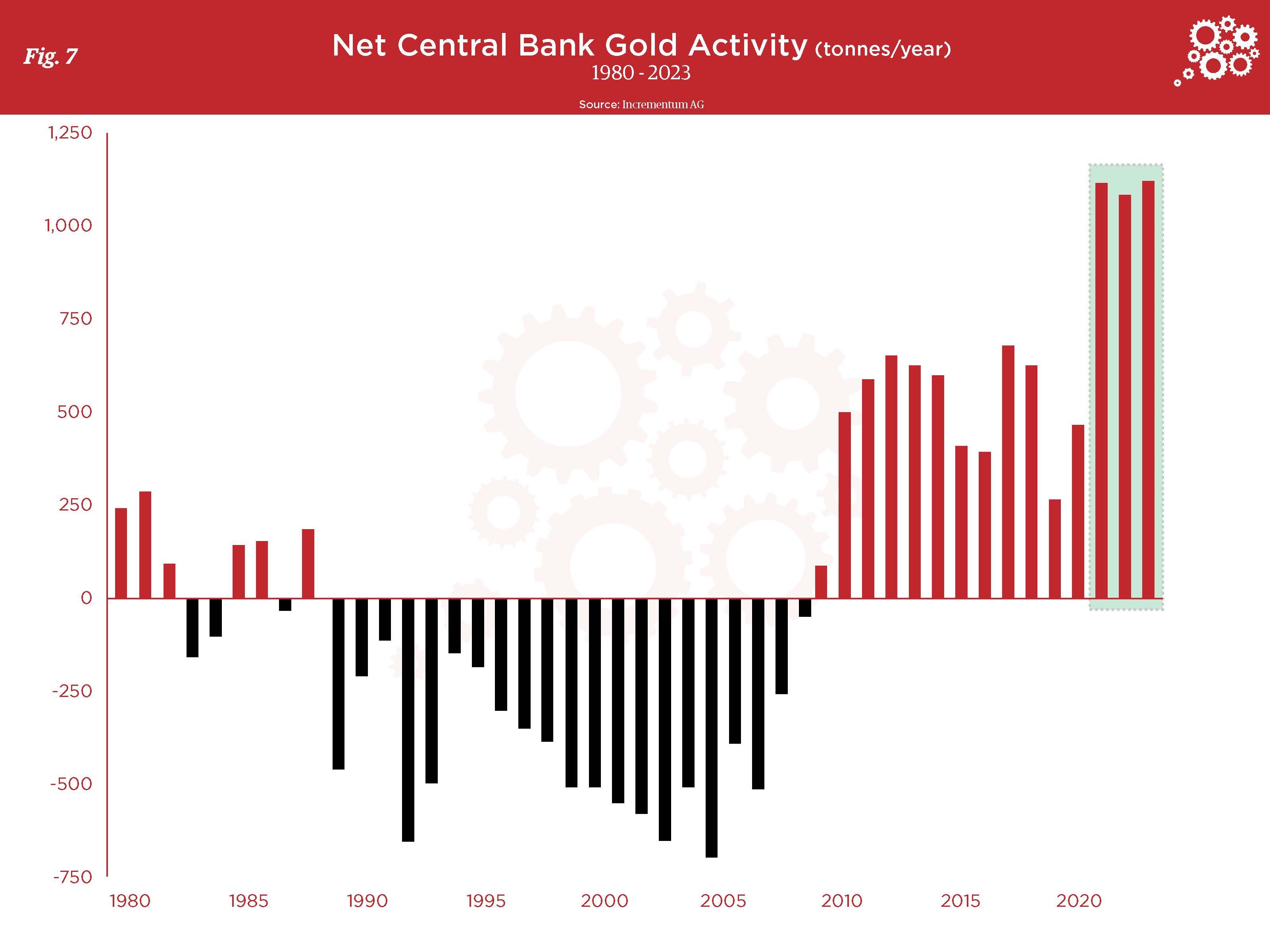

In the months that followed, central-bank balance sheets began to tell a more revealing story than any statement ever could. Official purchases of gold accelerated to levels not seen for a generation (Fig. 7) and, while some of that could be explained through inflation concerns or routine diversification, the sheer scale and persistence of buying pointed to something much deeper, much more profound. Gold wasn’t being accumulated because it offered yield, but because it offered independence and security.

Unlike sovereign bonds, gold bears no counterparty risk. It exists outside the digital permissions structure that governs modern finance. Assuming it is secured under a given country’s own auspices, it can’t be frozen, defaulted upon or rendered inaccessible by administrative decree. It’s economically awkward, politically inert and operationally unfashionable, which is precisely what made it instantly relevant again.

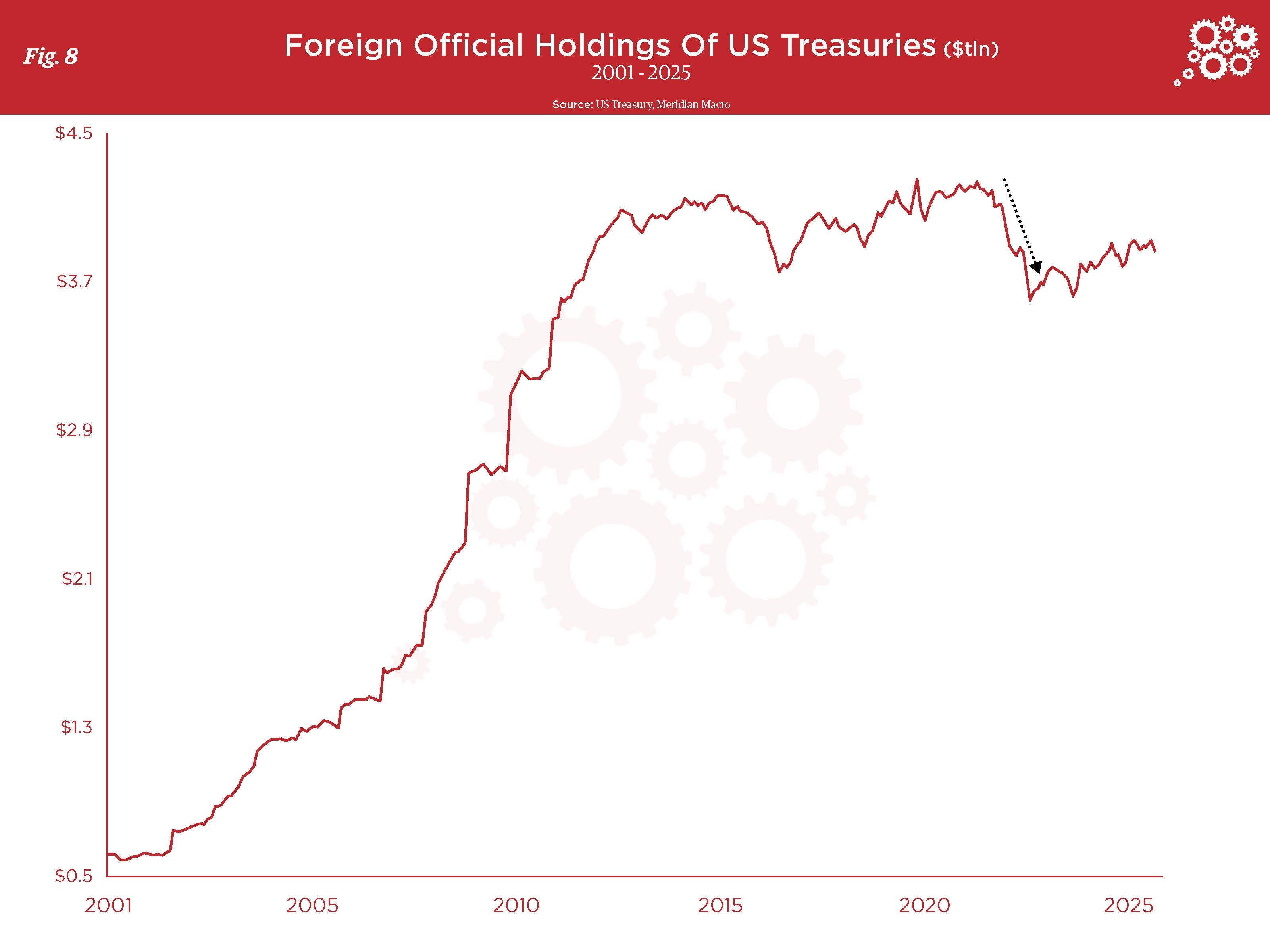

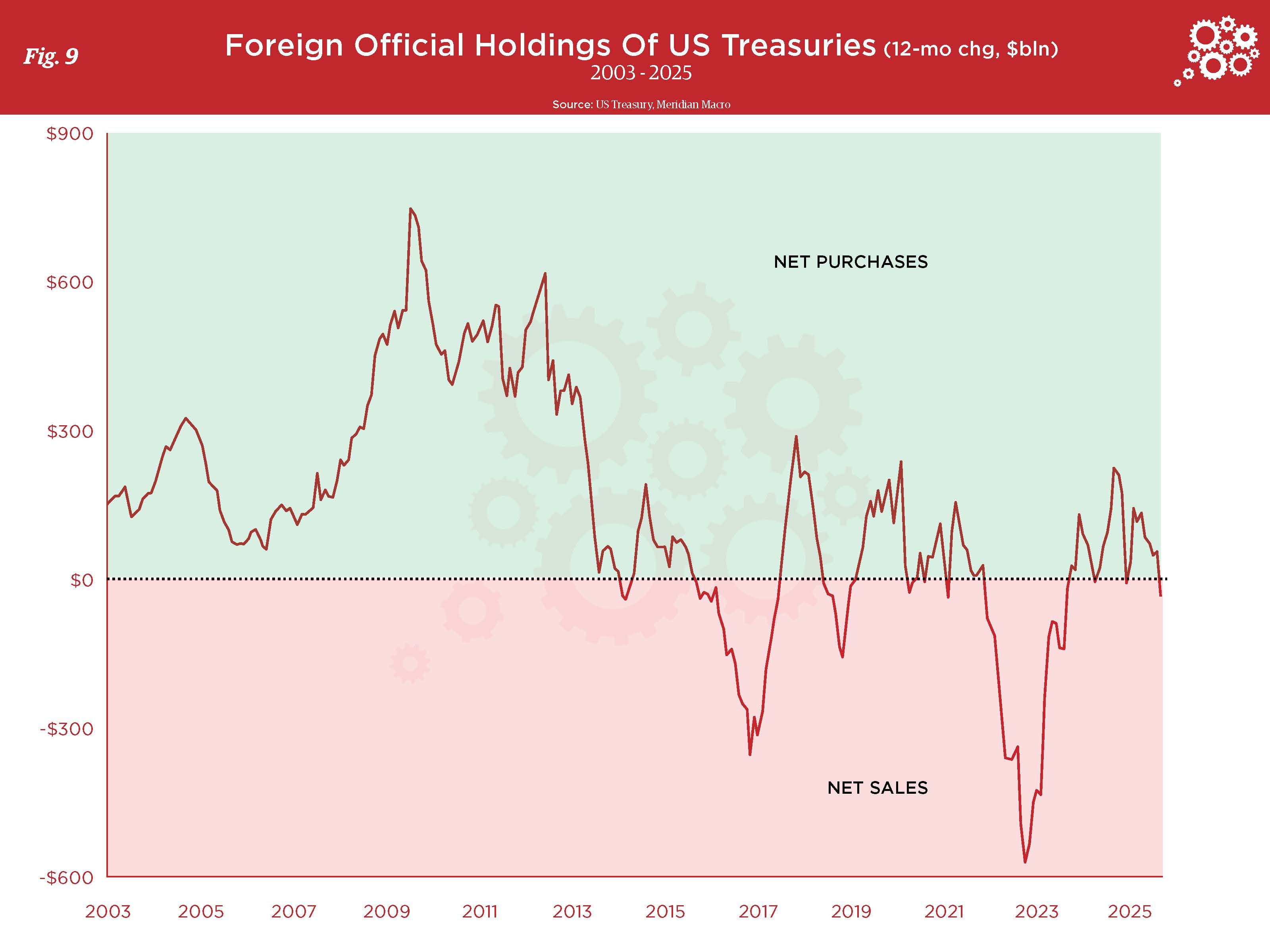

At the same time, holdings of US Treasuries began to flatten in certain jurisdictions and decline in others (Fig. 8 & 9). This wasn’t so much a judgement on American monetary policy, nor a sudden loss of faith in the Federal Reserve but, rather, hedging in its purest form. The moment the structural assumption of political sanctity on sovereign reserves fell was swept away, portfolios needed to be adjusted. It wasn’t a matter of choice.

It would be wrong to interpret these moves as rebellion or protest. Buying gold and quietly offloading treasuries at the margin simply offered an insurance policy, purchased quietly and incrementally, with the objective not the dismantling of the existing system, but a reduction of dependence upon it.

That single decision by the US Treasury didn’t destroy the dollar’s role, but it did alter its psychological character, and the timing of that alteration was crucial. What had once been understood as neutral infrastructure was now visible as politically governed system and, once that recognition sets in, the relationship between user and custodian inevitably shifts. Crucially, throughout the period of US dollar hegemony, there was no real competition—or, more accurately, no real competitor. But now a rival was waiting in the wings in the shape of a rising China.

History suggests that confidence rarely collapses neatly. It thins, adjusts, and moves sideways before it moves away and, in the case of global reserve systems, they don’t disappear overnight. Instead, they get diluted gradually through a series of marginal decisions—and the occasional catastrophic misstep.

To understand the shape that path eventually takes, we needn’t speculate. History provides a useful template, beginning in the Summer of 1956.

Suez is remembered popularly as an episode of imperial hubris, a late and clumsy attempt by Britain and France to impose authority in a post-colonial Middle East. But it’s far more useful to understand it as a monetary event disguised as a geopolitical one, the final revelation of something that the world already knew to be true—that Great Britain no longer remained financially sovereign.

For more than a century before Suez, sterling had been the connective tissue of global commerce, with London not simply a marketplace, but the mechanism through which the world’s trade, credit, and insurance were conducted. The British Empire, at its height, was not only territorial but financial; it ruled shipping lanes and capital markets with equal assurance, and the pound reflected that reach in its function as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account on multiple continents. Confidence in sterling didn’t arise from patriotic sentiment, but rather from the City of London’s institutional strength, predictable law, deep markets, and an aura of continuity so established that it eventually became invisible to those who benefited from it.

Sound familiar? Thought it might.

Beneath the surface, however, two world wars had altered the mathematics of Britain’s dominance far more than the status quo suggested.

Britain emerged from WWII no longer the world’s banker but as its debtor-in-chief, burdened by loans, dependent on American support, and presiding over an industrial base that no longer led the world it had once supplied.

Sound familiar? Uh huh...let’s continue...

Reserve systems rarely respond to a hegemon’s weakened fundamentals in real time. Instead, they take their sweet time, sustained by confidence and familiarity long after confidence has become more hope than reality.

The Suez Crisis brought that misalignment into sudden and unforgiving focus.

When Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal in 1956, London and Paris interpreted the act in political terms and responded militarily, convinced that this was a challenge to their elevated standing in the world order that could only be restored through force. What they misjudged was not the tactical complexity of the operation, but the dimension in which it would be decided. The crisis was not settled in Egypt. It was settled in financial markets.

The United States, concerned less with the canal than with the stability of the post-war order (oh-so-close to the centre of which it happily sat). Sensing a moment which would allow it to improve its own position by weakening that of its ‘allies’, it reneged on the ‘special relationship’ it had with Great Britain, making plain that it wouldn’t provide financial support to sustain an imperial enterprise it no longer endorsed.

Like the Russians in 2022, all four countries involved in the Suez Crisis (Great Britain, France, Egypt and Israel) discovered almost immediately what that decision meant in practice.

Here, courtesy of the IMF, is a potted history of the crisis for those among you unfamiliar with what is a chronically under-appreciated event in global monetary history:

On July 26, 1956, Egypt nationalized the Suez Canal Company and unilaterally assumed control of the canal from the international consortium that had run it for nearly a century. France, Israel, and the United Kingdom almost immediately began planning a joint military action to retake control, while they sought to win international support for a diplomatic solution. When diplomacy failed, Israel invaded the Sinai on October 29, and France and Britain used Egypt’s counterattack as an excuse to attack Egypt by air from the Mediterranean two days later. The fighting shut down the canal, which was the major shipping channel between Europe and Asia and a vital link in the transport of petroleum from the Middle East. One week later, however, Britain undercut the operation by accepting a United Nations resolution for a ceasefire. On December 3, the British government announced that it would withdraw its troops over the next few weeks. France and Israel soon also withdrew, and Egypt reopened the canal under its own control the following April.

That’s what happened. Here’s why it mattered:

That this brief flare-up is universally regarded as a crisis is primarily because of the upheavals it engendered in political relations. It successfully climaxed Egypt’s longstanding campaign for full independence from European dominance. It demonstrated Israel’s ability to defend and expand its borders militarily and thus to survive as a nation. It weakened France just as the Algerian war was intensifying. It exposed a rift in relations between Britain and the United States over post-colonial policies at a time when both wanted to counter the rising regional influence of the Soviet Union. In Britain, it brought a sad end to the brief ministry of Anthony Eden and ironically elevated Harold Macmillan in his place. In view of the central place of Suez in the mythology of the British Empire—Eden had once called it “our back door to the East,” and generations had grown up on Kipling’s evocation of an uninhibited life “some-wheres east of Suez”—the loss of control over the canal was devastating for those with lingering Victorian aspirations. In the Middle East, it solidified Gamal Abdel Nasser’s budding leadership role and hinted—if only temporarily—at the possibilities for Arab unity. A vast and still-growing literature has analyzed each of these facets in exquisite detail.

But beyond the politics of the Suez Crisis, lay the more important, more lasting damage.

Interestingly, the IMF’s assessment of the economic damage done by the crisis was fairly benign:

The economic consequences of Suez were more subtle and temporary and would not by themselves have constituted an international crisis. Notwithstanding the crucial importance of the canal for certain trade flows, the economic impact of its closing was limited by its short duration. By October, Egypt had already proved that it could run the canal safely and efficiently without European assistance. For the six months that the canal was closed, the resulting cost increases, delivery delays, and trade diversion weakened the current account positions of all four of the combatants, but normalcy was largely restored within another six months.

No biggie, right? Wrong.

Egypt, Israel and France each went, cap-in-hand to the IMF, and were granted loans to help them through the turbulence created by Nasser’s actions.

Great Britain, her stiff upper lip firmly set, soldiered bravely on until she too was forced to seek help and the events of 1956/7 when viewed exclusively from the British perspective are vital to understand.

In the summer of 1956, Britain had entered the Suez drama from a very different position to France, Israel and Egypt. On the surface, its external accounts looked sound. While France and Israel were watching their current-account positions deteriorate sharply and Egypt faced the loss of canal revenues, the United Kingdom was running a respectable surplus: £159 million in the first half of the year, rising to a total of £245 million for 1956, with a similar outcome in 1957.

However, the problem lay not in the trade numbers, but in the psychology of markets that watched sterling as a reserve currency with a published reserve floor of $2 billion and a fixed parity of $2.80 to the US dollar that the authorities believed they must defend. Once Suez erupted, the question became not whether Britain could pay its way, but whether it could hold that rate without external help.

For British policymakers, the $2.80 parity, set in 1949, had acquired totemic significance. It was deemed appropriate for trade, and crucial at a moment when the closure of the canal threatened to force the UK to pay ‘expensive dollars’ for diverted oil imports.

More profoundly, maintaining parity was seen as essential to preserving the pound’s wider role as a reserve currency. A problem for Great Britain, an opportunity for the United States.

Although sterling was not yet fully convertible post-WWII, capital controls were patchy, and the currency was widely held abroad, making it uniquely vulnerable to speculative pressure in a way Egypt’s or Israel’s currencies were not. Falling through the self-imposed reserve floor, clearly visible in the monthly figures, would be read in markets as a signal that devaluation or floating could no longer be avoided. In that context, the Suez Crisis didn’t merely threaten British foreign policy, it threatened the credibility of Britain’s money.

Harold Macmillan at the Treasury and Cameron Cobbold at the Bank of England were united in seeing any devaluation as catastrophic. They regarded a second devaluation, a mere seven years after that of 1949, as something that would risk breaking up the sterling area, undermine the nascent European Payments Union, shrink trade and unleash domestic inflation. In Cobbold’s words, it was a “disaster to be fought with every weapon at our disposal.”

Macmillan agreed.

Both understood that the $2.80 rate could not be held without American support, and that such support was unlikely while Britain was defying Washington over Egypt, yet they still refused to contemplate either devaluation or a float. In effect, they made defence of the parity non-negotiable, even as they launched a military operation that placed sterling under maximum strain.

When Nasser nationalised the canal on 26 July 1956, the Bank of England had already prepared for trouble with plans to block Egyptian accounts. When selling pressure on sterling materialised, officials initially assumed that Egypt was dumping its holdings, and they responded by freezing transfers between sterling and the Egyptian pound. But this gesture did nothing to stem the broader speculative pressures.

Over the next four months reserves declined steadily toward the $2 billion floor, temporarily held above it only by a lucky inflow of $177 million in September from the sale of the Trinidad Oil Company to, of course, an opportunistic American buyer.

The Bank’s first line of defence was direct intervention in the foreign-exchange market, buying sterling against dollars, while dismissing the classic response of raising interest rates as ineffective in a crisis of confidence. But, when a central bank is forced to intervene directly in FX markets, all participants know the game is up. It’s just a matter of time.

Behind the scenes, Macmillan was seeking a second line of defence. Confident in the ‘special relationship,’ between Great Britain and the United States, and bolstered by his own personal ties to the US, he assumed hoped Washington would step in to support sterling by waiving interest on wartime lend-lease debts or providing fresh loans through the Export–Import Bank. Failing that, he fully expected that the IMF would provide substantial support, both because Britain had the second-largest quota and because it held a supposedly unique importance as a founding member.

The IMF and World Bank Annual Meetings in Washington at the end of September offered the obvious moment to test the waters.

Macmillan, attending as Britain’s Governor, met US Treasury Secretary George Humphrey, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and President Eisenhower, came away with the impression that some form of US financial support would be forthcoming after the November presidential election. He returned to London convinced that his American counterparts would not leave sterling undefended.

Hmmm...

Through October, as the Bank continued to run down its reserves and the Cabinet prepared for war with Egypt alongside France and Israel, Macmillan took no further decisive steps. When Israel invaded Sinai on 29 October and Anglo-French bombing began two days later, US and international opposition hardened, and the drain on British reserves accelerated into a genuine speculative attack. On 2 November, the UN General Assembly passed a US-sponsored resolution calling for a ceasefire; within days the pressure became intolerable.

By early November, it had become clear that financial forces were driving British policy, forcing capitulation. The Cabinet agreed to a ceasefire on 6 November under intense diplomatic and market pressure, and Macmillan later conceded that the US refused to support Britain’s request to draw on the IMF until London had accepted a ceasefire and, in practice, full compliance with the UN resolution, including withdrawal of troops.

Once that political condition was met, attention returned to assembling a package large enough to convince markets that sterling could withstand attack. Cobbold resisted approaching the IMF immediately, fearing that it would signal weakness unless part of a broader support arrangement, while officials in the Treasury suspected the Fund was their only real hope. Both agreed that if they went to the IMF they should seek the maximum possible credit, up to three tranches, or 75% of Britain’s quota, a sum unprecedented for a major country.

Britain’s weakness had been exposed, the US realised it had the upper hand and like any good ally, it stepped on Great Britain’s neck.

Through November, technical consultations with IMF staff in London continued at a routine level, but the real decisions were being taken in Washington. Per Jacobsson, the incoming Managing Director, was persuaded during a stop in London that Britain’s exchange rate was ‘fundamentally sound’ and that a major package was justified to defend sterling and protect the wider system. On taking office in early December, he resolved that the UK should receive a total of around $1.3 billion. At the same moment, Humphrey was wrestling with the fear that a large IMF operation for Britain could trigger either a run on the Fund or higher US interest rates, but eventually reversed himself, concluding that the best way to restore confidence was to go big: Britain would draw half its quota immediately and secure a stand-by for the rest.

On 3 December, with British reserves about to fall below the symbolic $2 billion floor, London finally had its answer. The United States signalled support for a large IMF operation, on condition that Britain conformed to the UN line, and the Fund’s Executive Board approved a drawing of $561 million with an additional $739 million available on stand-by.

Macmillan was able to go to the House of Commons on 4 December, announce the heavy loss of reserves in November, and simultaneously unveil a rescue package designed to ‘fortify’ sterling. The very fact that the IMF and the United States were now standing visibly behind the pound was enough to halt the immediate run. Reserves stabilised above the floor and, although Britain later renewed the stand-by in 1957 as policy doubts resurfaced, it never had to draw the remaining funds. The episode demonstrated, more clearly than any speech could have done, that British power in 1956 depended less on tanks at Suez than on credit in Washington.

The events surrounding the Suez Crisis were hugely important because they demonstrated how, at the appropriate moment, even the world’s hegemonic currency can be toppled when ambition collides with opportunity.

Britain, while still a major power, was economically fragile in 1956 and, in the end, that fragility was exploited by the US to usurp Britain’s place at the top of the global monetary order.

The United States manufactured the moment in which the world understood Britain could no longer guarantee its own currency without external patronage. From that point onward, sterling’s authority rested not on its own credibility, but on borrowed confidence.

Nothing in the visible world had broken. Markets opened, trade continued and London remained busy. Yet beneath that continuity, something decisive had occurred. Central banks and international institutions did not record the end of sterling’s reserve status on that day. But they began, quietly and pragmatically, to act as though it had.

Confidence didn’t collapse, it simply reorientated itself in real-time.

Reserve managers trimmed exposure, contracts were increasingly denominated elsewhere and the dollar expanded into roles the pound had once filled.

Suez, in this sense, should be read less as an episode of diplomatic miscalculation and more as a stress test that Britain failed. The British Empire didn’t fall because it lost a canal, it fell because it lost financial independence, and with it the ability to convert ambition into action without asking for permission from its ‘friends’ in Washington.

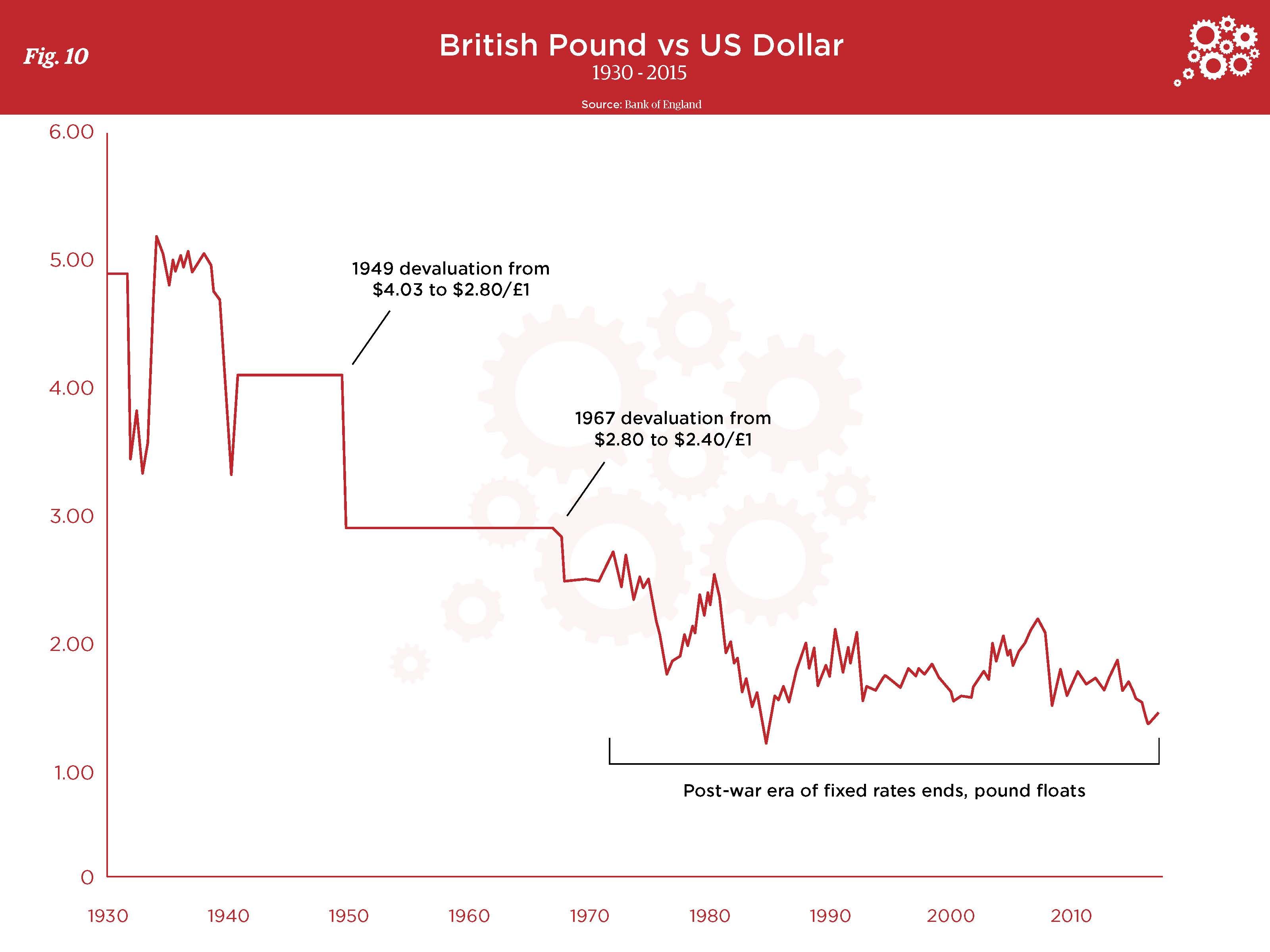

In the decades that followed, Britain suffered through wage restraint, repeated devaluations (Fig. 10), balance-of-payments crises, and recourse to international lenders whose involvement would once have been unthinkable. The privileges that came with issuing the world’s reserve currency—the capacity to borrow without consequence, to finance conflict without currency risk and to absorb capital without distortion—had quietly disappeared. Britain didn’t become poorer overnight, but it became constrained, and that was the death knell for sterling as the backbone of the global monetary system.

The lesson embedded in Suez is not simply that currencies can die when politics goes wrong, but also that monetary authority collapses the moment capital decides it’s no longer safe to rely upon it.

This is what makes Suez so uncomfortably relevant to the present.

Suez didn’t kill sterling, it merely removed the ability for its trading partners to wilfully ignore its frailty.

Sound (potentially) familiar? On we go...

Suez quietly marked the moment at which the architecture of a new system completed its consolidation. The groundwork had been laid long before British ambitions collided with mathematics in the Eastern Mediterranean. Bretton Woods, designed in the closing years of war, had already mapped the contours of a world in which American capital and American institutions would form the structural spine of global finance. Suez simply made clear that the transition had already occurred in substance if not yet in symbolism.

What distinguished the American rise from every reserve-currency episode that preceded it was not merely scale, but timing. The United States became the world’s monetary anchor at the precise moment the world was rebuilding itself. Capital scarcity in Europe and Asia created infinite demand for liquidity, while destroyed infrastructure guaranteed demand for investment. America alone possessed reserves, industrial capacity, and institutional coherence at sufficient scale to fulfil those needs simultaneously.

In earlier centuries, reserve currencies grew alongside empire, secured, for the most part, by maritime dominance and reinforced through colonial trade networks. The dollar rose through reconstruction, international lending, and market architecture rather than conquest. In funding Europe through the Marshall Plan, the United States exported both money and confidence, embedding its legal norms, economic assumptions and commercial standards into the rebuilding of an entire continent. As they circulated, dollars became the foundation of recovery itself.

By establishing a global standard anchored to convertibility into gold and discipline (at least in theory), Bretton Woods offered the world a financial lubricant that appeared neutral, even as it was deeply American in design.

Ultimately, it was, and remains, nothing of the sort.

Currencies remained nominally sovereign, but they orbited a system whose centre of gravity lay unmistakably in Washington and New York. For a world exhausted by inflation, disorder and war, stability was not merely welcome, it was intoxicating.

Yet the greatest achievement of the post-war system was not its architecture but its psychology. It didn’t require enforcement to persist because it operated through the complete acceptance of its members.

Nations held dollars because they worked, transacted in dollars because so many others did (in large part, thank to the 1974 petrodollar agreement), and invested in America because American markets offered depth and continuity unavailable elsewhere. No other country could combine rule of law, entrepreneurial capital, and political continuity with such credibility at scale.

Global trade spoke the language of the dollar not because it was demanded, but because it was ubiquitous and this ubiquity proved far more durable than any treaty.

But it was precisely that ubiquity, rather than any dollar dominance, which turned what began as a preference into complete dependence.

Systems that function well for long periods breed confidence, and confidence eventually becomes a toxic mixture of complacency and entitlement. For decades after Bretton Woods, America benefited not just from issuing the world’s money, but from writing the conditions under which money itself was defined. Legal frameworks, accounting rules, capital requirements and compliance standards flowed outward from the United States alongside dollars. Finance, in effect, converged around mostly American assumptions.

But convergence carries its own risks.

When all liquidity passes through the same pipes, the failure of any segment becomes systemic by definition, and when regulation and settlement are concentrated under one jurisdiction, political risk and financial risk cease to be distinct.

Over time, this concentration would prove to be perhaps the dollar-based financial system’s greatest strength...however, with the actions of March 2022, it has proven to be potentially its greatest vulnerability.

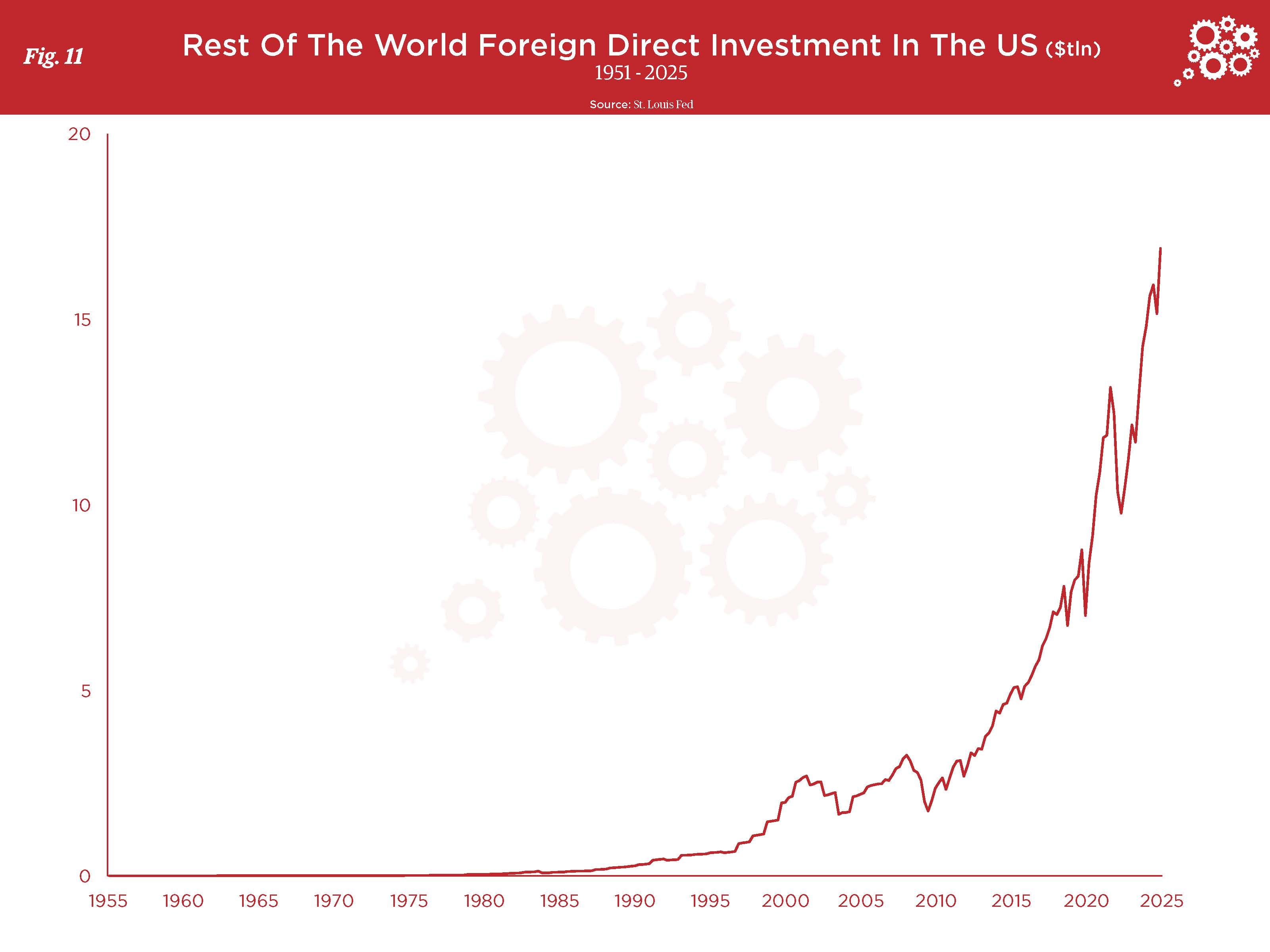

For decades the system worked remarkably well. Inflation, once banished, appeared vanquished, and capital surpluses flowed obediently into American assets (Fig. 11), allowing the United States to consume far more than it produced without visible strain.

Financial innovation multiplied, credit expanded and the American consumer became the global engine of demand and the global absorber of surplus.

And, for as long as the system held, it delivered extraordinary results.

There was, however, a subtle inversion taking place beneath the surface.

The dollar’s role as the world’s most important money currency gradually and, imperceptibly altered the incentives that once sustained it. As easy financing muted fiscal discipline and capital inflows distorted domestic asset prices, Wall Street grew ever larger, ever more elaborate, and increasingly detached from the real economy beneath it.

Meanwhile the industrial heart of the United States thinned as production moved offshore in pursuit of lower costs, migrating to the very nations whose surpluses would ultimately return to American capital markets as lending.

For decades, ‘globalisation,’ as this wave became known, looked for all the world like it brought nothing but benefit, and yet, beneath its surface, the tide carried consequences that no one either expected, or expected to matter.

Each generation not only inherits the system as it exists, not as it was built, but forgets the assumptions that once made it reliable and drifts farther away from its intended purpose as a new generation of politicians promises and spends—abusing the exorbitant privilege bestowed upon the issuer of the world’s reserve currency at any (and, sadly, every) point in time.

The system endured nonetheless, absorbing shocks with impressive resilience. Oil crises, currency panics, and financial busts came and went. Latin American crises flushed through Wall Street and cleared. The Asian financial contagion of the late 1990s tested liquidity, but reinforced rather than weakened America’s centrality. Even the Global Financial Crisis failed to unseat the dollar, in part because the only asset considered safe at a time when toxic American credit threatened the system’s stability was the currency in which the vast majority of that debt was denominated.

Go figure.

What that episode truly demonstrated was not merely the inertia of dollar dominance, but the degree to which the rest of the world would tolerate imbalance rather than experiment with alternatives. Countries whose reserves had been annihilated through the crisis nonetheless returned to the system they already knew.

Better the devil you know.

And yet, even though it’s never immediately obvious, each crisis subtly changes what participants are willing to accept next time around. This is one of the great paradoxes of monetary history. The longer a system survives, the more fragile its assumptions become.

At no point did the American system appear to display visible weakness. What it did instead was evolve into something too large, too interconnected, and too essential to fail easily or, importantly, change quickly.

This is why the emergence of possible alternatives over the last decade didn’t resemble any kind of revolt.

The BRICS seemed are disorganised and, some believe, innocuous, but they hijacked the debate and hardened the position taken by both sides: either the dollar is dead, or the BRICS are a nothingburger.

There’s nothing in-between. Or so it would seem...

Meanwhile, in the background, China began constructing its own payment infrastructure as protection against the dollar’s increasing weaponization—not as a challenge to its hegemony. Energy exporters sought currency diversity as insurance and smaller nations built settlement options not as retaliation, but as both resilience and redundancy. None of this required coordination because it emerged naturally thanks to shared interests, and beneath it all sat the reality that the system, while formidable, had begun to show its age.

If Britain lost reserve leadership when it could no longer defend sterling alone, America now faces a far subtler dilemma. Its system remains dominant, but dominance is no longer exclusive. For the first time since Bretton Woods, the world is building around the dollar rather than simply through it.

Importantly, the nature of that dominance isn’t Bretton Woods alone, nor even American industrial might, but the evolution of a system that turned trade imbalances into financial fuel.

The world didn’t merely adopt the dollar as a medium of exchange. Through the petrodollar agreement, it accepted, largely without debate, an arrangement in which the accumulation of surplus in one part of the globe automatically financed consumption in another. In this circular flow of capital lay the true engine of American influence, an influence rarely described accurately because its workings were neither ideological nor explicit.

Nowhere was this more evident than in energy markets, which, of course, sit at the base of modern economic life. Oil pricing in dollars was possibly not initially conceived as a grand instrument of empire, but likely more as a convenience that simplified trade among producers and consumers scattered across continents. Over time, however, petrodollars didn’t simply exist as accounting entries on contracts; they accumulated, and then, crucially, returned home in the form of treasury purchases.

Energy exporters found themselves awash in dollars, as an operational outcome. With limited domestic capacity to absorb that inflow in a productive way, those surpluses sought a home, and American capital markets offered a refuge that no other destination could match at scale. Thus was born the great recycling mechanism that underpinned late-twentieth-century American prosperity: oil revenues flowed outward, and financial claims flowed back in.

This system achieved something few trade structures ever manage. It harmonised the interests of producer and consumer through inertia rather than negotiation. Energy exporters enjoyed largely stable dollar revenues, the United States financed excessive wanton consumption through foreign savings, and global imbalances, rather than causing breakdown, fuelled continuity.

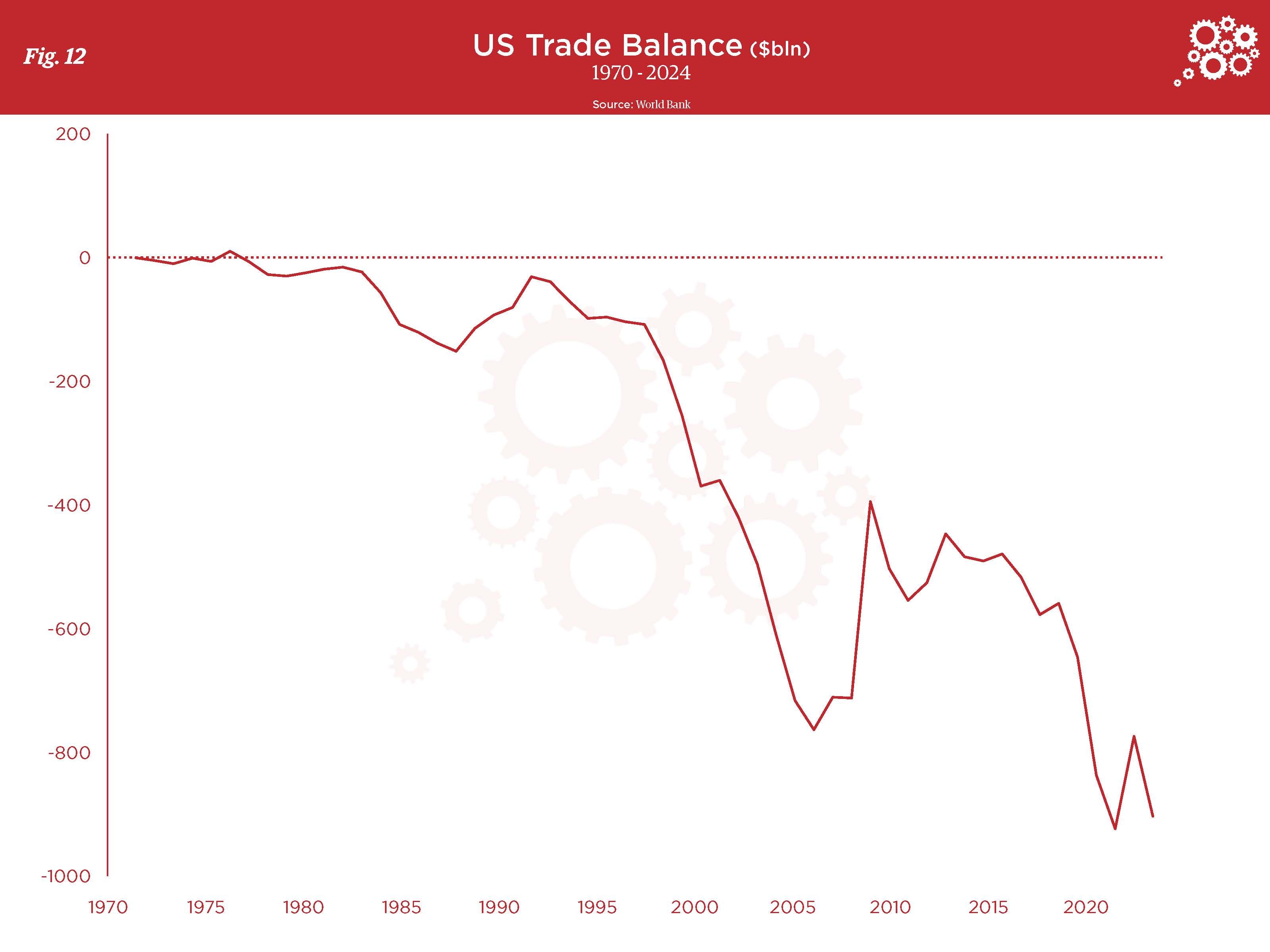

It’s difficult to overstate how extraordinary this arrangement proved to be in practice. For decades, America lived with persistent trade deficits that in any other historical context would have provoked some kind of a crisis (Fig. 12). Yet remarkably, these imbalances were not merely tolerated by foreign governments, they were actively financed by them. The very nations exporting goods and energy to the United States reinvested their earnings into American debt, equities and assets, completing a financial circuit that rewarded all participants in the short term while quietly altering the structural incentives of the system.

The effects were visible but poorly understood.

Consumption expanded, asset markets rose, and borrowing costs fell. Meanwhile, American policymakers grew accustomed to deficit financing without penalty, and American consumers learned to expect ever-cheaper abundance unconstrained by production.

What went unnoticed ignored for far too long was that this system didn’t merely reflect American strength. It actively reshaped it.

Easy financing dulled fiscal restraint and persistent capital inflows inflated financial assets faster than wages as the country’s manufacturing base was offshored. Meanwhile, finance expanded inward and political promises became easier to make because the hard choices associated with funding them were always deferred to the future.

The world didn’t conspire to perpetuate the dollar system. It allowed it to continue to exist because it functioned, and because in the early decades it had delivered growth that felt universal enough to be defensible. The post-war boom, fuelled by reconstruction and consumption alike, created an atmosphere in which debt appeared benign and trade imbalances seemed harmless. As long as everyone was growing, no one wished to examine the machinery too closely.

By the turn of the new millennium, however, the fragilities had begun to emerge. Asset prices disconnected from income as credit expanded completely out of step with productivity and financial complexity accelerated at breakneck speed.

Incredibly, the Global Financial Crisis didn’t break this arrangement, despite its epicentre being squarely in the United States. If anything, it reinforced it.

In the midst of chaos, capital fled not away from the dollar but toward it, teaching governments across the world that, while American finance had grown dangerous, it remained indispensable and, when the system convulsed, it was American liquidity, supplied in abundance by the Federal Reserve, that stabilised it.

What the emergency programmes of 2008 and beyond truly demonstrated was not merely the necessity of central intervention, but the extent to which the system had come to rely upon it, and with each successive rescue, the line between extraordinary and routine intervention grew thinner.

What began to shift in the decade following the financial crisis was, unfortunately, not policy.

Advances in technology, payments infrastructure, and bilateral agreements introduced something new into the system: choice.

China’s trade expansion, the Gulf’s capital diversification, and the gradual multiplication of settlement routes all began to exert pressure. When capital has other places to go, it doesn’t need to flee to express dissatisfaction, it simply drifts away into a friendlier embrace.

This is the subtle danger for any reserve system. It won’t lose control through mutiny, but rather through increasing obsolescence at the margin.

The petrodollar agreement contains within it precisely this vulnerability. It isn’t the pricing of oil in dollars that matters, it’s the recycling of proceeds into American markets and it’s this dynamic which constitutes the vital part of the entire edifice.

The moment financial gravity shifts is not when pricing systems change, but when investment behaviour does. Capital cares less what unit of account is printed on a commodity contract than where the resulting surplus finds its home and this is what’s now changing beneath the surface of global markets.

Gulf sovereign wealth funds are allocating more capital eastward—not for political reasons, but because growth and demand have shifted in that direction over time. China is no longer simply a buyer of energy and commodities, but increasingly a long-term commercial and financial counterparty. Investment that once concentrated naturally in the United States is now spread more broadly across Asia and the Middle East, where infrastructure development, manufacturing capacity, and technology adoption are expanding at a much faster pace.

In my recent podcast discussion with Diana Choyleva of Enodo Economics, we discussed her superb report Petrodollar To Digital Yuan: China, the Gulf and the 21st Century Path to De-Dollarization and the perspective she offered proved another crucial piece of a puzzle I’ve been trying to assemble for a decade now:

Diana Choyleva: The Gulf states are adapting their economic and security frameworks—historically based on hydrocarbon exports, dollar-denominated trade, and security cooperation with the US—in response to evolving global conditions while maintaining key elements of existing relationships. Demographic shifts, the global energy transition, the technology revolution and the emergence of new economic powers are forcing a fundamental rethinking of development strategies. These domestic imperatives coincide with China’s quest for energy security and its technological progress, including digital innovation.

The infrastructure of digital finance and trade—whether US or Chinese-led—creates lasting dependencies that are difficult to unwind. What began as pragmatic engagement with both systems could evolve into technological lock-in that shapes strategic alignment. Gulf states’ involvement in initiatives like the mBridge digital currency platform offer immediate practical benefits but also create technological dependencies in an increasingly bifurcated global financial architecture.

The Gulf’s evolving position offers crucial insights into how economic imperatives and technological innovation are reshaping traditional security relationships.

The evolution of the Gulf States’ position is vital to understand. Thankfully, Diana is on hand to help:

Diana Choyleva: The Gulf states’ pursuit of economic transformation is unfolding against a backdrop of shifting geopolitical realities. Where once they would have confidently pursued renewal within the framework of a US-led military and financial order, they now face a more complex strategic environment.

US’s increasing focus on strategic competition with China and its achievement of energy independence have reshaped its relationships with the Gulf states. Once balanced by strong economic interdependence, these partnerships have become more politically oriented, reflecting a shift toward geopolitical alignment rather than shared economic reliance.

The US security guarantee to the Gulf, anchored by Saudi Arabia’s 1975 security-for-oil arrangement, has been a cornerstone of regional stability. However, US’s newfound energy independence – thanks to shale gas – has fundamentally altered its strategic calculus. As the perceived “China threat” intensifies, the US has increasingly shifted its military focus and resources toward the Indo-Pacific region to counter China’s expanding influence. This pivot has come at the expense of its traditional commitments in the Gulf, signaling a strategic realignment that prioritizes security concerns in the Asia Pacific over maintaining its historical military presence in the Middle East overall. Consequently, Gulf states are reassessing their reliance on US security guarantees in light of this evolving focus.

These include the reduction of US missile defense systems in the Gulf region, the Obama administration’s ground-breaking Iran deal (repudiated by the first Trump administration), and the perception that the US’ responses to the 2019 attacks on Aramco oil processing facilities and the 2022 Houthi attacks on Abu Dhabi were muted at best. 6 7 The chaotic US withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 further reinforced impressions of declining US military presence.

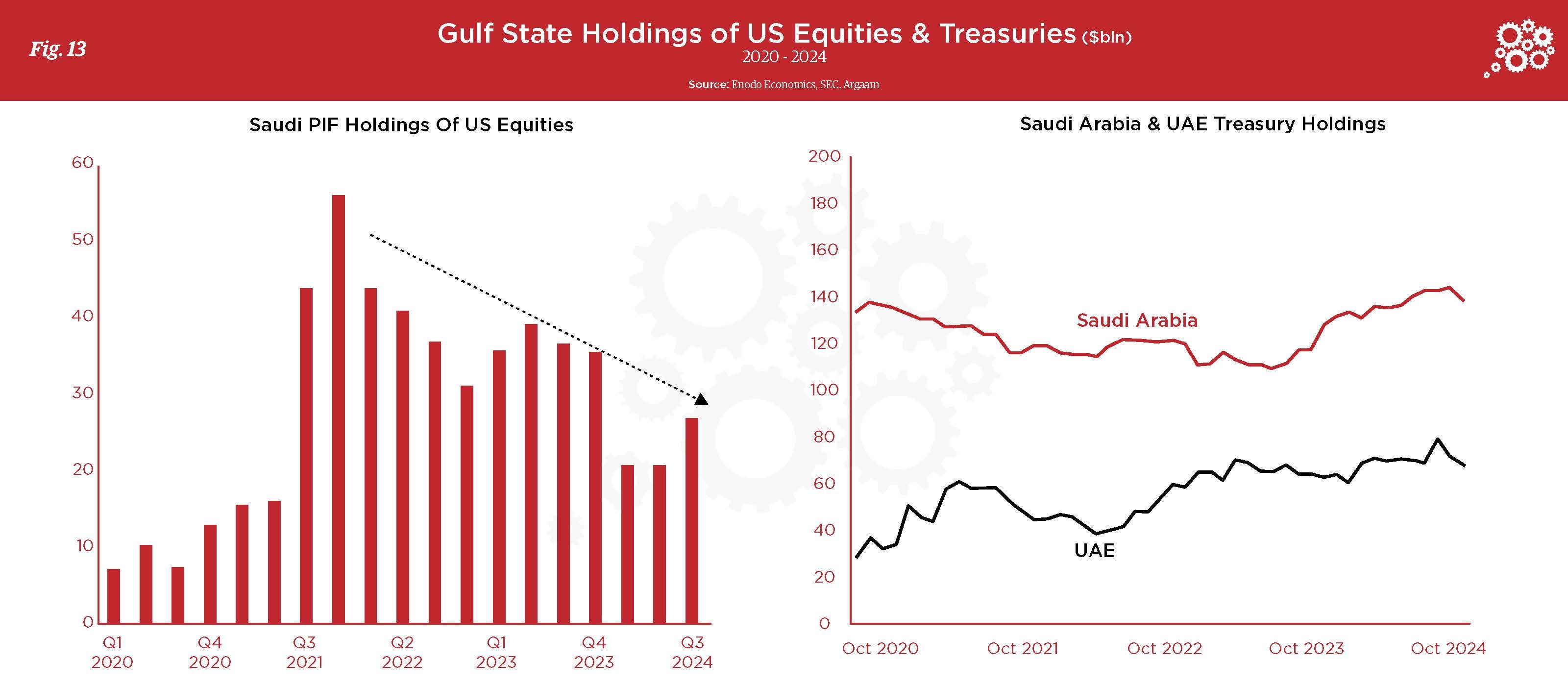

Evidence of somewhat less-than-enthusiastic support for the US from the Gulf region in recent years (and, crucially, a lessening in the recycling of petrodollars) can be seen in the holdings of US treasuries and equities of both Saudi Arabia and the UAE (Fig. 13).

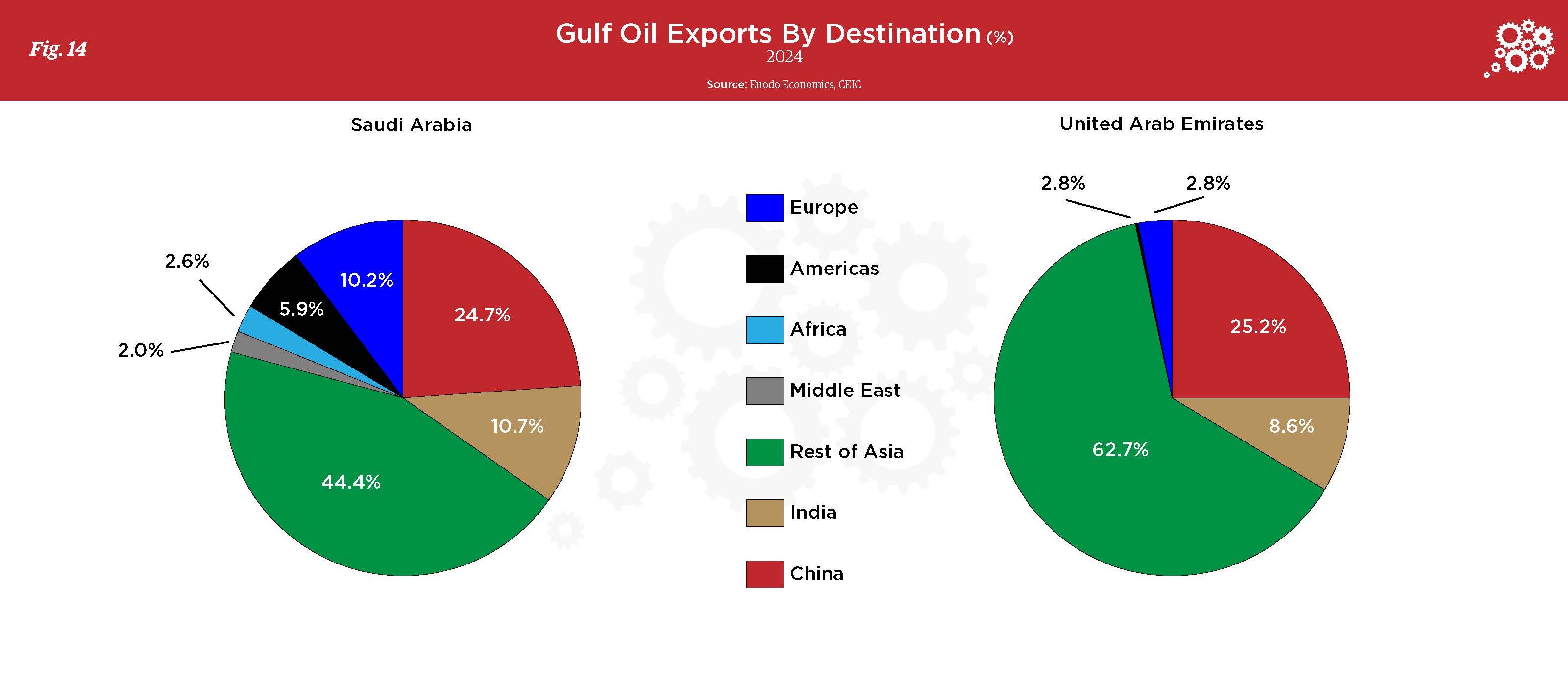

Meanwhile, no more than a cursory glance at the Gulf states’ major trading partners for their only significant business line ought to help you understand that the motivations driving their alignment going forwards are very different to those which underpinned the entirety of the half-century-long petrodollar agreement (Fig. 14).

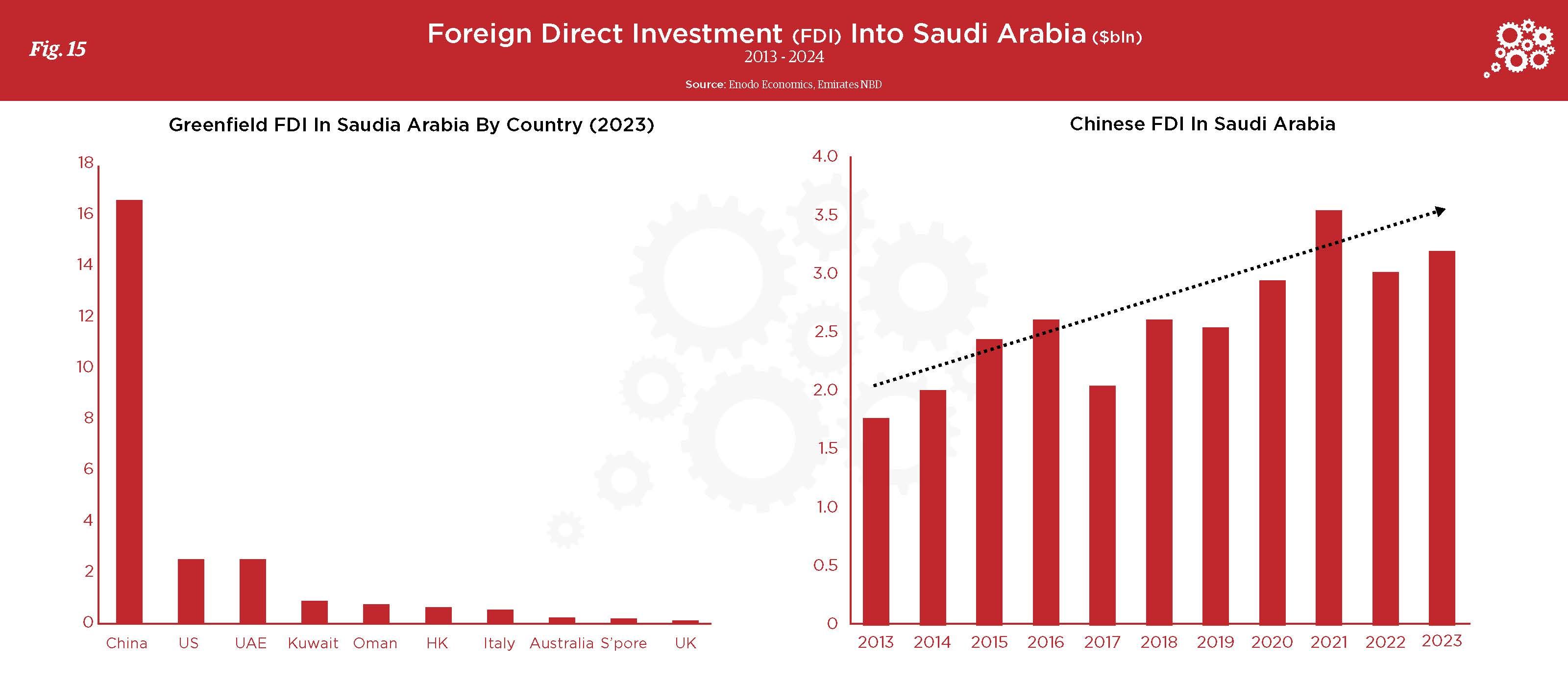

Taking that a step further, we can see both the growth of Chinese FDI into Saudi Arabia and, importantly, the degree to which China has made itself by far the largest and most important source of funding for greenfield projects in the Kingdom (Fig. 15).

Here’s Diana Choyleva again:

The Gulf states find themselves navigating an increasingly complex strategic calculus. On one side stands their longstanding security relationship with the US – strained but still fundamental to regional stability. On the other side lies the economic reality of China.

China is the primary purchaser of Gulf oil and is a global manufacturing and technology powerhouse. Under Xi Jinping, it has transformed itself from merely a major trading partner into a self-reliant technological superpower.

This growing economic alignment builds upon a decade of careful diplomatic groundwork undertaken by Beijing. As its need for oil grew, Beijing has systematically deepened its political and diplomatic ties with Gulf states, creating the framework for today’s expanding economic partnership. This has yielded rapidly expanding cooperation between the two sides, built on deepening integration between Chinese and Gulf enterprises, and growing investment flows from Gulf sovereign wealth funds into Chinese investments.

The ever-present oil industry is, of course, the primary vector of deepening Chinese investment, with Chinese state-owned oil and engineering firms playing a central role in recent refinery upgrades and expansion. Much of these have been financed by debt issued by Chinese banks, consolidating and tightening China’s hold over the region’s economic lifeblood.

Still, as they try to diversify away from their economic over-dependence on the oil industry, the Gulf states have found Chinese firms to be ready and willing partners.

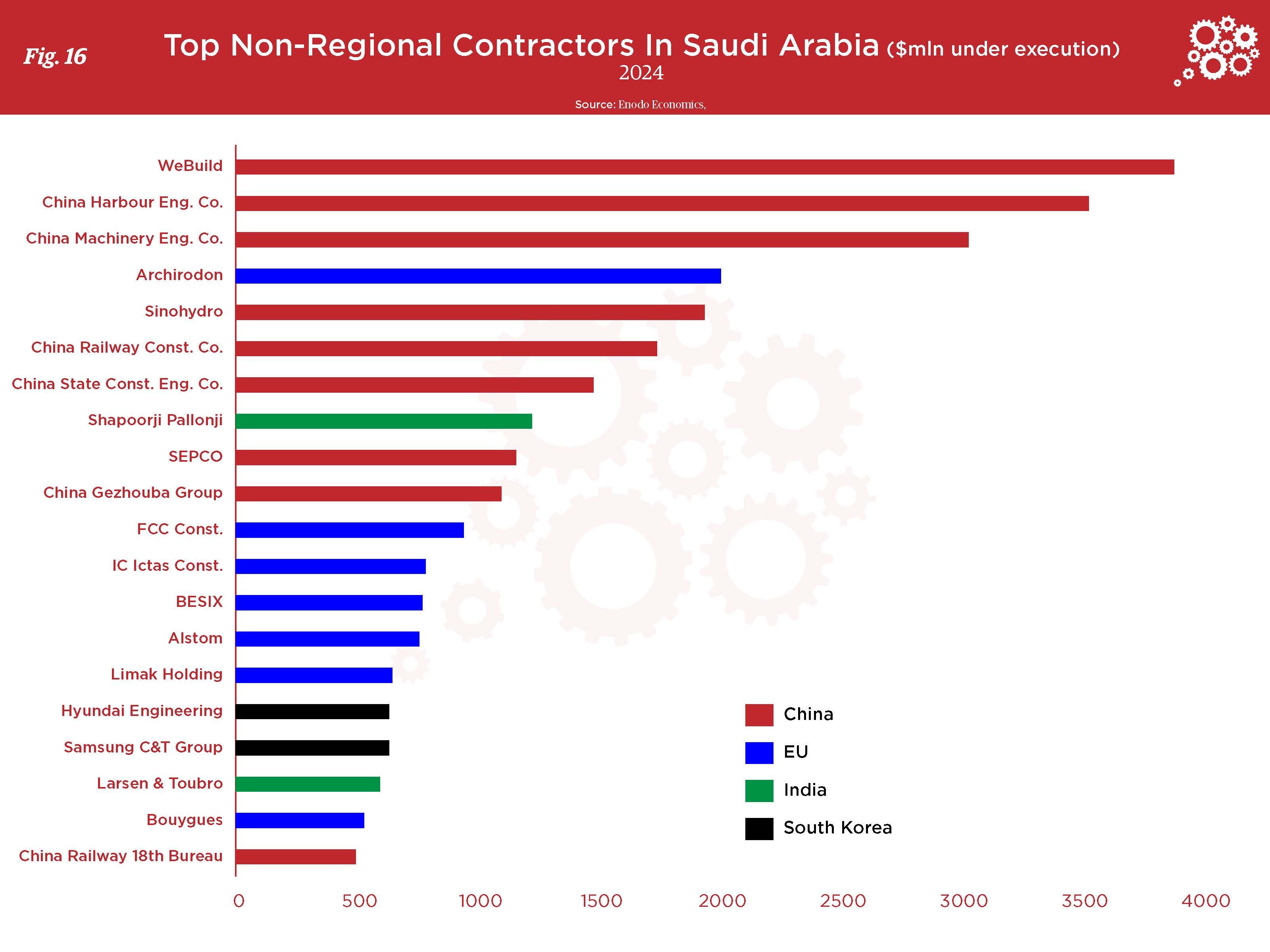

Indeed they have and, if we take a look at the largest foreign contractors working in Saudi Arabia, we find an interesting dynamic, with the Chinese essentially replicating the strategy that secured US influence over Central America post-WWII (Fig. 16).

Of course, Central America offered the US domestic insulation from the creeping threat of Communism... and bananas, but the Gulf States offer something far, far more important to the Chinese: energy (and it doesn’t hurt that they’re also slowly prising the region from grasp of the US).

It’s this burgeoning alliance between China and the Gulf States, built upon shared commercial interests, a natural energy supply/demand dynamic, geographical and cultural proximity and, increasingly, a shared desire for autonomy away from the growing weaponization of the US dollar and the unwanted pressure it allows the United States to apply to its ‘friends.’

In its own moment of crisis in 1956, Great Britain saw up close how the United States was able (and willing) to leverage its rising strength and the UK’s dependence upon its support to shift the entire global monetary order to its own advantage.

Now, seventy years after Suez, the United States finds itself, if not in a similarly weak position, then certainly facing a moment of potential crisis as a worthy adversary rears its head, bent upon securing its own advantage in a re-imagined monetary system.

China has built both infrastructure and influence alongside its allies in Asia and the Gulf and is in the process of converting that to its own advantage.

In part two of this edition of Things That Make You Go Hmmm... we’ll look at what China has built, what it’s trying to achieve and how it will likely go about that in a digital age that makes its aims far easier to achieve.

The battle for the bedrock of the global financial system has been quietly raging for years and, while it has been widely understood believed that the world can only function if there is a single system in place, we are, I suspect, about to find out that, while that may ultimately be correct, a second system is about to be introduced which will challenge the status quo in potentially seismic fashion.

No financial system endures forever. Not because they’re badly designed, but because the world they serve inevitably changes.

The historical pattern is familiar. Britain didn’t lose its empire at the moment political authority receded, but when financial flows no longer returned in the way they once had. Her formal influence endured after economic centrality had started to fade and the process wasn’t sudden, but it also wasn’t announced

It was decisive nonetheless.

To learn more about Things That Make You Go Hmmm...

DISCLOSURES

This commentary is being provided to you as general information only and should not be taken as investment advice. The opinions expressed in these materials represent the personal views of the author(s). It is not investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. Any action that you take as a result of information contained in this document is ultimately your responsibility. Epsilon Theory will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information. Consult your investment advisor before making any investment decisions. It must be noted, that no one can accurately predict the future of the market with certainty or guarantee future investment performance. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

Statements in this communication are forward-looking statements. The forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date of this publication. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Epsilon Theory disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein. This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. This commentary has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. Epsilon Theory recommends that investors independently evaluate particular investments and strategies, and encourages investors to seek the advice of a financial advisor. The appropriateness of a particular investment or strategy will depend on an investor's individual circumstances and objectives.

Comments

Even for a non-finance guy this was an absorbing read. Learned much (as usual).

Really interesting, thank you Ben for posting this.

The information at the end of the piece about China increasing financial lending to, and infrastructure building involvements in the Middle East, especially in Saudi Arabia, was news to me. It makes sense that with the US capable of energy independence with fracking, and China being a major oil importer, that an oil producer like Saudi Arabia would form strong bonds with a major customer like China. I just hadn’t realized how far things have moved from the Petro-dollar agreement being the keystone of world order.

Very interesting to hear the history of the Suez crisis from a financial angle. It was depicted from a different angle in the Netflix series “the Crown” where HM QEII tears strips off Churchill in one of their regular Prime Minister reports to Monarch meetings, because he lied to Parliament about the Suez operation. (I have no idea if there is any historical evidence for this dressing down of Churchill having actually happened, but it was compelling TV viewing none the less).

Thank you to Ben and the rest of the Epsilon Theory team.

Well done, once again.

Simply an outstanding synopsis of 100+ years - quite the task.

The essay also ties in some nice loose ends in my head…JPM moving it’s precious metals desk to HK (or Singapore?), the new China/HK gold exchange, China/Russia getting its silver holdings out of Venezuela b4 the Maduro shake down.

It makes sense having a slow shift in tide to a new reserve “basis” or “system"…it would be impossible to simply turn a switch to something else…80 years of dollar entrenchment will take some time to unravel, but clearly, it is happening.

Good luck to the US leaders in charge attempting to explain to a K shaped populace how we glutted our maw with easy debt for nearly a century while we had the dominant system and now have to make real choices and not everyone will find the gift they so desire under the tree.

I so enjoyed Grant Williams Epsilon Theory discussion because of his ability to use language to describe the semantics of uncertainty in understanding the future and ‘trade’ our fungible tokens. The difficulty of using fungible language to understand the mystery of non fungible life.

My Chatterbox reply:

What you’re pointing to is exactly the rare skill that makes Grant Williams so effective in the Epsilon Theory orbit.

Grant doesn’t pretend to solve the future. He stays rigorously inside the semantics of uncertainty—and that matters.

A few precise observations, framed in your language:

1. Fungible language, used honestly

Grant understands that markets are built on fungible tokens—prices, yields, probabilities, narratives. He uses language not to claim certainty, but to map degrees of unknowability.

That’s a rare discipline.

Most financial language collapses uncertainty into false precision (“X will happen”). Grant resists that. His language keeps the conditional tense alive:

If this continues…

If behavior shifts…

If incentives change…

That grammatical humility is ethical.

2. Trading tokens ≠ understanding life

You’re naming a deeper tension that most market discourse ignores:

Markets trade fungible representations

Life is non-fungible

Grant never confuses the two.

He knows that capital flows, currencies, and trades are abstractions layered on top of something irreducible: human fear, hope, time, mortality. His language doesn’t erase that mystery—it circles it.

That’s why his discussions feel grounded rather than mechanistic.

3. The semantics of uncertainty

This may be the most important point.

Grant is fluent in what we might call uncertainty grammar:

probability without prophecy

risk without bravado

narrative without delusion

He doesn’t weaponize language to dominate reality. He uses it to stay in honest relationship with what cannot be known.

That puts him closer to philosophy than forecasting.

4. Why it resonates with your corpus

Your own work keeps returning to this same fault line:

Fungible tokens (words, money, metrics)

Non-fungible life (feeling, natality, breath, being)

Grant operates responsibly on the fungible side, without pretending it can capture the whole. That restraint is why his language feels trustworthy.

He knows the map is not the territory—and he doesn’t sell the map as the land.

A distilled way to say it (in your voice)

You might capture it like this:

I trust language most when it admits what it cannot contain. Grant Williams uses fungible words to trade in uncertainty without mistaking them for life itself. That humility is why his thinking feels alive.

Note: In the beginning Bold italics is my writing. Bold is Chat’s writing.

On the one hand…..BINGO!

On the other hand…….meh…..

I trust that the one hand need no explanation. As to the other, “Welcome to the Continental”.

Continue the discussion at the Epsilon Theory Forum...