Editor’s note: We’re pleased to publish a note today by Luis Perez-Breva, author of Innovating: A Doer’s Manifesto (MIT Press: 2017), and MIT Faculty Director of Innovation Teams Enterprise. Luis holds a Ph.D. in artificial intelligence from MIT, as well as degrees in chemical engineering, physics and business. He is an inventor and entrepreneur. He is also, as of a few weeks ago, a brand new American citizen. If you’d like to connect with Luis, you can find him on Twitter at @lpbreva or via email at [email protected].

As with all articles we publish from our guest authors, this note may not represent the views of Epsilon Theory or Second Foundation Partners, and should not be construed as advice to purchase or sell any security.

We may have perfected the wrong economy; we’ve got one that struggles to protect the long-term survival of the species. But we can fix that.

We can move past Speculate-ship, allow ourselves to do well and good at the same time, and put energy into building a Society of Tinkerers … with just enough good ol’ American ingenuity to invent our way to an economy in which greed is once again aligned with survival.

Ok. There are some new terms in there. To explain, let me start at the beginning.

Whether it’s this pandemic, or inequality, or the opioid crisis, or climate change, or whatever comes next, the most important crises hit us when we’re almost ready to handle them. And it’s almost always the same big, invisible enemy: humans — who are (unknowingly?) laying waste to our own species.

As is often the case in these almost-ready moments, everyone’s in denial—just like we’re now talking about getting back to some “normal.” Sigh. Fast forward. I propose we seize the moment to make it harder, less fun, and definitely less rewarding for humans to bring the species down and with it the economy every time someone sneezes the wrong way.

There’s got to be a way to help humans help humans that’s compatible with making money, or we’re doomed.

Herein lies our chance to establish a different enterprising mindset.

- We need new ways to explore problems that matter.

- We need to share hands-on knowledge with society so that anyone who wants to tinker with problems can tinker with problems.

- We need an alternative to the zero-sum speculation that poses as celebration of entrepreneurship.

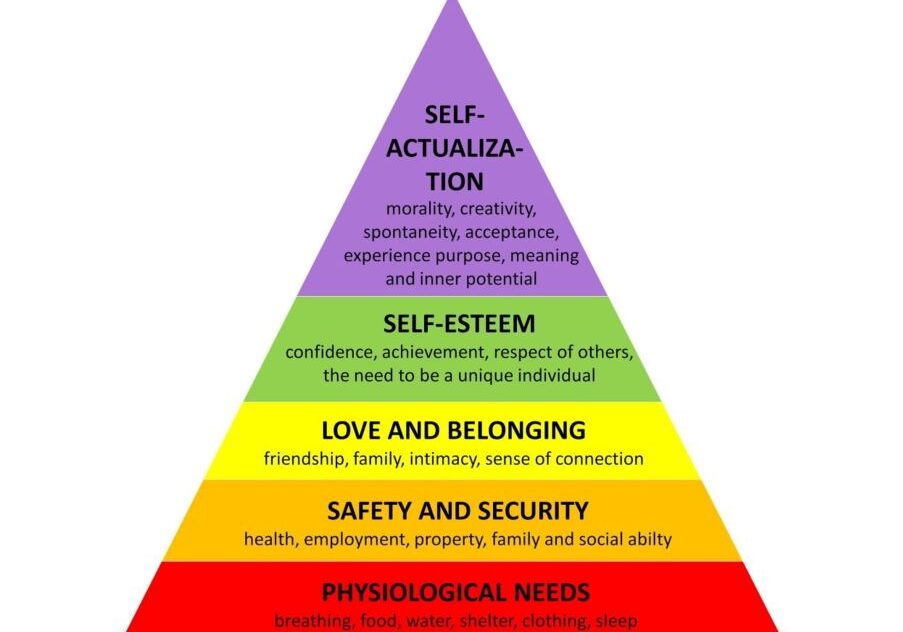

Letting go of speculate-ship and daring to create a Society of Tinkerers is not for the faint of heart. It’s about appreciating how true wealth, the idea of wealth itself, ought to be sustainable (you could ask Marie Antoinette what will happen to your wealth if we reach a point at which no one can afford anything).

But to thrive in this new mindset we may need to accept that we face a tremendous deficit of authenticity in investment, entrepreneurship, leadership, and generally education that has resulted in a genuine surplus of frivolity and waste.

These crises are so moronically “elitist” (epidemiology, climatology, socioeconomics) that it seems as if you need some kind of advanced degree just to read through the gobbledygook, let alone have any real understanding about what’s truly going on. We need to stop creating opportunities for any random idiot to call everything “fake news” and appear more believable than current events only because his/her stupidities can be understood and current events can’t.

We all hope entrepreneurs will get us out of this. After all, “Entrepreneurship” has been touted as the greatest invention of the late twentieth century. Along with the culture of “startups” it spawned, it was supposed to help us continually reinvent our economy for the better. Instead, beginning in the 1980s, we fell into a pattern of chasing after “solutions” to whatever next big emergency, bubble, or crisis comes along — and getting nowhere.

So here we are. The distraction of seemingly easy money got in the way of doing things that matter. It made us complacent. Bad slogans emerged in the entrepreneurship world: “Fail fast!” and “Pay it forward!” We accepted as just fine that 9 of 10 startups fail: “It’s okay! Here’s your participation trophy!”

That’s right: every year in the United States, we expend about $75 billion to back new venture formation, with odds of success hovering around 1 in 10. That’s quite a “death rate.”

By the way, every year nearly five times as much goes to philanthropy.

Hence, frivolous and wasteful. We grew content with mediocrity, inclined to rush the next “great” idea out the door — lately, that’s likely to be some app that spies on you. Not surprisingly, from the need to track a virus everyone came up with a “solution” to lapse into spying on people’s interactions—as the New York Times has reported.

The fact that so many thought this — the very essence of speculate-ship — could ever work reveals far too many of the defects in our thinking. Just as the “Spanish Inquisition” became the theme of the late Middle Ages’ resistance to any kind of science, the theme for our era’s resistance to addressing problems that truly matter could be: “Everything can be solved by ‘spying’ and ‘running ads’.” And so, the past two-plus decades may be remembered for crashes, deepening inequality, and putting humans on the verge of extinction.

Does anyone really believe that this kind of “entrepreneurship” can get us out of our current crisis? What good is the next “killer spy app” when a virus can close entire countries, climate can force refugee crises, and inequality drives opioid epidemics? At the other end of this pandemic may lie a veritable wasteland full of newly dead companies that will join the already huge pile of bad startup ideas, wasted “innovations,” and failed venture funds. What if this were salvageable?

Given the dismal success rate of venture investing and an obvious desire in America to put money into worthy causes, I can’t help but wonder why we separate the two. The short answer is “the tax code.” But the longer answer may be more telling, as the well-known investment advisor David Salem once pointed out to me: It’s the “cheap capital.” When capital is cheap, wasting money is less expensive than thinking through a long-term way out of a mess.

That’s why I wonder whether we perfected the wrong economy. What if we could resolve these contradictions and unite these forces — do good and do well — in a new way? What if we could reinvigorate American ingenuity while creating breathing room for a kind of entrepreneurship intent on solving problems that matter and building great companies rather than just selling startups?

About a year-and-a-half ago, I gave a talk to the Harvard Business School Entrepreneurship Club. I was asked: “How do I find an idea, even ONE to invest in?”. At the time, with daily articles about the opioid epidemic, weekly climate protests, and monthly articles detailing the rise of income inequality I sought to inspire these wannabe entrepreneurs to do something that truly matters.

That seems especially relevant today — and perhaps even easier to explain. There are now at least three ways to play “entrepreneur,” but not all lead to the economic progress we now need. I call them: industrialist or businessperson (let’s call it Entrepreneur 1.0); Speculate-ship, as I mentioned at the beginning; and Tinkerer—the newest one and the basis for the society of tinkerers. Tinkerer is only now emerging. It longs for entrepreneurship with meaning. It fulfills our ambition for wealth that is sustainable. It is the one I’m set to help prosper. But for me to explain why, I need to make sure we are all on the same page about the other options.

The likes of Henry Ford, Nikola Tesla, Thomas Edison, and other industrialists inspired an Entrepreneur 1.0 culture that includes today nearly everyone who dares launch a business—a technology company, restaurant, consulting firm, law firm, or whatever—or who evolves a work of art, movie, or book into a business.

The key characteristic these Entrepreneur 1.0 people share is that they are driven to work on something they are curious about, care about doing, or think they are good at. Extreme Entrepreneur 1.0 people are further defined by a problem they have an itch to solve — typically a problem that looks intractable to others. Even just working on the problem seems preposterous. Those who solve such problems are judged along the way by their idiosyncrasies and later revered for their successes. The Elon Musk who set out to ship a greenhouse to Mars and who ultimately founded a private company, SpaceX, that managed to take astronauts to the space station in the middle of the 2020 pandemic, falls in that category.

Entrepreneur 1.0-built organizations were built to last. Alnylam, Square, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, as well as older examples such as Bloomberg, Hewlett-Packard, Intel, Apple, Oracle, Microsoft, Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway are all examples of the Entrepreneur 1.0 way—that is, starting a business without one of the trendy recipes, and keeping at it.

Today there are still great examples of individuals set on the ways of Entrepreneur 1.0: Leila Phirajhi of Revivemed; Mariana Matus of BioBot analytics; Harry Schechter of the IoT company TempAlert; Ferran Adrià, the Spanish chef; Alexandra Wright-Gladstein of Ayar Labs; David Brewster and Tim Healy of EnerNOC; the investment strategist and founder of Epsilon Theory Ben Hunt; and many others. Investors that go beyond simply speculating with startups and put their money and savvy at the service of problems worth solving fit the profile, too: Khosla Ventures’ Vinod Khosla; Noubar Afeyan of Flagship Pioneering; and DFJ’s John Fischer. They can all be Googled.

If you accept that the business of Entrepreneur 1.0 can truly be anything, it becomes possible to view the Star Wars or Harry Potter franchises, too, as examples, and find inspiration in the work of George Lucas, J.K. Rowling, will.i.am of the Black Eyed Peas, and countless others that started with a passion and grew a successful business out of it.

If you’re wondering why I had to say any of this at Harvard, then you may not be aware that elite universities have taken to popularizing another form of “entrepreneurship” over the last two decades. Because of that, the stories of Entrepreneur 1.0 rarely make it to entrepreneurship classes these days; they just don’t fit well with Speculate-ship—that is, the “pitch a minimum viable product” formulation and run with it that is all the rage.

Most prevalent in the past few decades has been doing a startup — or more accurately Speculate-ship.

The goal: found a startup born to be sold — and exit before it exits you.

Speculate-ship is fueled by Lean Startup, Design Thinking, the 24 steps of Disciplined Entrepreneurship, and the Startup Owner’s Manual. It’s driven by evocative buzzwords (shown here in italics): have a product or service idea; talk to lots of relevant people to validate it; give the high growth speech; do some inexpensive experimentation about the features of a single would-be product of a single-product startup; and measure success by number of users, not dollars. If it doesn’t work out, start again with a new idea for a new product. A 2019 series of articles in the Economist magazine provided a litany of reasons for why the unicorn craze that follows Speculate-ship looks more like a scam than anything entrepreneurs should pursue.

Sure, Speculate-ship has worked well for some. But here we are, immersed in at least three deep crises, without any of these “ready-made” solutions to pitch as consumer products.

Back to the question Harvard students asked: “How do I find an idea?” It’s not really about “wealth” or “speed” — all approaches could lead to wealth, and speed is tremendously variable. Snap and Tesla Motors both went public about seven years after they were founded — the software startup required five times more investment than the car manufacturer.

The way to choose is to determine how you want to play it out. And that needs serious thinking today. Entrepreneur 1.0 is about building an organization; it means you have to play the game of scale, which means you need to use and invent technology (that’s what technology is actually for: to achieve more). Speculate-ship is about fundraising for a product, about getting investors; the game you play is one of perception, and for that you’ll need messaging.

But what about the crises we face today? What about the doing good and doing well option? That’s the path I’ve called Tinkerer. It’s only just beginning to reveal itself fully as a possibility now that frivolity and waste can no longer be an option. It can take us out of this vicious cycle of crises. It’s our future.

The people along this path are industrious and learn by doing. Tinkerers learn to home in on problems with intense practical experience, wielding technologies and knowledge of any kind —engineering, sciences, but also liberal arts, finance, whatever — to gain true insight. It is not about following recipes or doing startups, but solving true problems — the kind we don’t yet know how to solve. This talent grew in an economy that’s no longer defined by lifestyle jobs, as Sarah Kessler explains in her book Gigged, but could be defined by problems solved. These tinkerers seem able to hold on to the belief they can do well and good even after being told otherwise throughout their schooling. This new talent redefines what it can mean to be one’s own boss.

Tinkering comes first, before an idea gels. That’s how Thomas Edison worked. Tinkering precedes without expending even one iota of energy on developing the perfect pitch for investors or even deciding to start a company. It keeps one from rushing before an idea is really sound.

The tinkering I’m talking about is often predicated on simple yet seemingly incongruous premises. For example: What if there was a way to align greed with the saving the environment — the greedier you get, the more habitable the planet? Or: What if we brought back manufacturing, with new, good jobs, by decentralizing factories to outperform the ones that went overseas? Or: What if we could recycle all the innovation waste and put technologies that were left on the shelf in the hands of anyone who wants to tinker with them?

In fact, these are some of the hunches for new problem-solving organizations we’ve already begun to work on. So many of the enterprises we celebrate today began with touches of lunacy just like these. You can find some stories of these kinds of ideas in my book Innovating and Safi Bahcall’s Loonshots.

I’ve spent the better part of a decade training and guiding people who wanted to be involved in innovating and learning to use any technology (not just apps) to tackle real problems. I’ve witnessed the emergence of a growing number of talented industrious people who long for means to solve —sustainably, and at a profit — the most-challenging real-world problems that matter but that are going largely unaddressed. These are the new Tinkerers. To tackle the problems traditional approaches to venture finance or philanthropy have put out of reach, these new professionals are in need of a community, instruments, a method, and jobs in which to deploy their talents for problem solving.

This moment calls for exceptional talent and capital ready to embrace a simple principle: there’s more good and money to be made investing in organizations engaged in continually solving problems that matter than there is in splitting hairs over 9 in 10 odds of failure and scheming about who might be left that can be persuaded unicorns exist.

We don’t need more minimally viable products.

We need more maximally viable organizations attacking big problems with a tinkerer’s mindset and a capitalist’s goals.

In the face of the coronavirus pandemic and the changed world we will confront when it’s over, I’m feeling an intense urgency to help build that community in which Tinkerer 1.0 people and a new kind of forward-thinking investor can thrive.

I envision a new kind of investment and development firm set on exploring problems that matter, building bold organizations that fail to fail, recycling insights and technologies to arrest the innovation waste, and making instruments for problem-solving broadly available to propel a Society of Tinkerers committed to addressing problems that matter.

That’s the reimagination of development we need to get past this era of setting off crises and venture into the uncharted land of doing good and doing well that traditional venture and philanthropic thinking have so often put out of reach. These seem like the right next steps to make innovation “grassroots” again, super-powered by the American ingenuity still out there and waiting to be tapped, and thus restore the connection between work and economic progress for individuals and for the nation as a whole.

I like the idea of incentivizing companies to publish their unused R&D. A suggestion on how to make that happen:

Make it so that, while companies can still deduct the value of R&D efforts, if they are not using the results of their R&D in a commercial effort within a few (eg: three) years, they must either release those efforts into the public domain or risk the government clawing back the associated deductions.

Not sure what the accounting changes will be needed to keep track of which ideas are associated with which deductions, and what exactly counts as being used in a commercial effort.

Some way of tying the deductions from R&D to actually using them I think makes sense though. We allow deductions because, in lue of the tax payments, the research benefits society, however it stops doing that when it just collects dust on a shelf.

Very nice piece overall, thank you for sharing your thoughts here Luis.

Peter Drucker was famously said, “The purpose of any business is to create customers.“ I am in the railroad business and it appears that the big names in the sector are doing more to run off customers then to create new ones. Wall Street has glommed onto the themes of “operating ratio“ and “precision schedule railroading,”

yet rather than using these themes to create new customers and build franchises with older customers, managements are using these tools as an excuse to cut costs, thereby improving the operating ratio without improving the core business.

Happily, there is a cadre of smaller railroad operators who have glommed onto the entrepreneurship 1.0 theme. That’s where we’re seeing the growth; that’s where we’re seeing more customers coming to the railroad than running away from it.

The present “financialization“ model of increasing earnings per share by cutting costs and buying back shares isn’t doing the customer any good. The chief beneficiaries are the executives with their stock options and – for the moment – shareholders who are buying the OR/PSR/share buyback program story.” The employees, the suppliers, and the customers see no benefit whatsoever and are increasingly looking away.

Time to bring on entrepreneurship 1.0 on a larger scale to benefit all stakeholders.

My biggest takeaway: “so moronically “elitist” (epidemiology, climatology, socioeconomics) that it seems as if you need some kind of advanced degree”… this is the biggest problem to solve of our multi-silo world, aka how to enable things to be done by a five year old

Thanks for posting Luis. For some reason, your article reminded me of Andrew Higgins and the Higgins Boat. I suspect he might fit your description of tinkerer:

Andrew Higgins, a fire-tempered Irishman who drank whiskey like a fish, was originally building oil-prospecting wooden boats in Louisiana. Once WW2 broke out, he was positive there would be a need among the U.S. Navy for thousands of small boats—and was also sure that steel would be in short supply. In a common moment of eccentricity, Higgins bought the entire 1939 crop of mahogany from the Philippines and stored it on his own. Higgins’ expectations were right, and as the war progressed he applied for a position in Naval design. Insisting that the Navy “doesn’t know one damn thing about small boats,” Higgins struggled for years to convince them of the need for small wooden boats. Finally he signed the contract to develop his LCVP.

https://cs.stanford.edu/people/eroberts/courses/ww2/projects/fighting-vehicles/higgins-boat.htm

Best regards,

Otto Lowe

Dr Perez-Breva, thank you for this timely and timeless post, and congratulations on becoming a US citizen!

I say “timeless” because the battle to encourage innovative thinking and problem solving has been around for decades. As long as there is more money for “integrated systems” programs rather than IRAD (independent R&D), publically held engineering companies will tend toward rewarding “grinding” over tinkering. There’s a fine line between the two, with the tinkering mindset being the one that is most likely to get punished if deadlines for deliverables are valued over investigation. An obvious example (to me anyways) is the contrast between achievements of the Apollo space program v. the decisions that lead to the Challenger space shuttle disaster.

On a smaller scale, some of the more successful engineers I’ve known stubbornly stuck with their ideas and either left a company or even dropped out of school. They had the strength of personality to persist and finally convince others to either join them or at least buy into their good idea. That’s the hard part to teach: knowing when is the right time to quit and take one’s grinding/tinkering ability someplace else to start something new.

O.P.A that’s a fair point, and with the right set of incentives (e.g. R&D deductions) I can see how it would help make the case for more sharing to companies with R&D .

Once convinced that some degree of sharing (vs collecting dust) is advantageous, demonstrability of use would be key. One of the things that we would need is a clear way to demonstrate the R&D is actually being used. That’s one of the aspects of intellectual and industrial property that is most baffling. So I think we need a way to help R&D-heavy companies demonstrate that, and that’s a business question too.

I imagine a new kind of instrumentation company intent on turning that R&D into a tinkering instrument. The kind of instrument that helps tinkerers explore problems. That way R&D producing companies could readily demonstrate their R&D --the same that would have previously been doomed to shelves-- is now being put to use for exploration. To R&D companies this could look a lot like taking an insurance while at the same time de-risking their R&D.

Accounting and taxes are not my areas of expertise, but I’m intrigued by your comment. Do you have a sense for how many changes would be required to tax codes and accounting to enact your idea?

Zero Mugen, that’s quite right and I believe we need to help more people see the connection the way you brought it up: our ridiculous approach to silo knowledge is causing false elites and much mistrust.

Economists tend to praise specialization and they have a point, but the hyper-silo-ed world we’ve created has taken that to a dramatic extreme. So much so, that at times disciplines seem to exist for the sole purpose of excluding others, that is, create “elites”. Come think of it people think about patents much the same way “to exclude others”. The Founding Fathers had loftier goals when they elevated intellectual property to become a constitutional matter “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

We oughta expect more. I believe those two problems are related, I think we are in sore need of a new literacy effort. I think tinkering is as critical to that effort as the ability to dabble in words was to the first effort to increase literacy.

Interestingly, universal access to education led the charge over a hundred years ago; now silo-ed education and the creation of elites might have become the problem. Rusty Guinn has few great pieces here on Epsilon Theory on the topic of higher education.

P.S.: BTW, five year olds, really? well, that might be just a tad too young, but I taught my 10 year old daughter (now eleven) differential calculus reading together the book “Measurement” by Paul Lockhart. So believe me, we can do far better than we are doing. Incidentally, next up for us is finding good books to read together on Quantum Mechanics and Game Theory, … Ben any ideas?

There’s a big problem with democratizing innovation in the context of building sustainable businesses, and it’s the inevitable knock-off product. Not enough people are talking about how this is gutting small business innovators. Why bother making a new product when it will be copied and sold for less?

The commercial trajectory of consumer 3D printing is a useful lesson. Patents locked up 3D printing cost/availability for a couple decades, and it was priced out of consumer reach. Then around 2010 open source advocates (tinkerers) in the RepRap movement and early community-oriented 3D printer manufacturers created innovative, important products that destroyed the Stratasys / 3D Systems patent duopoly, and made all the key enabling IP public (out of the exact ethos that I think Luis is advocating here). Both hobbyist and commercial R&D outputs were aggressively shared via open source software and hardware designs. Development was rapid through 2010-2015 and we saw a big hype-cycle boom. Unfortunately, the open source development also gave away the keys to the kingdom. Once the technology and market were proven by primarily US and EU inventors, the public IP got picked up by Chinese manufacturers with lower cost structure and no R&D costs, and most of the 3D printing innovators were commercially obliterated. Desktop 3D printers are now mostly commoditized, and innovation has greatly slowed in the last few years. There are pros and cons to this; consumers do get much cheap 3D printers now…

The key point is, if you invent a consumer product today that doesn’t have some difficult-to-copy “secret sauce” or enforceable legal protection preventing knock-offs, it will be cloned and sold on Amazon at half price by five no-name competitors before you have a chance to scale. End of story. This is every consumer device now. International IP legal enforcement is only affordable for major corporations, so your choices as a small business are basically secret sauce or death. We’re now seeing the end of the line for traditional “guy in a garage” Entrepreneurship 1.0 business development. You need secret sauce to compete.

Put another way, the way you make a successful business today is by getting enough of a head-start to scale before being copied. What works today as secret sauce? A large body of compiled code. Deep private databases. A large body of quality user-generated content. A service-oriented user experience. A big pile of VC money in a field with high barriers to entry. Regulatory protection. Working in an obscure B2B sector that Chinese businesses don’t have visibility of. Working in a quality-critical sector that doesn’t want to buy Chinese products.

So, it’s unsurprising that most startups today are data-mining apps. It’s a reliable source of secret sauce. If you want to fix entrepreneurship, you have to solve the knock-off problem.

Hi RCarlyle, good points.

I believe I’m proposing a different kind of fix to what you call the “knock-off” problem. This may be hard for some to read, but the companies (new or old) that will get us out of this mess are not the one leading to things that are so easy to knock off. To your point, with so many no-name companies knocking off stuff left and right, if that entrepreneurship with its knock off problems were the solution, we’d be all set: Those knock-off manufacturers would have solved it.

A more genuine approach to problem-solving is bound to attract long term investors, philanthropists, and sustainable investors too. My experience educating talent at MIT and worldwide on how to address problems that matter by doing allows me to be hopeful. But as I say in the article this is a new profession altogether not to be confused with speculateship.

BTW, you may find it interesting to read Marina Hatsopolous (founder of Z-corp and 3D printing business pioneer) retelling of the story of 3D printing and how she as CEO led the company to compete with 19 other companies that were given non-exclusive rights to MIT’s portfolio of 3D printing patents in the early 90s.

Thank you Chipperoo.

I too believe the incentives are stacked up against the kind of tinkering, or at least have been as of late.

What my (privileged) position at MIT has given me a chance to observe is that the numbers of tinkerers are growing. Sure, everyone expects engineers to be drawn toward tinkering, so few might be surprised by stories of engineers that tinker and persists as you well put it. But what made me realize tides may be changing for the better is that finance students too were asking for the opportunity and the education to learn to use their skills to find new and better ways to help and solve problems. Maybe the era of the startup for the sake doing a startup is finally over.

So we have the people to do it and the appetite to do it. I am convinced we can bring long term capital to help us change the incentives.