Once when Hyakujo delivered some Zen lectures an old man attended them, unseen by the monks. At the end of each talk when the monks left so did he. But one day he remained after they had gone, and Hyakujo asked him: `Who are you?’

The old man replied: `I am not a human being, but I was a human being when the Kashapa Buddha preached in this world. I was a Zen master and lived on this mountain. At that time one of my students asked me whether the enlightened man is subject to the law of causation. I answered him: “The enlightened man is not subject to the law of causation.” For this answer evidencing a clinging to absoluteness I became a fox for five hundred rebirths, and I am still a fox. Will you save me from this condition with your Zen words and let me get out of a fox’s body? Now may I ask you: Is the enlightened man subject to the law of causation?’

Hyakujo said: `The enlightened man is one with the law of causation.’

At the words of Hyakujo the old man was enlightened. `I am emancipated,’ he said, paying homage with a deep bow. `I am no more a fox, but I have to leave my body in my dwelling place behind this mountain. Please perform my funeral as a monk.’ Then he disappeared.

– Excerpt from the koan Hyakujo’s Fox

In Zen, a koan is a story or dialogue designed to trigger and test understanding. It’s a fascinating literary form. Incredibly dense. Often, koans convey multiple layers of meaning in less than a hundred words. Sometimes just a few sentences.

The koan Hyakujo’s Fox, sometimes called the Wild Fox Koan, is of particular interest to me because it touches on many of the themes near and dear to us here at Epsilon Theory. Here a monk transforms himself into a fox by “clinging to absoluteness.” While this is absurd on its face, it’s really just a fancy way of arguing that perception is reality.

You are what you eat, the saying goes. More importantly: you are what you think.

Recently, a friend and I were texting about the meaning of life. (what? you and your friends don’t text regularly about the meaning of life?) My friend wrote that in the end, all you can really do is carry your cross to the finish line. I quite like this. It cuts right to the heart of the issue. There are no Answers. There is only Process. I did suggest adding an inscrutable Zen twist, however. My version:

In the end, all you can really do is carry your cross to the finish line. Except there is no finish line, there is no cross, and there is no you.

People sometimes ask me, if all the world is Narrative and Meme, then how can we tell what’s real?

As far as social reality is concerned, it’s about as real as any game or theatre production. There’s the White Collar Corporate Power Game, for example. There’s Partisan Political Theatre. There’s the Social Status Game. If you prefer more high-brow forms of entertainment, you can indulge in Religious Theatre and Intellectual Theatre (I have a soft spot for the latter). But let’s not kid ourselves. It’s theatre and games, all the way down.

This shouldn’t come as news to anyone. Heck, it’s been right there in the Bible for over a thousand years. That bit about the camel passing through the eye of the needle easier than the rich man making it to the Kingdom of Heaven? That’s Jesus teaching that wealth and status are not inherently meaningful or worthwhile. Accumulating wealth and power are just games we play.

A while back, I wrote a note about this manufactured nature of social realities. I wrote then that it was a Clear Eyes note. Well. This is the Full Hearts sequel.

You see, I’m pretty confident asserting that social reality–what we think of as “how the world works”–is the output of the following chaotic process.

nature (basically physics & biology) + nurture (operant conditioning) + randomness (error term)

I say this is a chaotic process because social reality is a three-body problem. There’s no closed-form solution. And the process is extremely sensitive to starting conditions. Everything else, as they say, is commentary.

I’m pretty sure the above is true. Yet it troubles me. First and foremost, it induces many a dark night of existential dread—that thick, dark curtain of despair that tends to descend whenever we contemplate our inevitable end. It’s not really physical death that bothers us (if it were, we wouldn’t find very much consolation in religion). No. What really bothers us is ego-death. What really bothers us is the dissolution of the self.

After all, physical death is no biggie if your consciousness (soul) transcends physical death. If that’s the case, then dying isn’t much different from moving to another country. Ego-death, on the other hand, is true death. Ego-death is non-existence. The void.

So what if there is no grand meaning to it all?

What if it all really does reduce down to nature + nurture + randomness, and the entire arc of the history of our universe is just a single run in some elaborate Monte Carlo simulation?

Frankly, you can take this to some pretty dark and nihilistic places. Perhaps no one articulates it better than the Misfit, the psychopathic antagonist of Flannery O’Connor’s short story, “A Good Man Is Hard To Find.”

“Jesus was the only One that ever raised the dead,” the Misfit continued, “and He shouldn’t have done it. He thrown everything off balance. If He did what He said, then it’s nothing for you to do but throw away everything and follow Him, and if He didn’t, then it’s nothing for you to do but enjoy the few minutes you got left the best way you can—by killing somebody or burning down his house or doing some other meanness to him. No pleasure but meanness,” he said and his voice had become almost a snarl.

The Misfit is one of my favorite antagonists in literature. You can read him almost any way you want. Maybe he’s nothing more than a rambling, murderous redneck. Or maybe he’s the most coldly rational, self-aware, introspective character in the story. The Misfit spent an awful lot of time in prison, after all. He’s had plenty of time to meditate on The Meaning of Life.

“Some fun!” exclaims his accomplice, Bobby Lee, after their gang finishes killing the Grandmother and her family.

“Shut up Bobby Lee,” the Misfit said. “It’s no real pleasure in life.”

(SPOILER) That’s the last line of the story. These days I like to read the Misfit as a kind of anti-zen monk. He’s got it all twisted. But he hasn’t necessarily got it wrong. He’s Hyakujo’s Fox. For clinging to absoluteness, he has been sentenced to suffer 500 rebirths as a psychotic spree killer.

So what the hell are we supposed to do about all this, exactly? How does one cultivate a clear-eyed view of our world without embracing murderous nihilism?

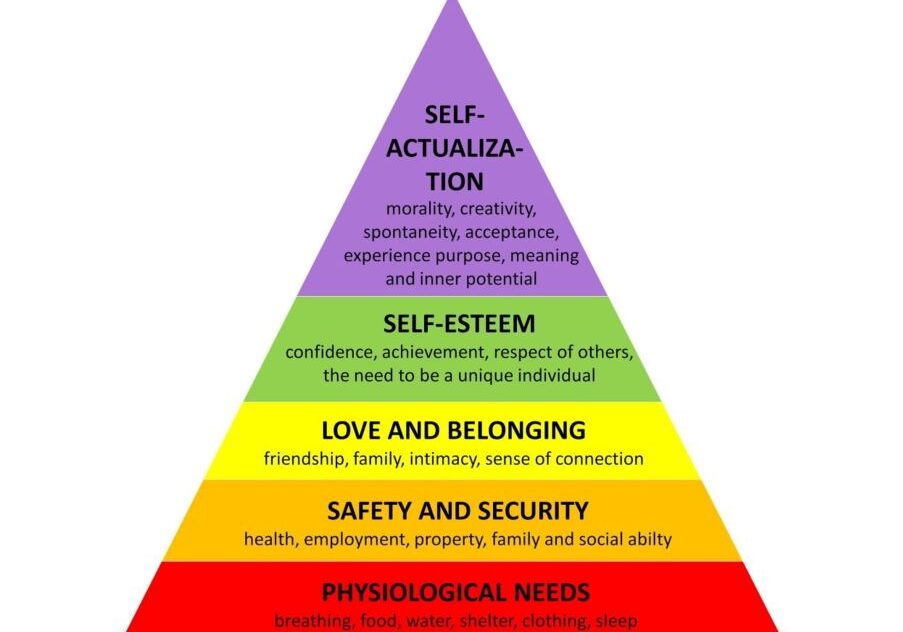

For starters, we quit looking for Answers. They don’t exist. Self-actualization has no closed-form solution.

But there is a Process.

The three images above are all of ensōs. An ensō is just a circle, drawn in a single stroke. Hitsuzendō is a form of zen practice where one draws ensōs as a meditative practice. The process is simplicity itself. You just draw a circle with a calligraphy brush. Maybe you close the circle. Maybe you don’t. Maybe you’ve got a thick, continuous circle. Maybe not. It doesn’t really matter what the circle looks like. Don’t overthink it. Just draw a circle.

Here’s the trick: everything we do in life and investing is as simple as drawing an ensō. Every. Single. Thing. As Ben wrote in his Clear Eyes, Full Hearts, Can’t Lose manifesto:

“You want freedom? You want an autonomy of mind and spirit? You want that as an inalienable right? A right that is yours simply because you are a human being? Well, that comes at a price. And the Kantian price is this: everything you do, you must do for the right reasons.

It’s really as simple – and as difficult – as that.

What are the right reasons? You don’t need me to tell you. You already know what they are, in every situation you’re in. You have a moral compass. But I’ll tell you anyway. Acting for the right reasons means acting in a way that reflects who you ARE as a moral human being. It means acting for your identity as a moral human being, not as a propitiation to some god or potentate, not as an exchange for some “greater good” that someone else has talked you into pursuing. Not even for gaining a Supreme Court seat. Not even for denying a Supreme Court seat.”

Note that I wrote this was simple above. I didn’t say it was going to be easy.

Question: Is morality socially constructed through a process where biological systems are socially conditioned to respond in particular ways to particular stimuli, or is morality an innate moral compass manifested in Kantian ethics?

Answer: Yes.

Now draw yours.

In the end, all you can really do is carry your cross to the finish line. Except there is no finish line, there is no cross, and there is no you.

Amen!

‘In the end, all you can really do is carry your cross to the finish line. Except there is no finish line, there is no cross, and there is no you.’

Nope! No finish line, no cross, and only you.