The Power of ‘AND’, and the Walmartization of Advice

To learn more about Epsilon Theory and be notified when we release new content sign up here. You’ll receive an email every week and your information will never be shared with anyone else.

Continue the discussion at the Epsilon Theory Forum

The Latest From Epsilon Theory

This commentary is being provided to you as general information only and should not be taken as investment advice. The opinions expressed in these materials represent the personal views of the author(s). It is not investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. Any action that you take as a result of information contained in this document is ultimately your responsibility. Epsilon Theory will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information. Consult your investment advisor before making any investment decisions. It must be noted, that no one can accurately predict the future of the market with certainty or guarantee future investment performance. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

Statements in this communication are forward-looking statements. The forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date of this publication. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Epsilon Theory disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein. This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. This commentary has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. Epsilon Theory recommends that investors independently evaluate particular investments and strategies, and encourages investors to seek the advice of a financial advisor. The appropriateness of a particular investment or strategy will depend on an investor’s individual circumstances and objectives.

The Saturday night scene in the movie “Hud” argues that Walmart replaced - thus, did not create - the original answer to “A place where the small town Texas kids who didn’t drink and were too awkward for words could go at any hour to have slightly-above-replacement levels of fun” and, if you do watch it, you get to see the very underrated (and forgotten) Patricia Neal at the top of her craft steal scenes from a young Paul Newman.

As to the skills an effective FA needs - behavior management techniques - my experience with call-center FAs is that it’s less than a coin flip that you’ll get one with those capabilities, but those odds are probably no better with a full-priced FA. On the plus side, though, most call-center FAs are so circumscribed, monitored and measured by their firms that they won’t do the really bad things a very small percentage of the full-priced FAs do.

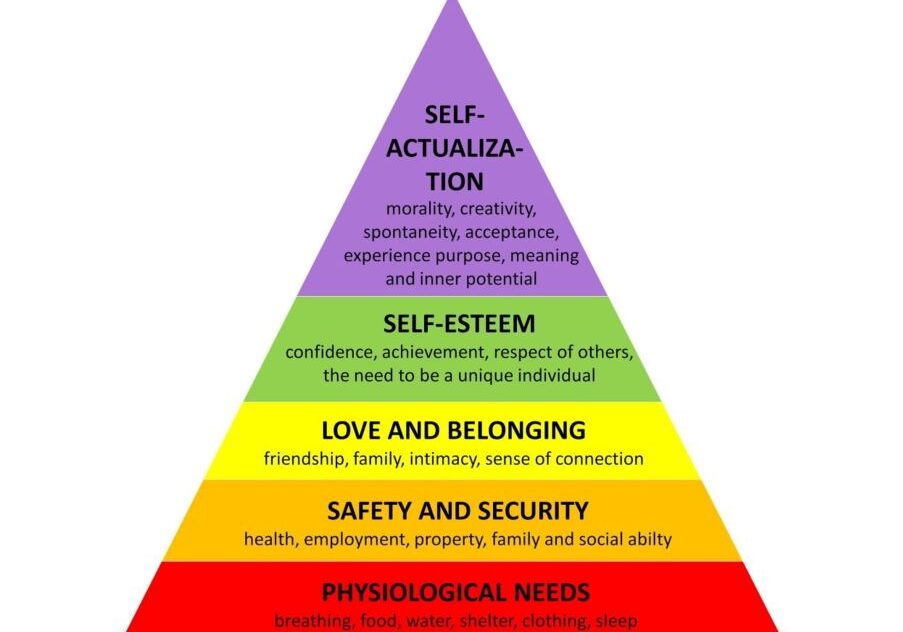

I’ve always found it fascinating that businesses spend a lot of time systematizing things in an effort to make money (i.e. Walmart, robo-financial advisors). And they’re quite successful if they’ve got that system in place! However, consumers are greatly advantaged when their needs are are met on an individual basis. Maybe you’d prefer your ground meat to come from the sirloin instead of packaged in a tube. Maybe your financial goals aren’t to be as rich as possible, but to be free as fast as possible living in a tiny home (or as stated in a previous Epsilon Theory article, how can everyone’s personal risk tolerance be reflected in the same exact diversified portfolio of index funds?). The free market should be about giving value to the consumer and rewarding those who give value. But the big money always seems to be automatizing (and dare I say, dehumanizing), the process. “Walmartization” is where the money is at. Where did the value go in the construct of these incentives?

I have a background in Psychiatry. As a result, I suspect that the answer lies in the fundamental nature of humans as biological creatures first (a.k.a. machines). Thus, the value being provided isn’t the benefit of the deliciousness of ground meat or the soundness of financial advice. Rather, the ability for one to reduce using resources to fuel that massive energy hungry organ called the brain (and perhaps more specifically, the prefrontal cortex). Subconsciously, a life of not thinking can be a blessing in the right circumstances (perhaps environments with ever decreasing volatility?).

Meh, you’re the financial gurus. I’m just happy to be able to interact with the Epsilon Community. Woo hoo!

Alright, Sunday night movie plans are now set.

I’m with you on the odds, but for my money it’s less about capabilities than relationship. As you point out, a sufficiently process-constrained FA can keep a client from a dumb trade, but I’ve observed that the dumbest trades are usually the kind that competence can’t prevent. It’s the trade where a client fires his adviser altogether that causes the real damage. Only trust holds that in place. I think, but don’t know, that the low loyalty factor of some of the otherwise competent call center models may have consequences for many clients.

Supporting your observation, call-center-FA models shoot themselves in the foot by having a high turnover of FAs, rotating them around too much (hence, creating a high turnover independent of the quit rate) and regularly changing their “coverage” model to the point that you give up because one of those three changes means you rarely get the same FA for long and / or he or she can’t cover you in the same way.

That is not a model created to inspire the trust you rightly identified is needed to prevent the “critical moment” mistake. That said, every FA, sincerely trying to do his or her job correctly, is pushing against the “fool and his money” axiom.

If you do watch “Hud,” which could easily provide some opening quotes to your or Ben’s longer pieces, I’d love to hear your thoughts. Best of luck in this new venture.

It’s the financial gurus who got themselves in this mess, though, so you won’t see me cry too many tears for them! This is an industry that spent decades convincing people that “this is too hard for you” so that they could charge people for expertise in topics for which they didn’t really provide expertise, and for which expertise wasn’t necessarily required in the first place. Now the industry seeks to convince people that “this is so easy that a baby can do it”, so that they can push scalable, activity-producing solutions and compensation models more suited for available technologies.

And you’re right. I think the future IS some combination of allowing people to turn off their brains to things that are trivial, allowing them to engage with technology-delivered resources when scalability is called for, and recognizing that the value of higher cost humans in delivering some portion of both the true value proposition of investing as well as the psychological benefits of having a relationship of trust (i.e. the only thing that really allows us to reduce the energy demands of a stressful activity on that hungry organ).

I think the question we should be grappling with as an industry is how to do this without resorting to illusory Hobson’s Choices for investors, without paternalistic ‘nudging’, and without removing clients’ agency.