This is cedar rust.

It is the effect of the fungus gymnosporangium juniperi-virginianae on an apple tree leaf in my orchard. This fungus has infected a particularly lovely Yarlington Mill tree that would otherwise make a rich English-style single-varietal cider.

I can slow cedar rust down.

I can spray the tree with copper or sulfur, and it’ll kill some spores. I can spray the tree with something ‘organic’, and it’ll make the spores smell like whatever ‘organic’ goop I sprayed them with. Neither strategy will stop them. They’re in the air, on the bark and on the ground. Any leaf on this tree that has been infected with cedar rust this season will eventually curl, yellow and die. Any new leaf on the same branch will still almost certainly become infected. Even on new growth on a different branch, the prognosis isn’t very good. I’ll lose every leaf on this tree this season before its time.

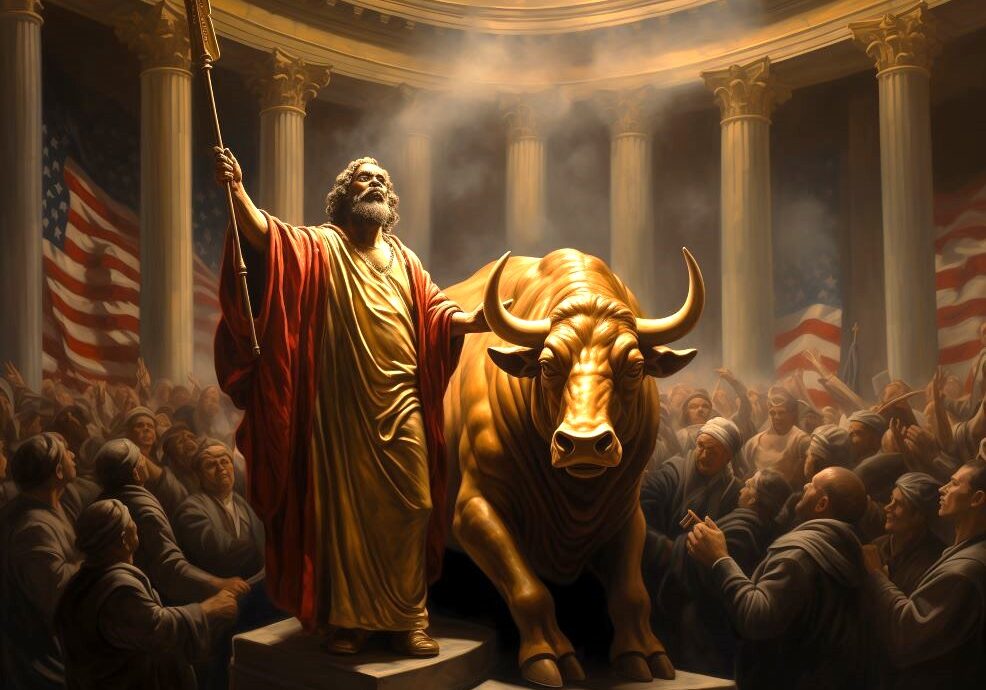

Flight 93 Elections, very well put sadly!

Re: the apple trees. My Grandfather came over from Poland @1905, bought 7 acres in N, Greenwich (Riversville Rd,). He planted a variety of Macs. Summers we would prune, trim, spray (alar) and burn. The leaves above look all too familiar. He would make Jack and my Grandmother’s apple pies…good memories. But while we worked he talked and I listened. Common knowledge. He made me listen. It’s a different time.

Joseph - thank you for this story. Loved to hear this.

Thanks, not-on-an-apple-tree Rusty! Your analogy here is powerful for anyone with a connection to the land and trees. On a different note: I do think knowing one’s family history is helpful, if possible. My (Scots-Northern) Irish patrilineal ancestors also arrived mid 18th century in Philadelphia most likely moved a bit west into frontier Pennsylvania. After fighting in the Pennsylvania Militia and Continental Army, they moved to NE Kentucky, given land to help protect the county from the natives. By 1826 they were in MO, and by 1904, my great grandfather moved to Idaho to plant potatoes. Living examples of your story; however, they seem to have been very devout Presbyterians for a long time as well as farmers, ministers and teachers. For example, my two great aunts earned college degrees in the 1880s and served in Japan as missionaries from about 1896 to 1938, so there were a significant minority of devout upon which your referenced myth was built. I do not argue at all with your basic narrative. I am not religiously devout at this point in my life, but their honest example of faith lived continues to encourage me to take the risk in doing the right thing.

Thanks, Chris! True in my case, too, as it happens. Methodist ministers and circuit riders, although history has proven neither to be a perfect panacea for drunkenness and debauchery.

“Civilization emerges. Conservatism follows when people conclude that they’d like to keep the things they’ve found.” Simply put. Profoundly true. I think this is my favorite Rusty note yet, and there have been many great ones. Thanks.

Hi Rusty,

Do you have any links to references on cedar rust? I planted nine apple trees in my backyard over the last 2 years, and they’ve gotten cedar rust each year.

I think I’ve identified two eastern red cedars on my property that I will take out this fall, but since the spores can travel up to a mile, I think I still need chemical protection. I tried using daconil this past spring/summer, but it didn’t help and I’ve since discovered daconil is not indicated for apple trees.

I’m planning to use neem oil before winter and them spectracide’s immunox every 10 days starting next spring. The sources I found don’t recommend copper.

I really appreciate this post because it helped me discover/understand what was/is going on with my apple trees. Thanks so much!