License to Kill Gophers

To learn more about Epsilon Theory and be notified when we release new content sign up here. You’ll receive an email every week and your information will never be shared with anyone else.

Continue the discussion at the Epsilon Theory Forum

The Latest From Epsilon Theory

This commentary is being provided to you as general information only and should not be taken as investment advice. The opinions expressed in these materials represent the personal views of the author(s). It is not investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. Any action that you take as a result of information contained in this document is ultimately your responsibility. Epsilon Theory will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information. Consult your investment advisor before making any investment decisions. It must be noted, that no one can accurately predict the future of the market with certainty or guarantee future investment performance. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

Statements in this communication are forward-looking statements. The forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date of this publication. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Epsilon Theory disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein. This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. This commentary has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. Epsilon Theory recommends that investors independently evaluate particular investments and strategies, and encourages investors to seek the advice of a financial advisor. The appropriateness of a particular investment or strategy will depend on an investor’s individual circumstances and objectives.

Caddyshack and Happy Gilmore - The Truth and Nothing but the Truth!

And, in the end, the gopher survived. What does that suggest for the future? Gophers, gophers and more gophers all the way down.

Gophers can’t be killed.

Even at the height of the British empire (ie pre-1850,) financial crises that shook the core of the system occurred at regular intervals.

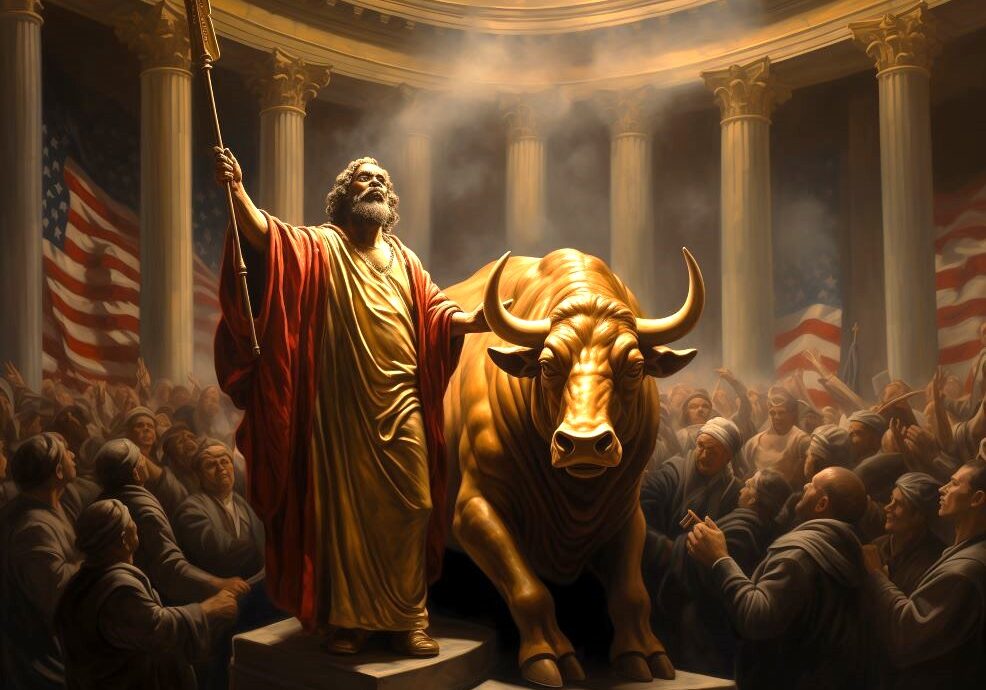

Asset inflation simply can’t be allowed to go on forever. The more it continues, the more unproductive people and processes are paid to be unproductive. The top elites don’t want such a world. They profit from being more prepared than the rest of us for both asset inflation and deflation. Asset deflation and the economic pain that goes with it are allowed to occur once a target of blame, that doesn’t implicate the core world system, is firmly in place.

How firmly is the common narrative associating Trump and the trade war with a bust? That’s how close we are to such a bust.