Dark Forest: The Brutal Game of Modern Banking

To learn more about Epsilon Theory and be notified when we release new content sign up here. You’ll receive an email every week and your information will never be shared with anyone else.

Continue the discussion at the Epsilon Theory Forum

86 more replies

The Latest From Epsilon Theory

This commentary is being provided to you as general information only and should not be taken as investment advice. The opinions expressed in these materials represent the personal views of the author(s). It is not investment research or a research recommendation, as it does not constitute substantive research or analysis. Any action that you take as a result of information contained in this document is ultimately your responsibility. Epsilon Theory will not accept liability for any loss or damage, including without limitation to any loss of profit, which may arise directly or indirectly from use of or reliance on such information. Consult your investment advisor before making any investment decisions. It must be noted, that no one can accurately predict the future of the market with certainty or guarantee future investment performance. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

Statements in this communication are forward-looking statements. The forward-looking statements and other views expressed herein are as of the date of this publication. Actual future results or occurrences may differ significantly from those anticipated in any forward-looking statements, and there is no guarantee that any predictions will come to pass. The views expressed herein are subject to change at any time, due to numerous market and other factors. Epsilon Theory disclaims any obligation to update publicly or revise any forward-looking statements or views expressed herein. This information is neither an offer to sell nor a solicitation of any offer to buy any securities. This commentary has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. Epsilon Theory recommends that investors independently evaluate particular investments and strategies, and encourages investors to seek the advice of a financial advisor. The appropriateness of a particular investment or strategy will depend on an investor’s individual circumstances and objectives.

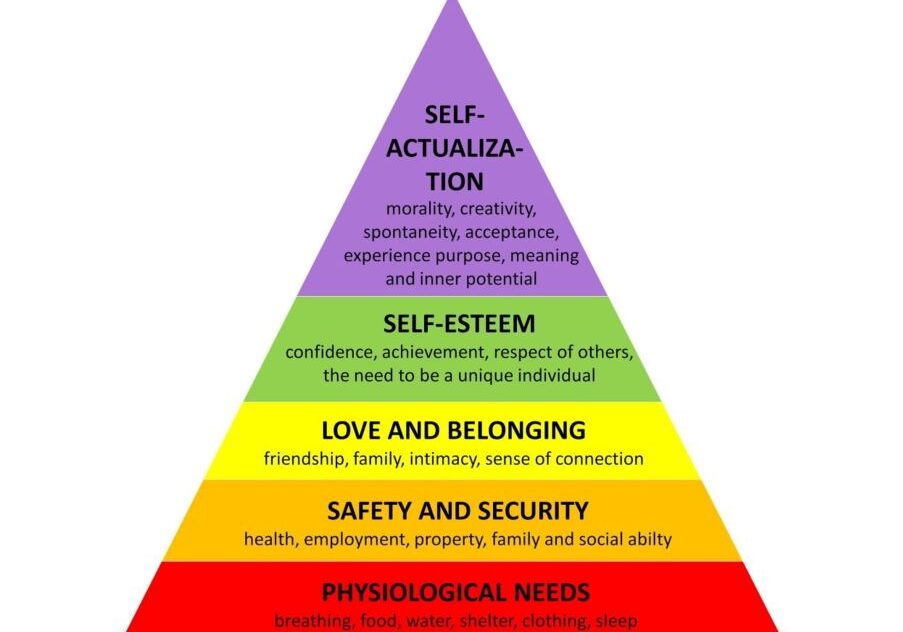

Thanks for the apt metaphor. Investors need to remember the adjectives of hunger and desperation translate into rising funding costs, falling net interest margins, tightening lending standards and greater credit losses for those on the outside looking at the SIFI’s. The fundamentals in the modern banking world are worse, and particularly in Europe this was a very crowded long trade. It was just reported that INFLOWS into the US bank regional ETF, KRE, were a record in the past week. The muscle memory of how to invest in a ZIRP world with endless backstops hasn’t changed…yet.

Love a good analogy. I enjoyed the read. Banks are suffering from what every business will suffer from eventually. Inflation created the need for interest rate hikes, and as cost structures adjust to the new inflation environment and new interest rates, all is fine as long as revenue grows in line with costs. But once pricing drops due to demand hits from fighting inflation, the lagging cost structure increases wallop the business. It already happened with used vehicles. Used car dealerships got slaughtered second half of last year because their costs (cost of inventory) adjust rapidly to the market. Automakers have a slower adjustment but are about to feel it. And banks had a surge in demand for deposits with stimulus money and did well on it, but now costs are rising but revenue is not (interest income). Every industry will have its turn, and earnings will eventually reflect it. The transition from inflation to not inflation is super damaging to businesses. What seems especially pernicious about banking is the counterparty risks between industry participants. Car dealers that go bust don’t have significant financial arrangements with other car dealers. That is where a really good analogy for the industry in real life is helpful. So, yes, the hunters with ample food are trying to lead, but how much food do those hunters have? And at what point do those hunters have to turn on the other hunters in the dark forest because the big hunters are worried about their food? I especially agree with your statement that the alternative of loosening monetary policy is just burning the forest down. The Fed knows it can’t reverse because inflation could get sticky and the Fed would lose control. Great stuff Ben.

The market is grappling with how confident to be in that statement. The Fed has its political mission of keeping an eye on inflation, employment, and financial stability. It’s behind the scenes purpose is to help the banking industry. Whether that is not raising interest rates for quarters after inflation took off, not actively supervising a technically insolvent bank that had outrageous deposit growth and inadequate risk controls, or possibly blinking on the inflation mission during a bank run.

I am not highly confident that the Fed statement and press conference messaging next Wednesday can fix all of these competing narratives at once.

Taking the analogy of the ‘Dark Forest’, Ben you express the hope that you see a way out of the American Dark Forest. However, what if in this interlinked world, the American Dark Forest is possible only part of the Dark Forest? Hunters / forces from other adjacent parts of the Dark Forest (Europe?), despite the measures taken, overwhelm the place with unfortunate outcomes?

Oh that’s the risk here, for sure! Just like it was for J Pierpont Morgan in 1907 when he tried to rally his peers to prevent a rolling series of bank runs. The difference today, and I think it’s a difference that makes all the difference, is that JP Morgan didn’t have a central bank to backstop the effort in 1907 and today they certainly do.

Don’t forget fighting climate change and promoting racial justice……

Can I fast forward to the end of the game and open up my bank account with Mother Nature?

Perfect analogy! Going a step further – doesn’t the question of whether cash deposits are safe for all depositors have to be answered? If only systemic banks are “protected” then the hungry hunters are carrying muskets instead of center-fire rifles.

Hahaha! The road to CBDC is paved with good intentions …

Yes, 100%. I’d favor insurance on all deposits up to $5m. Over that, you take counterparty risk with your bank.