The circular process of issuing new shares to employees and then buying those shares back with company money - MY money as a shareholder - is called 'sterilization'.

Sterilization has been around forever, and to a limited degree it's fine. Yes, management teams should get some reasonable level of stock-based compensation. Yes, it may make sense to use some of my cash to sterilize those shares and keep the share count from expanding. But don't tell me that the sterilization of newly issued shares is anything other than a direct compensation expense that I am paying for with MY money. Don't tell me that the sterilization of newly issued shares is somehow a "return" of cash to ME, because it's just not. The sterilization of newly issued shares is a direct transfer of my money to YOU, the recipient of those newly issued shares. Nothing more, nothing less.

I believe that there has been a sea change in markets over the past ten years in the size and scope of these sterilizing stock buybacks.

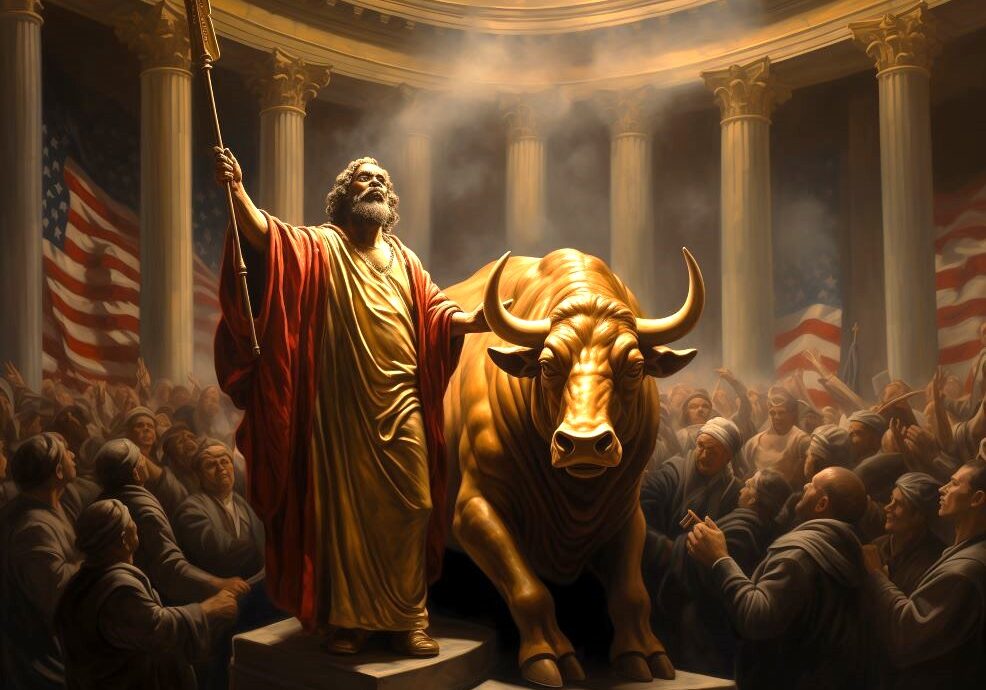

I believe that there has been a truly astronomical transfer of wealth - well more than a trillion dollars - over the past ten years from shareholders of publicly traded companies to managers of publicly traded companies. Not founders, not entrepreneurs, not risk-takers ... managers.

I believe that this sea change has been driven by the intentional trumpeting of three narratives by management teams, boards of directors and their rah-rah Wall Street/CNBC accomplices:

- "Our Interests Are Aligned" to justify larger and larger amounts of stock-based comp,

- "Non-GAAP is the Best Way to Understand This Company's Fundamentals" to justify downplaying stock-based comp and share dilution as a crucial issue for investors, and

- "We're Returning Cash to Shareholders" to justify the sterilization of that stock-based comp with stock buybacks.

Here's how it works:

BOOM Ben --Fantastic work! Reminds me of the work you did on the AMA.

I would change only one word:

Step 4: Wall Street/CNBC Renfields trumpet the sterilizing stock buyback as “returning cash to shareholders”, encouraging shareholders to not only ignore the transfer of their money to management, but to embrace it.

Bravo! Adding Apple as an example of non-mendacity forces the reader to confront the cartoon version rather than hiding behind the uncritical popularity of the tool. I also think that the closing argument that even greater mendacity has been rewarded at a negative cost of capital seals the deal. I am sending this note to outside advisors of our endowment as required reading for their analysts who pick individual stocks on our behalf.

Thanks, Patrick! I’ll get you a PDF version of the note later today for easier distribution.

The fact that companies automatically pay the IRS in cash upon RSU vesting is an interesting one and not something I had realized. It seems almost as if these companies are taking a short position in their own stock, because on the grant date they are effectively making a promise to buy back a fixed percentage (say 30%) on the vesting date. The higher the stock price goes, the bigger the liability becomes.

My “favorite” is the “we are authorizing a buyback to offset dilution” canned justification… while at the same time reporting Non-GAAP to because “stock compensation is a non-cash figure”

Long the narrative, short the fact!

I asked my father (32 yrs as an advisor) what percentage of Meta’s FCF was used on buybacks and how much said buybacks shrank the float. When I gave him the actual numbers his jaw dropped. Normal investors have no idea how much they’re being played by some of these companies.

Fantastic observation that I had not considered.

Most institutional investors, too!

Great Note! None of the companies in this note have a high gross leverage or net leverage ratio but many companies do from issuing mountains of debt to buy back shares during the post GFC financial repression era. Not only taking shareholder money via sterilization but leaving them with a levered-up more vulnerable investment too. Alas the institutional bond investors fell over themselves to buy these deals because they were “10 bps cheap to secondaries” .