To receive a free full-text email of The Zeitgeist whenever we publish to the website, please sign up here. You’ll get two or three of these emails every week, and your email will not be shared with anyone. Ever.

One of the foundational ideas of the Zeitgeist is that measuring linguistic similarity is a powerful way to observe what we are being told matters by those who publish most of the words we read in a given day.

It should be intuitive that the source of that similarity is sometimes reducible to topics. If a single event is dominating headlines, then language that describes that event is going to cause measures of similarity to rise. This is useful, but not especially interesting. You don’t need us to tell you when a topic is dominating headlines.

That is why when we write about Narrative in terms of our measures of linguistic similarity we tend to either control for topic (i.e. we look at measures within topical sub-sets of news) or focus on the evolution of topic behaviors over long periods of time. We think these are powerful ways to observe when a story and its associated vocabulary have become Common Knowledge.

Sometimes, however, concentrating on a single topic can make it easy to miss the connections of a narrative across multiple disciplines. In other words, there is practically no information (by which we mean something that would make you change your mind about something) in the observation that people are talking about the same things. There is some information in the observation that they are using the same language patterns to talk about it, since that implies some measure of other-regarding behavior. But there is a lot of information in the observation that multiple otherwise unconnected disciplines or lenses for looking at the world are applying the same language to those different angles of a connected problem.

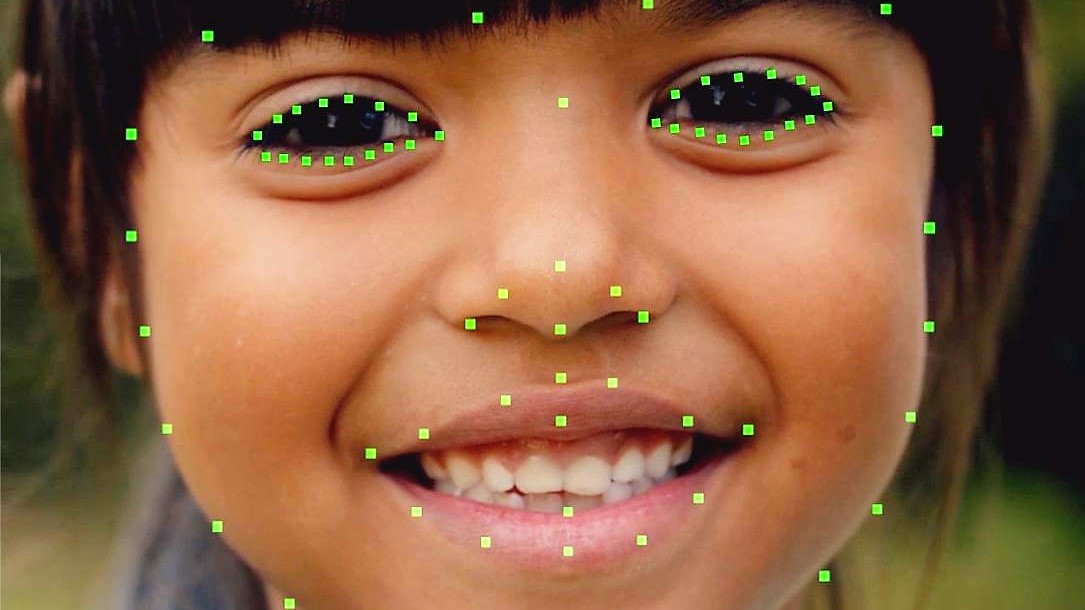

You can think of it as the linguistic equivalent of the discovery of the fossils of a handsome specimen like that lystrosaurus pictured above on the Indian subcontinent, China, Africa and Antarctica, a discovery that permitted us to draw new connections between an entire range of scientific and cultural topics that went far beyond a pig-like creature from the early Triassic. Like, say, plate tectonics, geology, evolution, and cross-cultural similarities in mythologies and legends.

But just in case the analogy feels like I’ve been playing a bit too much quarantine science teacher (guilty as charged), let me tell you in more practical terms what I’m talking about.

Yesterday I got three emails.

The first was from a long-time friend, a specialist in technology and VC law, who sent me a link to this piece from the Wall Street Journal.

If Inflation Is Coming, the Market Isn’t Ready

The second was an email from a CIO at a Top-5 university endowment who circulates a daily list of what he is reading to friends and colleagues. This one is behind a research paywall, but you get the topical gist from the headline even if you don’t subscribe.

The State Of The Stock/Bond Relationship

The third was an article that topped the Zeitgeist last week, but didn’t make the cut to produce a full-blown article from us (at the time, anyway).

Why It’s Time to Rethink Bonds

If you don’t subscribe to the WSJ, all three of those links may be behind a paywall for you, but it doesn’t matter. I don’t think any of the articles is particularly informative, or at least I don’t think that any of them provides any new or novel insight. What is fascinating to me is that within a week, a professional market research shop, a personal finance writer and a financial markets journalist all took on the question of “the role of bonds.” What is fascinating to me is that within that same week, a bright private markets specialist (but public markets layperson), one of the ten or so most important asset owner CIOs in the US and an NLP algorithm all told me that “the role of bonds” is something that was on their mind and the minds of others.

We aren’t predicting. We are observing.

I can’t tell you how to gaze through the fog of a deflationary shock to predict what the Fed’s unprecedented intervention will mean in the medium- and long-run for prices. I can’t tell you if and when the macro regime will become one in which bonds cease to diversify stock exposures like they have for the past 35+ years. I can’t tell you whether financial advisors and individuals change the way they think about the role of the bonds in their portfolios.

But I can observe that enough people are thinking about it – and enough people know that other people are thinking about it – that common knowledge is forming around the question. If I can be permitted one pretty uncontroversial prediction, it is that the narrative, NOT the reality of inflation or correlation matrices in the real world, will be the force that causes investors to change their behaviors and portfolios.

We’ve been ringing the bell for asset owners and advisers to figure out how our industrialized investment ecosystem and crystallized processes may need to be adjusted to handle change in the narratives of inflation and the stock/bond relationship for a couple years now.

We rang the bell here:

We rang the bell here:

And we rang the bell here:

And while the uncertainty and opportunities of COVID-19 and politics may be (appropriately) front of mind for investors, while the reality of inflation may feel miles away, we are ringing that bell again.

Rusty, if you look at the ICI Statistics you’ll find that combined ETF & Mutual Fund flows out of fixed income product were -$274 billion in March. The next previous months of outflows was -$62 billion in Q4 2018. Normal monthly flows are positive and an eyeball average puts them in the +$40 billion range.

The aggressive Fed intervention in the repo market in mid-March tells me that a rapid backup in spreads was blowing up levered ETF carry trade. the Fed in essence told levered speculators that they were free to go back to their games. It’s interesting that the Fed is now using a “custom index” to guide their corporate bond purchases. I wonder what the correlation is to the aggregate hedge fund bond book.

If you look at column 3 of the ICI weekly report, you’ll see that combined flows into domestic equity ETFs and mutual funds have been solidly negative since January of 2018. Inflows in April of this year were +$2.7 billion, insignificant from an index POV. THIS MARKET MOVE IS NOT RETAIL DRIVEN. What is clear is that gaps on open are driven by the futures market.

Levered speculators are setting direction for both the stock and bond markets. In my view the question to ask is “What is the role in the portfolio of publicly traded securities going forward?”

A link to the ICI data: https://www.ici.org/info/combined_flows_data_2020.xls

A good picture of retail flows can be found on Fidelity’s website:

https://eresearch.fidelity.com/eresearch/gotoBL/fidelityTopOrders.jhtml

Most of what they’re trading is irrelevant from an index/market direction POV.

Sandy - The retail mania is bypassing ETFs. It’s direct stock trading, free and in fractional shares being offered by the major retail houses. If you have access to Jim Bianco’s work he has done great analysis on this stuff. ETFs are yesterday’s game in retail land.

There have been several articles recently pointing out the increased prices at the grocery store. It’s only a matter of time before people realize they’re paying more for food. I have been thinking that what we will see is cost-push inflation and the food sector would be the first to see it. Feeding (no pun intended) this trend will be the push for different farming practices that inevitably increase costs. For now, it appears to be near-term supply shocks (covid logistics) and food hoarding (rice buying in Asian countries), but if it carries on much longer, people will begin to take notice and it snowballs.

I’m not really commenting on anything that may be driving present market volatility, Sandy. This is an observation on narratives that I think work in a much longer horizon. Leaving that to the side, as Rafa points out (I think correctly), I think there is mania behavior in individual securities AND I think that broader market moves tend to be driven by institutional futures flows. Both can be true, and I think that both are.

Our concern about the role of public markets being treated as utilities probably connects with your question, which I think is fair, but that makes an almost diametrically opposed point. To wit, institutions aren’t going to stop owning equities because they simply cannot. Yet they are actively considering whether they ought to own bonds. That’s the narrative that’s showing signs of life, I think.

Not just Institutions…….a Mauldin publication I receive, ETF20/20 by Jared Dillian had this to say in the context of hedging a possible leg down next in the Stock market :

“Treasury bonds are mostly useless at this point. The Fed might implement Yield Control Curve but it is unlikely to do it at maturities past five years”

&

“Looks like things are going to be bumpy for a while. In the past, we held Treasury Bonds as a hedge-but that no longer makes any sense”

Two things have been obvious to me for a couple of months. First, experienced price inflation will be going up significantly. Second, that increased price inflation won’t make it into the inflation measures.

Everyone’s buying patterns shifted in very consistent ways beginning in March of this year. The items which are suddenly in hot demand (less-perishable food, prepping gear, firearms, gardening supplies, hobby supplies) can still be found, but at a high premium compared to 3 months ago. There was a second wave of price changes when the CARES act payments rolled out; TVs, computers, video game consoles, and other semi-pricey consumer electronics suddenly became a lot more wanted.

Pre-March I spent about 24% of our monthly household budget on food. There was a outlier surge in March when I stocked up, but now just eating from week to week is consuming 31% of our budget on average, with no change in income over the time period (thankfully!).

The mechanism that Ben wrote about in “Misfortune vs Carelessness” will be used to prevent these significantly higher experienced costs from showing up in official inflation reports for quite some time, though. I can see 5 years down the line the usual suspects trotting out something along the lines of “oh gosh, our inflation statistics didn’t capture this new inflation when it started. It wasn’t our fault, it was the hedonic quality adjustments and the sudden shift in purchase patterns. Nobody could have predicted that shift. Our models seemed to be working fine. Used car prices and airfare were so cheap that the deflationary measures swamped the inflation in things people were actually buying.”

I did a similar review of my own finances - constrained to good data I had from Amazon orders - and found that it went a good bit beyond even some of those categories. By the same token, however, I do think we have to recognize that fuel, leisure and in some cases housing have been reduced for some Americans. I don’t think it invalidates the point at all AND I think you’re right that the strategies Ben describes will continue. AND I also think that the narrative of inflation and pointlessness of bonds can happen at the institutional level without any change in real-world inflation, reported or otherwise.

Good observation! Yes. it is broader than institutions, I just think those are where the rubber meets the road on asset prices.

That’s why I included the link to Fidelity’s retail flows: the stocks they are trading are generally u important from an index POV. Institutions may be forced to continue to own publicly traded equities but market direction is driven by the futures markets.